Retrospective Resonance on Listen Deep: Poetry, Sound and Multitudinous Remix

March 8, 2021

Klara du Plessis, Deanna Fong

Whenever Goethe spoke, his voice produced vibrations…These vibrations encounter obstacles and are reflected, resulting in a to and fro which becomes weaker in the passage of time but which does not actually cease. So the vibrations produced by Goethe are still in existence…

—Salomo Friedlaender, “Goethe Speaks into the Gramophone” (1917)

—

Two years ago today, we participated in the event Listen Deep: Poetry, Sound and Multitudinous Remix, curated by Margaret Christakos and hosted at the University of Toronto on 8 March 2019. What follows is a brief description of the event’s activities, and then a transcription of a conversation that we had shortly after the event. We met at the Hinnawi Bros. Bagel Café across from Concordia’s Hall Building (hard to imagine a work date at a coffee shop these days), and discussed our immediate reflections on the day. Playing with Friedlaender’s idea that all spoken words remain in the world as vibrations that are imperceptible to the human ear—vibrations that can be picked up and made audible with the right imaginary amplification device—we wish to discover what other frequencies our past spoken words might tune us into. If you attended and/or participated in the event, we invite you to add your thoughts, memories, and reflections to a Google Doc version of this post using the “insert comment” feature; these comments will be transcribed and added as footnotes to this post on SWB (please let us know if you would like to be named or remain anonymous in your comment). We hope to continue the practices of listening and responding initiated in the original event in this written medium—that is, at least until our voices can sound together again.

—

Listen Deep was a three-part event. The first part was a workshop led by Anne Bourne, a certified instructor from Pauline Oliveros’ Deep Listening Institute. Approximately 30 participants stood in a circle and did a series of listening and responsive vocalization exercises. These started off as non-verbal, focusing on tone and vowel sound, then moved towards verbal communication. It was an extremely meditative sonic practice, which informed the experience of the rest of the day.

The second part of the event was called Rotary Poetry and included six poets: Oana Avasilichioaei, Canisia Lubrin, Donia Mounsef, Sachiko Murakami, Charlie Petch, and Moez Surani. There were six poets, four locations, and three sessions, and audience members could choose three consecutive events they wanted to attend. So both the poets and the audience members were rotating among the four different rooms and the three different time slots. Klara attended events by Oana, Moez, and Sachiko, and Deanna attended events by Charlie Petch, Oana, and Sachiko. Each time slot was 40 minutes long, meaning that each poet could create an immersive experience of their work, veering off from straightforward reading and creating performance art or more multimedia performances.

The third and final part of the event was the Library Plenary Sounding Party (referred to in our conversation as the Library Plenary Reading). During the Rotary Poetry, participants were instructed to participate in a remix project by writing down snippets of sounds/language that stood on little coloured strips of paper. Six students collected all the slips of paper at the end and did a remix of each poet’s work that they then read at the Library Plenary. This was followed by short readings from the six poets who participated during the day, with the exception of Canisia. The evening concluded with a collaborative group reading of Margaret’s work, which included Klara and Deanna in its members.

—

[Background chatter at Bagel Café]

Klara du Plessis: Part of my preliminary doctoral research is the idea of curatorial agency: the curator’s conscious intention for a literary event and how she applies organizational decisions to structure and produce a dynamic experience of that event. I was fascinated by the framework that Margaret Christakos created for Listen Deep, a structure within which things could happen organically. I asked her about it at the Plenary Reading and she said that she didn’t actually know what people were going to perform. So, while she chose the poets, designed a highly constructed day–leading strategically from one event to the next–and created the overarching intention of deep listening (which informed the way that the day was experienced by the audience), she didn’t actually know what the poets were going to perform. One could argue that she’s dividing the event between the highly curated and the improvisational.

Deanna Fong: Almost like making an event score. Which is very different from the event curation that you do, for example, in Deep Curation, which is an intervention on the level of the text rather than the event.

