Clip 01 – 19:30-20:00 (OBJ-287_SideB)

LAYTON: “I rather envy Dorothy, her warmth and her concern, and above all her confidence. I lost that. I don’t believe in any political solution. And I feel that things have not changed as far as the literary scene is concerned. I began by attacking the academicism, the remoteness from reality and the gentility. And if I had to write things today, I think I would attack the same things.”

Clip 02 – 18:38-19:11 (OBJ-287_SideA)

MARRIOTT: “Listening to Dorothy makes me feel as if I had done nothing in the 30s and knew absolutely nothing about what was going on in the Canadian literary scene… and I guess that that was really quite true. As Sandra has said I grew up in Victoria— – I went to a girl’s private school where the main purpose of our education seemed to be to turn us into nice polite English ladies and maybe to play grass hockey well, which is something I never succeeded in doing[.]”

How might a public dialogue between three modernist poets in 1978—about poetry written in the 1930s and 1940s—remain relevant to thinking about the conditions of Canadian literature today? Dorothy Livesay, Anne Marriott, and Irving Layton, as we have explored in Take 1 and Take 2, examine the shifting relationships between politics, nation, and poetry that are foundational to understandings of what constitutes ‘modernism’ in Canada during these periods. In particular, in these two clips Marriott and Layton articulate their positions concerning ‘political’ poetry, and separate themselves from Livesay’s activism and political idealism. Given that the panel discussion takes place alongside the 1977 publication of Livesay’s book Right Hand Left Hand: A True Life of the Thirties, Livesay’s comments about poetry’s role in the 1930s often reflect the renewed academic interest in the 1970s in documenting “the poverty of the new immigrants, the low wages and long hours, the return of veterans expecting to be heroes, but finding only unemployment” (SFU recording). For her, 1930s political literature’s cultural importance is documentary, residing in its ability to function partially as a mode of recording the material social struggles of the past, and therefore should be recuperated for present and future generations in service of building a more equitable society. Livesay also passionately recalls the importance of the growing network of little magazines in the 1930s and 1940s, such as Masses (1932–34), New Frontier (1936–37), and Contemporary Verse, (1941–52) which helped facilitate Canadian modernist poets to share their work amongst themselves and to potential new audiences. Importantly, these venues served as alternative literary spaces that could function—if only briefly—outside the narrow purview of the university and other dominant cultural and literary institutions.

As Livesay recounts this literary and social history to the panel’s audience in 1978, she takes on the role of social documentarian, as she advocates for the importance of political engagement through literary activity. In contrast, Marriott often speaks frankly from a more personal position, as she admits to how her relative privilege may have led to the opportunities she was afforded as a poet during this period. As she recounts her childhood at an all-girl private school, she also addresses how her comfortable upbringing in the “green cocoon” of Victoria, British Columbia had mostly sheltered her from the effects of the Great Depression experienced by other Canadians (SFU recording). It wasn’t until 1937, when Marriott took a trip to stay with relatives at their prairie farm in Saskatchewan, that she recalls becoming more aware of the Depression’s widespread impact across the country, a shift that directly impacted the kinds of topics she chose to write about in “The Wind, Our Enemy.” Meanwhile, Layton stands by his earlier position in the 1940s, continuing to rail against what he views to be the “gentility and academicism” of Canadian literary culture. As the second take of this series explained, Layton’s desire for new forms of literary rebellion took shape through his involvement with the little magazine First Statement. While both the First Statement and Preview group of editors defined themselves as anti-fascist in the wake of the Spanish Civil War and impending second World War, First Statement was formed in opposition to a literary culture premised on the values of civility, traditionalism, and maintaining class hierarchies, which the magazine’s editors felt was unable to properly confront the disorderliness, discomfort, or eroticism inherent to the vast psychological complexity of lived experience.

Recalling the clip from ‘Take 2’, in which Marriott expresses her enthusiasm for little magazines and the increased publishing opportunities for emerging poets in the 1970s, Livesay’s interjection—her question of whether this broader access is necessarily a “good thing”—suggests a skeptical position. What follows these comments is an exchange between Marriott and Livesay about whether or not there is, in Livesay’s words, any “real political poetry” being written in the 1970s. While Livesay is certain that the moment for political writing is over, Marriott is optimistic as she considers whether or not the 1970s is grappling with “those same political things to fight about” (SFU recording). For Layton, Canadian poetry in 1978, as he states earlier on in the recording, is “as gutless, as bloodless as [he] found it in 1942,” and laments its lack of attention to the “great psychological and moral issues of our time” which are not located in politics, but in “the heart and soul of man” (SFU recording). Despite their differing positions, Livesay and Layton both express a certain degree of discontent with the state of contemporary poetry according to their own particular values as 1930s and 1940s modernists.

To what extent does Livesay, Layton, and Marriott’s framework for literary value in 1978 fail to recognize other innovative work being written at the time of their discussion? At different points in the recording, both Livesay and Layton make certain assumptions about print being a marker of literary value and cultural legitimacy, a view that Livesay echoes when speaking of poetry readings as an extension of print, allowing poems to finally be experienced “in the air” as opposed to “on the page” (SFU recording). Recalling Canadian dub poet Lillian Allen’s admonition, “remember, always a poem, once a book,” however, highlights the way this perspective runs the risk of obscuring other histories of oral practice within literary culture, such as the legacies of Indigenous and dub poetics (Gingell 223). For the history of dub poetry, a performance-based poetry that evolved out of dub music in Kingston, Jamaica, 1978 was an important year for the later development of dub poetry in Canada. Inspired by Oku Nagba Ozala Onuor’s—also known as the “father” of dub poetry—performance at the World Festival of Youth and Students in Cuba, Allen began to dedicate herself to the practice of dub poetics in her community of Toronto, Ontario, revealing that key historical moments for poetic innovation in Canada have not only taken place through the pages of poetry periodicals, but through other mediums and spaces such as live venues and musical performances (Sullivan 193).

