LIVESAY: “But in the 30s there were absolutely no readings… I—we were much too embarrassed or shy even to read to each other. Everything was the printed word. And that is why the magazine was such an important thing… Poets were working together to produce a magazine, and to try and get an audience for it[.]”

In their public discussion at Simon Fraser University in 1978, the three poets Dorothy Livesay, Anne Marriott, and Irving Layton each emphasize the significance of print to the trajectory of modernist poetry written in the 1930s and 1940s. In this particular clip, Dorothy Livesay’s statement, that in the 1930s “Everything was the printed word,” is in response to a question posed by an audience member about the prevalence of public readings during this period. Given that the object of this blog series is an audio recording of a public event—specifically one that documents an oral history of the poets’ personal encounters and involvement with print—the audience member’s question draws attention to the shifting relationships between writers and readers (or listeners), and the different contexts for cultural transmission that have constituted Canadian literary culture more broadly between the 1930s and 1970s.

As Livesay’s statements in the clip introducing this blog series highlights, the dominant role of print during the 1930s arises in the context of a literary culture marked by a growing concern for the myriad social issues impacting the lives of Canadians in the wake of the Great Depression of 1929, which lasted until Canada declared war on Germany on September 10th, 1939 (Rifkind 5). Livesay also suggests in her introductory comments that many of the writings produced during the period have been overlooked by historians and critics. In an analysis of women writers who formed the Canadian “literary left” in the 1930s, Candida Rifkind writes about a tendency in the history of English-Canadian literary criticism, in which the Depression has often been characterized as a period of cultural drought, caught between the flurry of literary nationalism in the 1920s and the post-war modernism of the 1940s (6). In fact, it was in light of the period’s immense economic hardship and political unrest that literary forms coalesced with the aim of both documenting and transforming social injustices (5). The widespread economic impacts across the country had the unexpected effect of bringing together many professional ‘white collar’ writers and part-time working-class poets in new ways, as they often published alongside each other in the same venues seeking to amplify diverse perspectives. These writers also frequently shared collective ideals to address social issues and imagine new paths towards a more equitable world. While leftist presses, periodicals, and newspapers flourished in place of those arts and publishing venues that had not survived during the Depression, the newspapers, magazines, radio, and theatres that continued to proliferate as avenues for cultural consumption sought to connect with a growing audience for not only poetry, but also plays and short fiction. New media possibilities for mass readership in both Canada and the United States therefore instilled a shift in emphasis from the authors’ literary production to the consumption of poems by potential readers.

Livesay’s own poetry also reflected a shift towards social concerns in the 1930s. While her first two collections, Green Pitcher (1928) and Signpost (1932) had been influenced by the aesthetic modernism of other Canadian poets such as Raymond Knister and W. W. E. Ross, in particular their experiments with imagism, Livesay aimed to connect her poetic practice with her growing involvement in social activism and Marxism. In a 1936 radio talk titled “Decadence in Modern Bourgeois Poetry,” Livesay critiques the “lack of socially valuable meaning” put forward in high modernist poetry, including poets such as T. S. Eliot, and instead advocates for a socially engaged poetics that extends beyond the textually confined poem in its “appeal to a very small group of people who happen to have had the same prolonged education and the same refinement of the senses” (Livesay 64). In this way, Livesay’s desire for a poetry that reflects and seeks to ultimately transform the material struggles of the times simultaneously confronts the question of audience in light of the emergent media landscape and discourses concerning the revolutionary potential of mass readership.

Along with this redirection toward social subject matter, Canadian socialist-modernist poets such as Livesay focused their energies—to varying effect—on the growing influx of “little magazines,” defined as a type of non-commercial literary, arts, or cultural periodical that emerged alongside the rise of literary modernism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Irvine 4). Rather than reinforce the elitist coterie culture that had already been prevalent within avant-garde modernist circles in North America and Europe, this group worked to establish new avenues of solidarity between middle-class and working-class writers and readers through the techniques of mass marketing, advertising, and self-promotion. The publications, however, were often short-lived due to the lack of national arts funding opportunities. For many modernist and leftists who were, according to Livesay, trying “to get an audience,” there was also frequently a disconnect between an idealized readership, often imagined in terms of ‘the masses,’ ‘the public,’ or ‘the people,’ and the reality of the literary culture’s pre-given audience made up of ‘self-initiated’ members (Irvine 17-18).