KdP: Talking of scores, I attended Oana’s first performance, “Operator,” which is an iteration of surveillance work that appears in her new book Eight Track [at the time of this conversation the collection hadn’t been released yet]. It was a combination of her own pre-recorded voice, found material from military drone strikes, the projection of a visual component, and her live performance, creating tactile, sonic effects by crumpling paper over microphones, using a brush to sound like rippling sand, and so on. During the question and answer period after her performance at Listen Deep, she used the word “script” too and she talked about her work being both scripted and improvisational. For me, this mode of creative production is aligned with what Margaret was doing with the day as a whole.

DF: Do you think there was something in the Rotary Poetry structure itself which lends itself to a certain improvisational nature? It is actually quite unusual to have mobile poets and mobile audiences, after all. Was it different from the Library Plenary reading, for example, which maintained a more traditional format?

KdP: Just the fact that the Rotary Reading sessions were 40 minutes long meant that the poets could really do something special during that time. A series like the Sir George Williams reading series in the 1960s included poetry readings which were substantial in duration, but these days it’s fairly uncommon for poets to have that much time during a poetry reading, unless they’re the keynote speaker or their career is very established. Most poetry readings are 10 to 15 minutes long. So having 40 minutes at their disposal, the poets definitely had to be more intentional about how they were going to divide their time, to design work which would fit the format.

DF: I felt too that, because there were probably only 40 of us audience members in total at that portion of the event—so maybe somewhere between 6 and 10 audience members per session—the intimacy of that really lent itself to a different kind of performance where the poet was perhaps a little bit more engaged with the audience. Especially seeing Charlie Petch because they were performing a vaudeville piece and coming up and gesturing to specific audience members or almost touching a shoulder, so it was a very theatrical performance. But I think the intimacy of the space really lent itself to that gesture.

KdP: Did you see Moez’s work?

DF: I did not, I really wish I did.

KdP: Talking of intimacy, Moez has a project called “Happiness,” which is apparently just a list of the phone numbers of his closest friends. As an offshoot of this project, he phoned two of his friends during his two 40-minute readings and just chatted with them about happiness. The audience was voyeuristically implicated and, as the event continued, started interjecting comments and asking questions. This is an example of an event that is almost more like performance art, again, both scripted and improvisational. The intimacy of sharing a conversation with a close friend, putting that person on the spot and making that conversation public, is huge. Moreover, Moez intended to keep his friends’ identities anonymous, but during both performances he accidentally gave them away; during the first conversation he named the person and in the second one the audience could see the screen of his phone. So the performances ended up being even more intimate than he intended.

DF: I do want to have a conversation about what role the space played in structuring things, how we listened to things, how we received things, our perception of things and how it just sort of had a role, an agency in shaping the event itself. I don’t know how that conversation piece would have worked in that giant library space.

KdP: Oh yeah, Moez’s piece was already barely audible.

DF: How many people do you think there were in the plenary, 50?

KdP: At least.

DF: So the classroom setting is the ideal venue for Moez’s improvisational work. However, there are so many elements of the Library Reading that really played with the expansive acoustics of that space.

Margaret Christakos at the microphone and amid the carrels at the University College Library. Photo by Klara du Plessis.

KdP: The Library Plenary Reading really used its space well because there were all these carrels which created barriers for sound and vision. For example, there were a number of musical performances and the sound would emanate mysteriously from unseen musicians behind the carrels. There was also a student-run comic skit, which maximized the fact that the audience couldn’t see them behind the carrels, but could hear them. Slowly, the audience pieced together the aural effects, becoming increasingly conscious of the fact that what they were hearing was intentional and not accidental.

DF: And really playing off of the symbolic meaning of the space—the library—because it was all these transgressive things that you’re not supposed to do in a library like take a phone call, eat a snack. So it got bigger and more and more absurd. Actually it made me feel really anxious. I’m really sensitive to my auditory space in public, so I had interesting feelings relating to the space, in an acoustic sense. I don’t think I was the only one either.

KdP: During the Rotary Readings, Sachiko Murakami’s performance was the closest in form to a traditional poetry reading. Did you attend any other sessions that focused on the act of reading?

