On Literary Machine Listening and Pedagogy: The Praxis Studio with Julie Funk, Faith Ryan, and Jentery Sayers

February 26, 2021

Emma Telaro

This summer, I reached out to Jentery Sayers with some questions about his research on voice user interfaces. He told me his research had veered in new directions and proposed that we discuss other related projects happening at the University of Victoria, where he teaches, and runs the Praxis Studio for Comparative Media Studies. He suggested I get in touch with Julie Funk and Faith Ryan to learn more about what’s happening at the lab. Here’s a peek into their innovative work: ‘literary machine listening’ and teaching audio in fiction in the classroom.

Emma: Hi Julie, Faith, and Jentery! Thanks for agreeing to participate in our Symposium interview series, and for offering to guide us through the exciting SpokenWeb research happening at UVic. Can you tell us about the activities and research going on at UVic’s Praxis Studio for Comparative Media Studies?

Jentery: Thanks for taking the time to chat with us, Emma. We really appreciate it. The Praxis Studio is a group of researchers who study the aesthetics and politics of media by blending theory and history with storytelling and prototyping. We’re curious about experimental methods for research related to media and fiction, and most of us are in English and Cultural, Social, and Political Thought at UVic. I direct the Studio, but the projects are student-led. Right now, we’re focusing on games, science fiction, and fantasy alongside our work with SpokenWeb on literary audio, where Julie’s leading the way. The Studio is a member of SpokenWeb’s pedagogy task force, and we’re invested in how experimental methods unfold in the classroom: how, for example, students might treat audio as a form of inquiry while learning about media and fiction.

Emma: That all sounds really cool. I know that Julie is leading a project on literary machine listening. So, Julie, what is that—literary machine listening?

Julie: Great question – I’m not entirely sure yet! I think, in broad strokes, literary machine listening is an attempt to bridge the gap between the abyss of consumer understandings of machine learning and listening technologies (computational audition), where processes and logics are typically obscured by interfaces, and “inputs” are sensory information rather than data. I’m building on listening practices like Michel Chion’s Three Listening Modes and Tanya Clement’s Deep. Listening and putting them together in a sort of choose-your-own-adventure technique. At this stage, I think of literary machine listening as a “low-tech” pedagogical tool for teaching and practicing critical analysis of “literary audio”—a concept that probably needs unpacking, but that’s another project in its own right.

As a pedagogical approach, literary machine learning is organized through a generalized version of the logical processes you might find in computational audition. Listeners are asked to partake in these processes as they listen to literary audio. But, instead of identifying and organizing sounds like an audio classifier would do, they apply machine logic to reach critical and meta-critical claims about the literary audio in question. This process is guided by a library of prompts that I aim to grow as the project continues. I am running a few workshops, such as the Listening Practice for SpokenWeb I guided on February 24th, and participants’ responses thus far have been really generative. They are pointing me to new ways to navigate the critical analysis of sound through the procedure of literary machine listening.

You might say that, in practice, literary machine listening is a series of “reflexive runs” through machine logic. My goal is to ask listeners to attune to a procedure of listening that can be shared by people and computers, including content that might otherwise be considered “garbage” and might be scrubbed by a particularly sharp audio classifier or a scholar trained in a particular habit of listening. While semantic listening, or listening for messages, is certainly one way to get at literary machine listening, I’m also interested in how we might use it to create non-semantic, descriptive sound “profiles” of literary works: how a narrator’s sticky, wet mouth sounds when recording an audiobook, as one particularly visceral example. Framing listening to literary audio in this way is not only a technique suitable for audio artefacts in a world of digital recordings and artificially produced sounds (some of which are becoming increasingly literary), but also, and perhaps more importantly, an approach that asks listeners to be intellectually present and attentive to each critical step, including the taken-for-granted recognition and immediate dismissal of garbage sounds, as well as the meta-criticisms of audio: the subsonic and supersonic ends of criticism, if you will.

