ShortCuts Introduction: Canadian Poetry of the 1930s and 1940s—Listening to Literary History

May 19, 2023

Teddie Brock

ShortCuts on SPOKENWEBLOG is a series of critical commentaries about short clips selected from audio collections across the SpokenWeb network. This post introduces a three-part series by Teddie Brock, all based on a 1978 panel discussion with Dorothy Livesay, Anne Marriott, and Irving Layton, as recorded on audio preserved at the Simon Fraser University Archives. Check back on SPOKENWEBLOG for the next installment of this close listening to the archives as they roll out over the coming weeks.

LIVESAY: “It is only in our time that the historians have documented the poverty of the new immigrants, the low wages and long hours, the return of veterans expecting to be heroes but finding only unemployment, the ruthlessness of the state in bringing in the police against peaceful demonstrators. Yet all the time there were documents to be had and found—for the writers were writing. Their books were being published all through the ‘20s[.]”

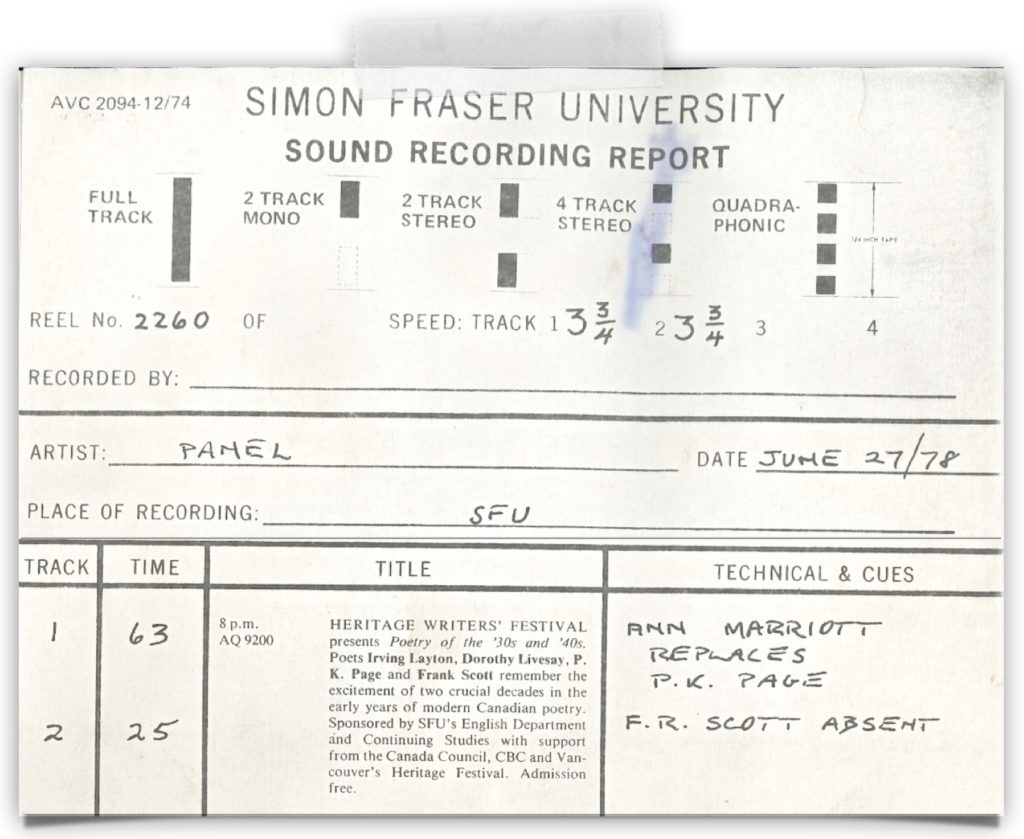

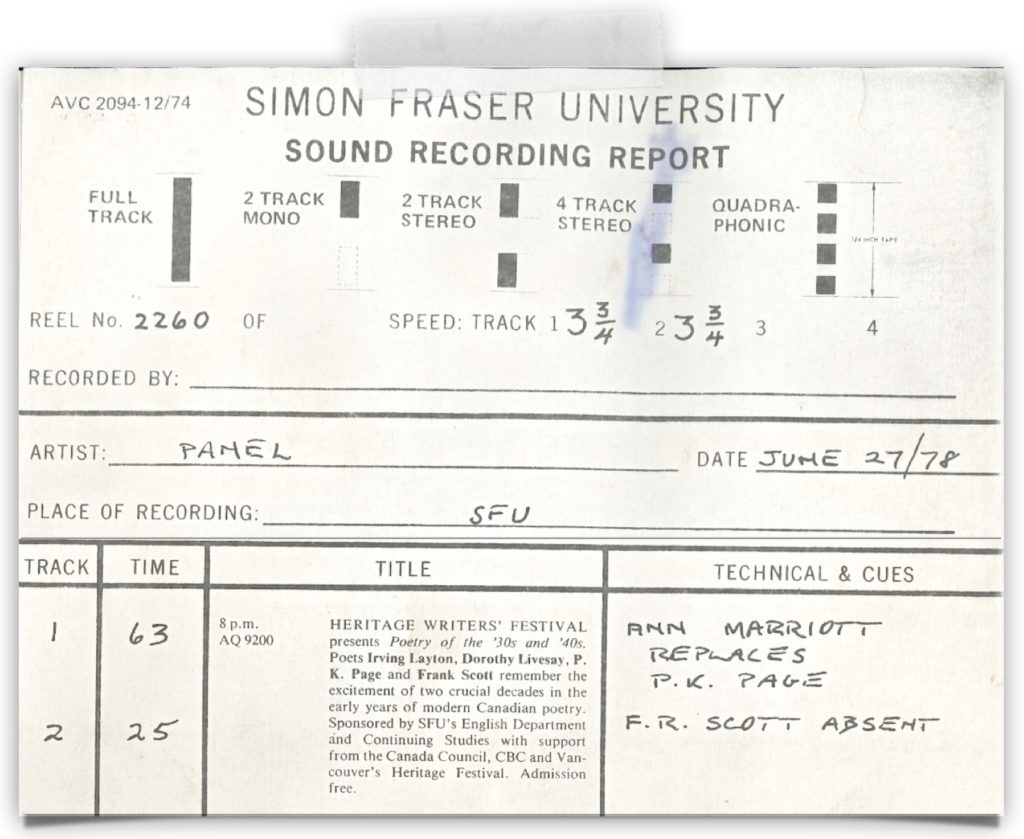

On June 27, 1978, poets Dorothy Livesay, Anne Marriott, and Irving Layton were invited to speak at a panel discussion sponsored and hosted by the departments of English and Continuing Studies at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, British Columbia. As part of the Vancouver Heritage Writers’ Festival, a public literary series at the time, their conversation centered on Canadian literary culture and modernist poetry during the 1930s and 1940s. Two other distinguished poets, P. K. Page and F. R. Scott, had originally been invited to participate but were ultimately unable to attend the panel. Marriott and Layton were invited to speak in their stead.

In this audio clip, Livesay addresses what she claims to be the unique conditions of “our time”—specifically, the late 1970s when the event was recorded. As she insists, it is “only” in the time of recording, in 1978, that the defining social struggles of the 1920s and 1930s were being given appropriate historical attention. The event, titled “Poetry of the 1930s and 1940s,” also took place within the year following Livesay’s publication of Right Hand, Left Hand: A True Life of the Thirties. Assembled by Livesay, this book is a compilation of various essays, letters, and clippings illustrating the cultural and political significance of the period as well as Livesay’s engagements as