DF: Sachiko’s was more structured like a standard poetry reading, but there were these fugitive moments of improvisation too. The whole book is talking about the sensation of presence—she read from Get Me Out Of Here—so especially the ways in which the space of the airport creates anxiety. So when she was reading from it there’s a poem in which it just talks about looking around the space, so the speaker of the poem is talking about looking around the airport, but instead she transposed that to looking around the space in the room, so she looked around and said, “Ryan,” who was sitting next to me, “projector,” “window.”

KdP: It made us all aware of our own presence in the space.

DF: So I wanted to ask you, one of the things I came away with that day was a very strong sense of physical grounding and embodiment. I think that really stemmed from attending Anne’s workshop. One of the strange sensations I noticed from that component of the event was that the hour went by as if it were only a matter of minutes. I think it’s very rare that we’re so attuned to what we’re doing with our bodies that it actually just takes on its own time. So I’m wondering whether you had any embodied sensations?

KdP: Definitely. I can answer your question in a few different ways. First, I was extremely aware of the difference between sound and language, sounds and words, during that practice. Anne started with having us chant and working with vowel sounds which were more abstract and non-linguistic, and then, because the majority of people in the room were writers, proceeded to start using language. Personally, I felt way more connected to everyone in the moments when we started using language. I started feeling more comfortable, less anxious and able to really experience the fact that we were all there together; language allowed me to access the interconnectivity that she was trying to create between us, the literal energy chains she was trying to create. That was one very curious moment for me. Why do writers, or why did I, become so verbally attuned that communicating through sound becomes a cutting off?

Recently, I was reading parts of Fredric Jameson’s Antinomies of Realism, and here he posits a distinction between emotion and affect, the former being this extremely name-oriented expression of feeling—anger, happiness, and so on—while the latter transcends synthesis in language, using intricate realist description to gesture towards a sensory experience without labelling it. In terms of the practice we did with Anne, it’s interesting to consider how extremely semantically attuned we become as writers to the extent that the affective, non-linguistic field of sonic practice alienated a lot of us and we almost needed the more directly emotive words in order to connect and be present together.