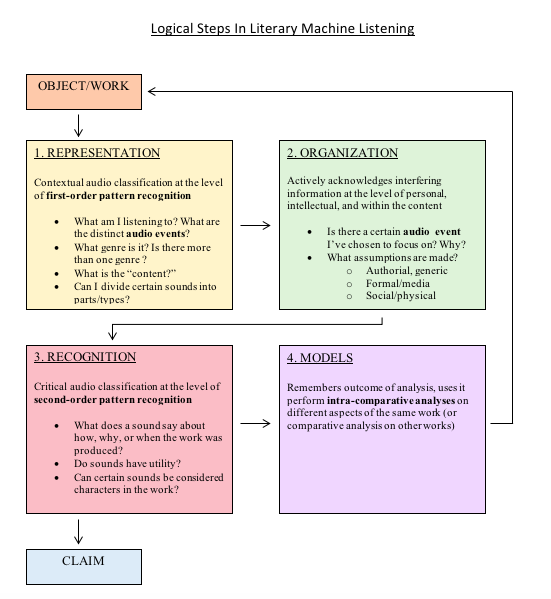

My approach moves through four steps: representation, organization, recognition, and finally modelling. I’ve included a figure (fig. 1) that outlines them. Notably, the approach is a positive feedback loop with the end of a model being able to point back to the object, allowing for intra-comparative analysis or meta-analysis until the listener articulates an argument about what they’re hearing. During the SpokenWeb listening practice on February 24th, we experimented with these steps while listening to a clip of Samuel Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape (a 1960 performance directed by Alan Schneider at the Provincetown Playhouse).

fig. 1. Julie Funk, outline for Literary Machine Listening

fig. 1. Julie Funk, outline for Literary Machine Listening

Emma: That’s a helpful synthesis. I wonder, what sorts of political and ethical concerns is literary machine listening engaging with?

Julie: I think the main concerns that literary machine listening engages are accessibility and, specifically, accessible digital literacy. Even though it’s based on the logic of computational audition, literary machine listening has no digital or otherwise computational interface; it can be modelled with just a pen and some paper, maybe a digital audio file and player, but even those aren’t necessary. So, it becomes a pedagogical approach that demonstrates steps in the machine logic of audio classifiers without demanding any advanced knowledge of machine learning systems or specialized software.

Because literary machine listening requires listeners to attune to how audio is presented and distributed, along with what the literary contents of that audio may be, it also presses listeners to think about bias in design, particularly bias in algorithmic design. If you perform some of the steps, you can begin to see where sample biases, preconceived notions, and deterministic design come into play in your own listening practices. A sort of bias-check is included in the “organization” step of my approach, not to force listeners to reject their perspectives, but to prompt them to acknowledge the presence of those perspectives and their influence on critique.

Emma: How has the conversation on literary machine listening evolved since its beginnings? How was it sparked in the first place?

Julie: This project came out of conversations with the SpokenWeb pedagogy team at UVic and a graduate seminar on “Media Aesthetics” that Jentery taught during the spring of 2020. I’m grateful to everyone in those communities, as well as SpokenWeb collaborator, Brian McFee, who gave me great guidance and feedback at different moments in this project.

Originally, I wanted to create a small Python-based audio classifier to do the first step (representation) for the listener. That way, the analytical steps would be a responsive and more dialogic engagement between machine listener and human listener, with a person being responsible for the final literary critique or claim. The idea of growing a critique out of a dialogue with a machine learning system was a really intriguing experiment to me because I wanted to know if the classifier would, or could, “set the tone” for the rest of the analysis. It was ultimately a question of co-production between all the actors involved. What would happen if the classifier’s interpretation sounded “wrong” to human ears: the classifier labels the audio “bird song,” for instance, but someone is certain they hear a “whistle.” How do you negotiate the rest of the analysis from an initial point of conflict in classification? What would happen if you humoured the classifier and interpreted whistle sounds as bird song? How would it change the meaning of the audio and its narrative? I imagined an initial iteration of this project working best in recordings of literature like stage plays that are rife with sound effects.

I’m still interested in those questions and may continue to pursue them, but I was guilty of putting the cart before the horse with my original vision. What I’m now calling literary machine listening is, I think, the necessary first step: to map out what computational audition is and does, and how that process translates into a reflexive and conscious procedure for human listening. The benefit of moving the goalposts was that I now have a low-tech approach that can not only be applied to a richer array of literary audio but also helps listeners to perform the “listening logic” of computational audition before adding a technology as an interlocutor into the mix. My current draft of the research is heavily inspired by how Mimi Onuoha and Mother Cyborg wrote A People’s Guide to AI. It opens discussion at the very beginning of the process, without making assumptions of skill or background in reading, listening, or programming.

Emma: Have you or Jentery brought literary machine listening into the classroom?

Julie: I offered a workshop in Jentery’s “Readers Are Listening” graduate seminar in the fall. It was an opportunity for me to see if the technique would be valuable to others. I was surprised by the engagement with the workshop. We listened to samples of Toni Morrison’s audiobook, The Bluest Eye. Students in the seminar asked some fascinating questions about how Morrison read and narrated her own novel.