both a poet and leftist activist. By turning to the writers who pressed on to document the experiences of their times, her comments emphasize the idea that various cultural and political conditions are always at work in shaping our understandings of both the present of “our time” and the historical past—a past that is never readily accessible by default, but is actively revitalized through the work of archiving, curation, and communal sharing to ensure its preservation and relevance into the future. In the context of this particular discussion, such documents “to be had and found” are thus given renewed attention, finding a momentary home through the oral exchange between the three poets and their listening audience at Simon Fraser University in 1978.

Given the retrospective nature of the panel topic, each poet is asked by the event’s facilitator, Sandra Djwa, a professor of English at Simon Fraser University at the time of the recording, to provide a personal introduction followed by a historical overview of a particular period. The three poets then engage in an open discussion, which leads to a question-and-answer period with a live listening audience. Following Djwa’s opening comments, the first poet to speak is Livesay, who recounts how she began writing in Ontario in the late 1920s and continued throughout the 1930s while remaining strongly committed to socialist activism. Marriott elaborates on her experiences growing up on Vancouver Island and her later trip to a farming community in Saskatchewan to stay with relatives, which inspired her to write the celebrated poem, “The Wind Our Enemy.” The poem was first published by Ryerson Press with the support of Dorothy Livesay’s father, J. F. B. Livesay, in 1939. As one of the most anthologized documentary long poems of the 1930s, “The Wind, Our Enemy” blends aspects of imagism and realism to portray the environmental and social hardships of the prairie region during the Great Depression. Finally, Layton concludes with comments about his involvement with First Statement, a Canadian little magazine of modernist poetry, and the shifting literary scene in the early 1940s in Montreal. As each poet recounts their memories and sentiments about Canadian literary culture, it is clear that their perspectives are distinct from and at times contradictory to one another. In listening to the unique qualities of each poet’s voice and rhetorical style in the context of a shared dialogue, such differences are experienced most viscerally.