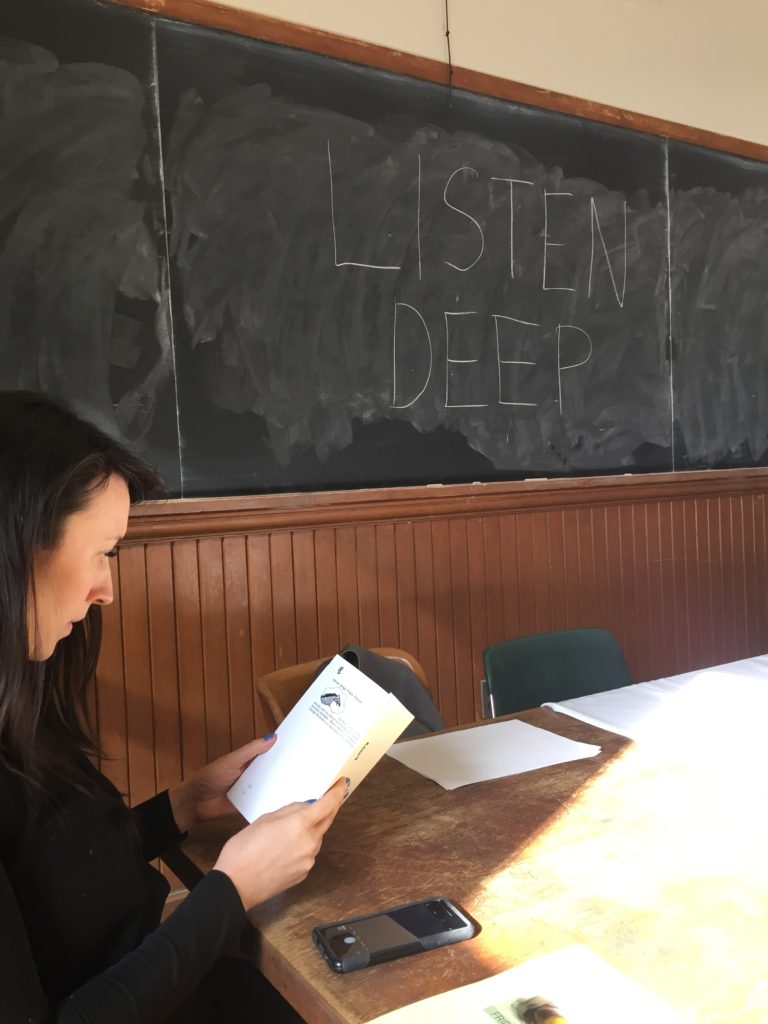

But to return to your question about the space, the second answer I would give is the space itself, the entire University College building, which is a beautiful, older piece of architecture with lots of intricate woodwork and incredible windows. Most of the events were suffused in amazing afternoon light. The building was also on the more decrepit side with lots of peeling paint and the woodwork could do with some love. The space romanticized the day for me. Being in that space felt so outside of my normal reality that I felt somehow more present and more included.1 Although I should reiterate that this sense of groundedness might go back to the initial meditation practice with Anne, I do think the space added to my level of concentration and consciousness.

How were you experiencing it?

DF: Well, I think maybe very differently. One was that I found initially a really hard time of getting into the mindset that I was listening at all, because I was so self-conscious of the fact of being listened to and being observed.

KdP: You mean in the initial practice?

DF: Kind of throughout. Because I think when we make sound and language the object of contemplation itself, for me there is a tendency to feel a bit apprehensive about that. As bpNichol says in his Four Horsemen essay, we’re really afraid of dangerous sounds, especially nonverbal sound, because it is so rare that we use it and usually when we do use it it’s in moments of crisis when language is not an option for expressing what you actually mean. And so, it feels really uncomfortable to just be making a bunch of sounds in front of a group of strangers. We didn’t have an introduction to one another before we started doing this intimate, collaborative practice, so I found myself doing a lot of self-monitoring and not doing a lot of listening for the first little while. But then once I stopped focusing so much on what I was doing in terms of producing sound and listening a lot more, which is the point of the exercise in the first place, then things really opened up for me. And by the end I was able to achieve a sense of balance between playing with producing and responding to sound, and merely being receptive to it. But it took me a long time to get there.

KdP: Well, there was a moment toward the middle or the end of the practice, when Anne was suggesting that someone lead and no one wanted to do it. And we were just awkwardly standing there. And she asked whether she should repeat what she wanted us to do. And you took the lead.

DF: Did I?

KdP: Yeah! I remember that moment, you were beside me. I could feel this sense of sound coming out of you. It felt to me that you had accepted the practice. You were creating more experimental sounds towards the end too, different pitches and harmonies, which was amazing to be a part of; it created raw material.

DF: We’re not used to that kind of practice. It’s like when you’re not an artist and someone gives you a pad of paper and says draw whatever comes to mind. Your mind immediately goes blank or you draw a flower or something really safe. But it’s really hard to get into the mindset of creating sound in this really particular way.

KdP: Well, I just realized that I don’t trust myself to make sound. I’m someone who doesn’t sing at all, terrified of being invited to a karaoke party. I don’t know what sounds are going to come out of my mouth, even when I intend to make an “ah” sound or whatever. Being in this situation of creating chants, or song-like tones, musical tones, I don’t know what’s going to come out. Which is, again, why when we started using words I was so much more comfortable.

DF: But I felt anxious about that part, too. We did an exercise where we went around the circle and every person said a word. I think it had to have an “A” vowel sound in it. I found myself self-conscious in this very kind of psychoanalytic way, that everyone was going to scrutinize this one word that I picked and be like, “What does that mean?” It added an extra layer of interpretative anxiety that I didn’t have with the sound.

KdP: It ended up being a lot of nature words. We all improvised towards a slow, collaborative poem, one word at a time, but still within a structure. I started playing. For example, Anne said we could use different languages, so someone else said “tree” and I said “boom” which is “tree” in Afrikaans, and then “tree” is spelled “tree” which is a stride when walking in Afrikaans. I started playing with the words in a way that I’m sure was totally unconscious to everybody else.