Listening to Livesay’s comments in 1978 in front of a live audience therefore highlights the difference between the image of poets who were “too shy” to read “even to each other” in the 1930s and the new literary conditions that facilitated the existence of this particular event at Simon Fraser University. Following the introduction of the Massey Commission in 1949, an initiative to investigate the state of arts and culture in Canada, the Canada Council of the Arts was created in 1957 to fund the production, study, and enjoyment of artistic works on a national scale. In this context, Livesay’s following statement, that readings emerged later as a national phenomenon in the 1960s and 1970s, is correct. Orality and sound, however, nevertheless played a role in the dissemination of modernist poetry in the decades prior. Livesay explains that in the wake of the launch of the Vancouver-based little magazine Contemporary Verse in 1941, her friend and literary editor Alan Crawley and the poet Earle Birney had organized their own poetry readings and talks. Crawley and Birney, who sometimes made appearances on the CBC, also hosted readings in highschools throughout Vancouver. Sound was also a crucial poetic modality for Crawley, who was blind, and known for his practice of memorizing and reciting poems aloud at public gatherings. At Crawley’s suggestion, Livesay also started adapting poems for a radio audience, and by the late 1930s had joined Crawley in presenting public readings on the CBC (Aguila-Way 40). Therefore, despite Livesay’s initial claim that “there were absolutely no readings” in the 1930s, the oral-based nature of the SFU event draws parallels to other moments in this literary history in which poets such as Livesay were interested in exploring the possibilities of sound and speech for connecting to new readers in times of crisis and social change.

Works Cited

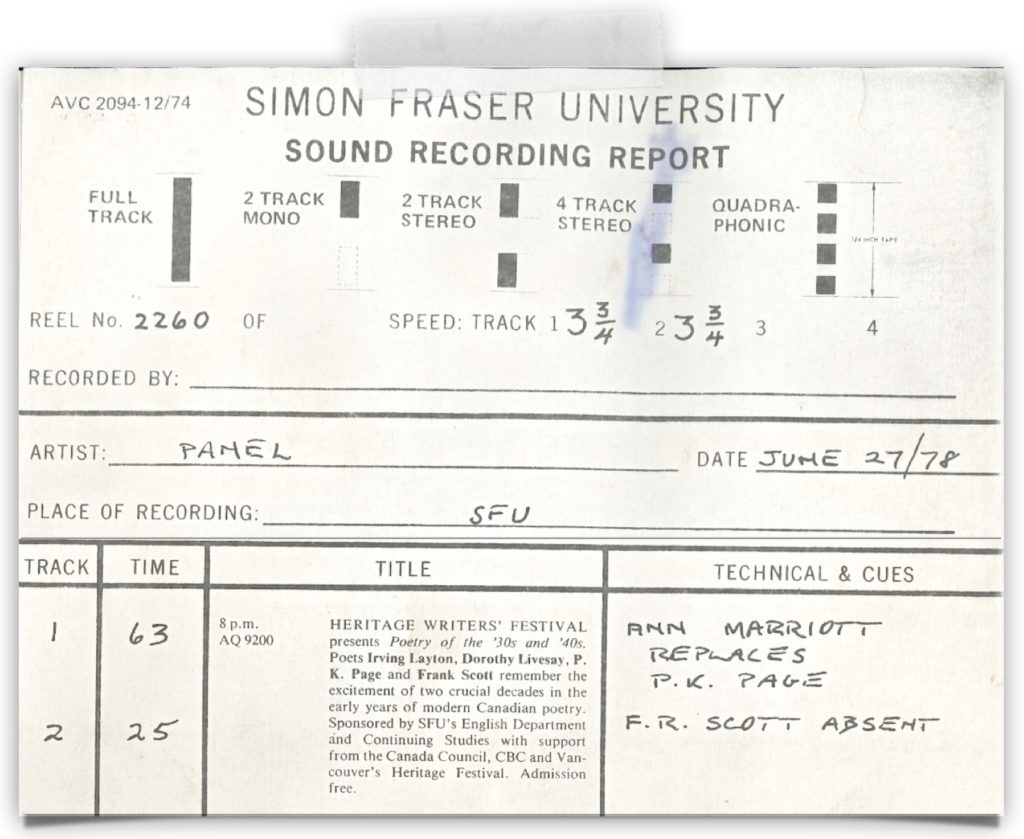

“Dorothy Livesay, P.K. Page and Ann Marriott: Poetry of the 30s and 40s.” 27 June 1978. Sound recording. F231-1-2-0-0-26, Simon Fraser University Sound Recordings Collection. Simon Fraser University Archives, Burnaby B.C. April 5 2021

Aguila-Way, Tania. “Griersonian ‘Actuality’ and Social Protest in Dorothy Livesay’s Documentary Poems.” Double-Takes., University of Ottawa Press, 2013, p. 39.

Irvine, Dean. Editing Modernity: Women and Little-Magazine Cultures in Canada, 1916–1956. U of Toronto P, 2008.

Livesay, Dorothy. Right Hand, Left Hand. Press Porcepic, 1977.

Rifkind, Candida. Comrades and Critics : Women, Literature and the Left in 1930s Canada. University of Toronto Press, 2009.