In their representative positions as modernist Canadian poets, the event also serves as an occasion to draw strong parallels between them—specifically in terms of their shared contributions to the development of an alternative national literature. To frame the event’s literary concerns from a national perspective, Djwa recites the satirical poem titled “The Canadian Authors Meet” by the social democrat and modernist poet F. R. Scott. Written in 1927, the poem’s gendered, classed, and generational expression of literary politics has been invoked frequently by critics and poets alike to analyze the cultural divergence between the traditionalists—also known as the Victorian or “Maple Leaf School”— and the emergent modernists in Canada during the 1920s (Kelly 54).

The Canadian Authors Meet

F.R. Scott

Expansive puppets percolate self-unction

Beneath a portrait of the Prince of Wales.

Miss Crotchet’s muse has somehow failed to function,

Yet she’s a poetess. Beaming, she sails …

[Click here to read the full poem.]

Although Scott had been aware of women poets such as Dorothy Livesay, who had been experimenting with modernist forms throughout the 1920s, the poem’s feminized figure of “Miss Crotchet” serves as a gendered representation of the anti-modernist literati’s aesthetic and political tendencies that Scott associates with the Canadian Authors Association (CAA), a literary group composed predominately of middle-class women in the 1920s and 1930s. As Candida Rifkind illustrates, however, the poetic preferences of the CAA membership ranged from lamenting the loss of authenticity brought on by the advent of new technologies, and formally conventional works about “home, hearth, and Empire”—such as those written by one of the group’s most popular poets, Edna Jacques—to the aesthetic modernist experimentation of poets such as Livesay and Marriott (8). The poem’s gendered critique of aging bourgeois femininity also represents the “broader masculinist rhetoric” that was characteristic of Canadian socialism during the Depression (Rifkind 11).

While Scott’s poem not only critiques the traditionalists’ preference for rhyme, metrical forms, and archaic diction by incorporating these elements, it also draws attention to the cultural values and practices fostered by groups such as the CAA that functioned to overshadow the innovative poetics of some of its members, instead elevating subject matter that adhered to a politically conservative image of Canadian nationalism and folk authenticity. In other words, rather than focus its critique on individual poets labouring to replicate traditional forms in isolation, Scott’s satire of traditional poetry emphasizes the relationship between the elitist social practices of literary communities in Canada and the conservative aesthetics derided by literary modernists who sought alternative ways to engage poetically with the question of place and nationality. The figure of “Miss Crotchet,” who boosts and entertains her fellow poets— “the literati”—with a “dear Victorian saintliness, as is her fashion” could be understood to parallel Scott’s position as he gestures toward his own audience of anti-traditionalist poets in order to define and advocate for a distinct literary modernist poetics and culture in resistance to the genteel poetry that preceded it (Scott, lines 3–12). For the early modernists concerned with forging alternative paths toward a “new” Canadian literature, poems are thus understood as always entangled with social relations and the cultural contexts in which they are produced, published, and distributed. Along similar lines, Livesay, Marriott, and Layton’s discussion also highlights the extent to which the various forces of community relationships, cultural institutions, and regional politics are inseparable from understanding their own personal trajectories as poets.

Therefore, what might be most valuable about the discussion (specifically, our archived recording of it) is not to approach it as simply a vehicle of fact—a document of what happened in the past— but as an opportunity to hear how narratives surrounding modernist and contemporary literature are actively constructed (or contested) as distinctly “Canadian” through the context of an institutional public dialogue. Further, given the three poets’ emphasis on print’s significance during a time in which “everything was the printed word,” as Livesay claims later in the recording, the act of listening prompts us to ask: what does it mean to think through the history of print publication through sound and voice? What are the narrative or political implications of the presence (or absence) of certain voices throughout this discussion? And how might these poets’ perspectives resonate differently for listeners in 1978 compared to today? In future posts, these questions will be considered through a closer listening of short excerpts taken from the 1978 recording, alongside brief reflections on the multi-layered processes of listening and writing about archival audio and literary history.

Works Cited

“Dorothy Livesay, P.K. Page and Ann Marriott: Poetry of the 30s and 40s.” 27 June 1978. Sound recording. F231-1-2-0-0-26, Simon Fraser University Sound Recordings Collection. Simon Fraser University Archives, Burnaby B.C. April 5 2021.

Kelly, Peggy. “Politics, Gender, and New Provinces: Dorothy Livesay and F.R. Scott.” Canadian Poetry, vol. 53, 2003, pp. 54–65.

Rifkind, Candida. Comrades and Critics : Women, Literature and the Left in 1930s Canada. University of Toronto Press, 2009.

Scott, F.R. “The Canadian Authors Meet.” Canadian Poetry Online: University of Toronto Libraries, 2000, https://canpoetry.library.utoronto.ca/scott_fr/poem3.htm. Accessed 21 July 2022.