DF: It gives you more lateral moves when you’re working in language. When we were just matching tone for tone or sound to sound there is only so much variance there can be. My “ooh” to your “ahh.” My “oh” to your “ooh.”

KdP: How did you feel embodied in the rest of the day? Or did you?

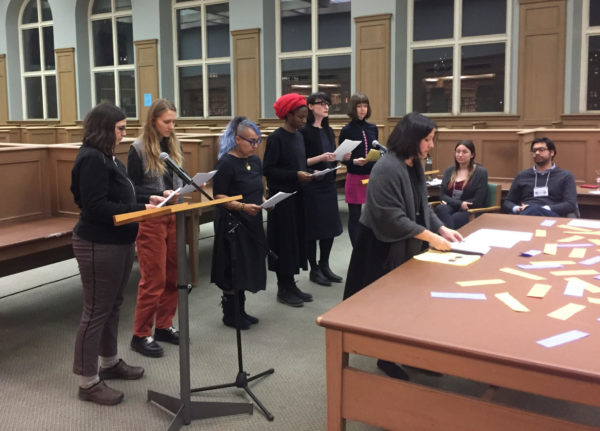

DF: I had a lot of really strong feelings because the focus on sound added an affective component to the work. I found Sachiko’s piece in the library, the collective voicing, incredibly moving.2 It’s a topic that’s close to me at this point. And I had been following on Facebook and there’s this big collective digital discussion that informs this piece too, which I’d been following and having a lot of intense feelings about too. But there’s something about the very powerful interplay between speaking and listening which made her and her chorus quite honestly move me to tears. I was trying to hold back because we had to perform afterwards and I didn’t know if I could get out of this headspace and back into this commanding role I thought I would have to portray for Margaret’s piece. So I was just very conscious of my body and having strong emotional reactions during the day.

Sachiko Murakami performs a collective voicing with a chorus of other writers. Photo by Deanna Fong.

KdP: There were some very tough topics during that final reading. Charlie Petch’s work was about trauma, and chronic pain, and death, and divorce. There was something about being in a library space and the gravitas of the institutional space and going back to the kind of traditional silence of that space which for me cradled some of the material that was being performed.

DF: But also trespassing that space and thinking about the difference between the expected silence of the library versus the very focused silence that Moez’s piece commanded. Which I think was intended to be—it wasn’t really about the exterior space, it created an interior space for reflection. And I think that’s how a lot of people received it, a lot of people closed their eyes. It wasn’t about connecting outwards, it was about connecting inwards.

KdP: It was definitely transgressive being in the library space. I mean we were eating in there and drinking and standing on the tables! Moving everything around.

The fact that the event was called Listen Deep, how did that affect your intention or form your experience?

DF: I’m a person who’s fairly conscious of the way I listen just in general. But it employed a lot of strategies that allowed me to listen differently. Not always deeply. I went through a spectrum of listening practices throughout the day, some of which were distracted, which were simultaneous, and some of which were very, very deep. For me it was more about multi-modal listening practice and pushing the different meanings that listening can have.

KdP: In contradiction to the kind of work that I do—I mean the fact that I’m part of SpokenWeb or the fact that I intend to focus my PhD dissertation at least partially through listening or the fact that I’ve been curating poetry events for years—despite all of those facts, I think I’m actually not a very good listener at all. I become very critical of myself when I’m in listening situations and find my mind wandering; sometimes attending a reading is less about the work being produced and more about just being present in the context of that production. I liked your word “multi-modal” listening practices because, for sure, there were fluctuations throughout, I mean there were 8 hours of listening! By the end of the day I was exhausted, but I do think that I listened with more intention, more attention, than I usually do. And I retained more. I was definitely primed to listen because of the initial meditative practice, but maybe it’s also got something to do with the level of activity required of the audience during most of the day. A number of the events required participation from the audience. For Moez’s, for example, the audience wasn’t only listening, we felt like we were part of an in-joke, and we could interject. Or there were a couple of interactive readings at the Library Plenary. There was the initial reading, choosing a book and just randomly reading passages from the book of your choice, listening to other people, but also being active, active in your listening, but also active in production of sound. A kind of listening practice that asks you to be involved. And that made it easier to retain information heard because it wasn’t as passive.