During the Q&A, Livesay also expresses concern that the increasingly “naval-gazing” poets of the 1970s have reverted back to “writing to each other,” rather than to wider audiences (SFU recording). While Livesay may be wary of repeating the coterie model of previous literary movements, this criticism might also parallel a tendency among Anglo-European literary editors, as Cree-Swedish poet Neal McLeod writes, to “sometimes miss the point of Indigenous poetry—for example, its rhythms and movement through our respective languages, the meaning and significance of Indigenous words, our poetic humour, and the societal context from which our words are derived” (Mcleod 4). In contrast to Livesay’s fear of self-referentiality being incompatible with her view of what makes poetry ‘political,’ Indigenous poetics, as McLeod states, “is inherently political because it is the attempt to hold on to an alternative centre of consciousness, holding its own position, despite the crushing weight of English and French” (12).

Therefore, to reconsider either Livesay’s or Layton’s perception that 1978 is a year during which “no real political poetry” is being written can serve as a starting place for broadening our understanding of the literary activity of the time, as well as to better grapple with how literary value is defined through the medium of a literary event. From our vantage point in the 2020s, the oral nature of the recording thus draws more attention to the contextual frame surrounding each of the three poets’ historical reflections on the relationships between print, poetry readings, reading audiences, and themselves as canonized Canadian modernist poets. In these ways, the SFU panel discussion is not only a document of oral history, providing us listeners new insight into a lesser-known period of literary history. Upon closer listening, it also demonstrates how socially-engaged poets such as Livesay, Marriott, and Layton create literary history anew in the present—as they reflexively construct and deconstruct, as well as mythologize and document, a Canadian modernist literary history that still has the power speak out against its own nationalistic tendencies in support of a more inclusive future.

Works Cited

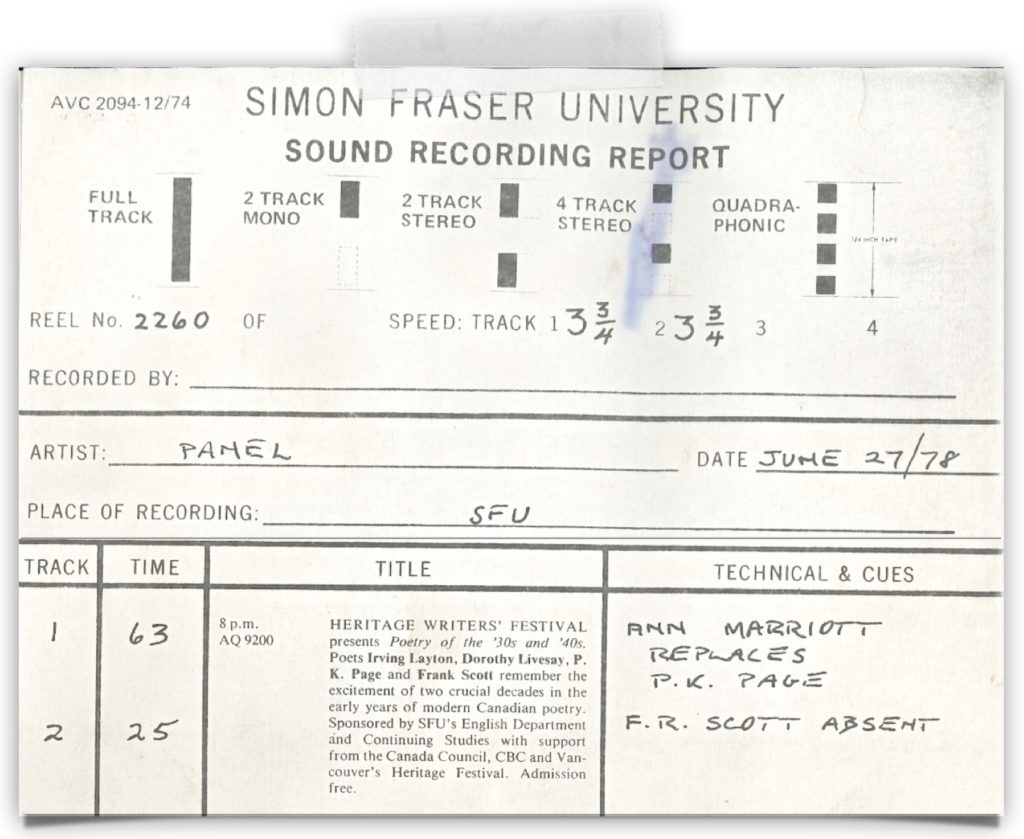

“Dorothy Livesay, P.K. Page and Ann Marriott: Poetry of the 30s and 40s.” 27 June 1978. Sound recording. F231-1-2-0-0-26, Simon Fraser University Sound Recordings Collection. Simon Fraser University Archives, Burnaby B.C. April 5 2021

Gingell, Susan. “Always a Poem, Once a Book”: Motivations and Strategies for Print Textualizing of Caribbean-Canadian Dub and Performance Poetry.” Journal of West Indian Literature 14.1, 2005, pp. 220–59.

McLeod, Neal. Indigenous Poetics in Canada. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2014.

Sullivan, Paul. “Canada’s Poetry and Dancehall.”Remixology: Tracing the Dub Diaspora. Reaktion Books, 2014, pp. 188–208.