DF: I do want to bring up one of our interviewees who brought up an important counterpoint to this participatory listening, that participating in this way doesn’t necessarily foster all these exciting new encounters. People have very different comfort levels in participating. And certainly one of the people who we interviewed afterwards expressed that they definitely weren’t comfortable. This was at the library. Simply because they found the sound really overwhelming. So on the one hand, there is an expansive politics to it if you’re a person who’s really into participating, but one should also be careful of the ways that kind of participation also shuts people out who don’t want to participate in the ways expected.

KdP: I can understand that. But apart from the workshop which you had to sign up for, that you were consenting to be part of, apart from that, there was never a moment that you were forced to participate. I mean, not to discredit this person’s experience, but one could very easily not read out loud.

DF: But also, the withdrawal of participation while listening becomes overwhelming. It’s just a question. We approach this kind of work from a utopian perspective that it’s doing something that’s broadening the way we normally receive literature. But I think this is a valid question: is it always that? Or is there a point at which it becomes merely spectacle?3

KdP: I think this series of events was a very self-conscious attempt at broadening the format of the poetry reading and putting it in conversation with performance art, site-specific work, performance just straight up, performance poetry.

DF: I think you and I both experienced this as a real broadening of the genre of poetry and what a poetry reading can do, but maybe the question is to what end? I mean this in terms of when we consider a certain social impetus behind the poetry reading. What do we think a poetry reading is in the first place? How do participatory modes broaden what a poetry reading does? Is this broadening merely aesthetic, or is it social—political even?

KdP: I’ve definitely read some articles about the “traditional” poetry reading as a form, and people who are like, “Why are we doing this? This is such an uninteresting format.” And then we all continue doing it. We put people on stage who don’t necessarily perform, who are extremely introverted, who don’t have any background in performance, and put them on stage being like, “Hey, you’re a spectacle now.” So I think there is some interest, especially now, to broaden the poetry reading’s minimalism or to think about it more intentionally. I’m wondering whether, to a degree, some art forms have developed or devolved to become more minimalist. This is a broad statement to make, but take, for example, theatre which can be extremely ornate, large scale, with five acts, and a large cast of actors. These days, this maximalist approach then becomes increasingly pared down to maybe a one person intervention in a gallery space. And that’s almost adjacent to a poetry reading again. Different art forms are rubbing up against one another to the point that the poetry reading starts embodying other forms or comes into conversation with other art forms. And that initiates a curiosity to see what will happen if we push it and expand it.

Notes

1 Julia Polyck-O’Neill: I have heard the opposite from others who have spent time there, so I find this interesting! I only attended and participated in the evening reading, and remember feeling uneasy about entering the highly institutional space when I knew the readings would be dealing with personal topics. But the act of inhabiting the space for the duration of the event felt like a kind of reclamation of the institutional architecture. Like our bodies and voices were subverting the norms of the space.

2 Julia Polyck-O’Neill: I was part of Sachi’s chorus and I was also very moved by the piece. We were given our scripts ahead of time and so the language of the piece wasn’t a surprise, but the effect of the experience of reading the work as a group (noting that many of us hadn’t met before the event) combined with the heart-wrenching theme of the work made for an incredibly affective and embodied moment.

3 Julia Polyck-O’Neill: I have to admit, I often wonder this when witnessing performances that demand more active forms of participation. Does the format seem necessary to the work/performance, or is it a kind of accessory (or impediment) to the act of (actively) listening? As an audience member and sometimes-organizer, I have been called on to “participate” in readings in ways that have made me physically and aesthetically uncomfortable (meaning that I felt that the act of receiving and interpreting the work was actually being interrupted or disrupted by the need to participate). But, I didn’t feel this way at Listen Deep. It gave me a lot to think about.