Emma: I can see how valuable such an exercise would be. It’s difficult to talk about the sounds of literary audio with the same critical precision we’re trained to employ in our discussions about written text. From what I gather, literary machine listening is a critical and neat tool, or practice, that assists in trimming our vocabulary by encouraging a certain self-reflexiveness in our engagement with audio. Such a creative, innovative, and intelligent approach seems to facilitate conversations and research into sound, and into sound as literature. I’m curious about other pedagogical tactics: what are some approaches to teaching audio in fiction/literature in the classroom? How do students respond?

Jentery: I have taught ten or so audio courses across the University of Washington and the University of Victoria. My experiences suggest students are eager to develop literacies for listening, which is also a gateway, if you will, into areas such as political phenomenology and media aesthetics. Who speaks for whom, how, and through which media? What values are at play in particular acts of hearing, listening, speaking, and gesturing? I also tend to use an array of audio formats to teach fiction: radio plays, recorded readings, voice-over, podcasts, audio drama, playable fiction, and games, for instance. I’ve never conducted a formal study, but my sense is that listening to audio across formats piques student interest in the range of fiction available to them while helping them to further develop their critical thinking, reading, and writing practices.

Among my favourite works to teach are Marina Kittaka’s Secrets Agent, Morrison’s audiobooks, Beckett’s radio plays, Stein’s readings of The Making of Americans, Delia Derbyshire’s compositions for the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, and Fullbright’s game, Gone Home. I teach these works in my undergraduate media and fiction courses at UVic, and they inspired my Fall 2020 graduate seminar, “Readers Are Listening,” where students composed some brilliant audio essays for podcasts of their own design. The private acoustic sphere of most audio work also appealed to me and many students at the time. It gave us a break from screens and zoomrooms and allowed us to multitask when we wanted or needed to. I listen to a lot of audio while going for walks and doing the dishes.

Faith Ryan, also in the Praxis Studio, has worked with me quite a bit on the pedagogy of audio, including literary audio. Her research on media and fiction is grounded in disability studies.

Faith: Thanks! Jentery’s “Readers Are Listening” seminar was really exciting for me as someone whose main interest is disability theory and media, and as someone who is also really interested in accessible instruction and course design. Fiction is not only textual, nor is text somehow a “better” or more valuable way to consume, learn from, and enjoy stories. I think the bias toward text still pervades English and Western culture. I often hear my friends say things like, “oh, well I only listened to that book,” as if listening is cheating or doesn’t count. Those sorts of assumptions reveal a cultural bias towards text that’s rooted in ableism. I’m excited about the possibilities of not only more learning devoted to audio in fiction, but also integrating the study of audio into the literature classroom with multimodal literacies in mind.

I was a TA for Jentery’s undergraduate course on “Contemporary Media and Fiction,” which focuses on developing literacies in audio, images, text, as well as play, and I really admire how the course is designed from the start to appeal to a variety of student learning styles and backgrounds. I’ve TA’d for this course twice, and each time the students are thrilled to be able to talk about content that feels relevant to them. Often, students already possess a lot of expertise in content such as games and podcasts, and it’s really exciting to have them share their knowledge and encourage them to think critically about the stories they engage on a daily basis.

Emma: We’ve been circling around the joy of sound and listening; what have you all been listening to? What sounds might we hear coming from the Praxis Studio?

Julie: I’ve been listening to Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower on audiobook, and I like to catch Allie Ward’s podcast Ologies here and there. In terms of music, recently I’ve fallen into a phase of listening to the sappiest ‘00s ballads—Lisa Loeb, Anna Nalick, Michelle Branch, and the like—I don’t know what that says about me.

For the Praxis Studio, most of the sounds we share these days are the doorbell chime on Zoom.

Jentery: Yes, lots of Zoom sounds right now. I’ve been listening to Waypoint Radio and all the Fanbyte podcasts, plus podcasts by students at UVic. I just finished listening to Morrison’s Beloved for my contemporary Am lit course, and I’ve been studying a bunch of radio plays from the mid-20th century. I like to listen to Beatrice Dillon’s Workaround while I’m writing. It’s ambient and yet not at all.

Faith: I am also listening to Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower. Right now, I am working on my MA project. It’s a podcast on sound in Alice Wong’s Disability Visibility Podcast, which has been my life-source during the pandemic. I also love to listen to Contra from the Critical Design Lab.

To keep up with the Praxis studio, check them out on Twitter!

Julie Funk is a PhD student in the Department of English and the CSPT program at UVic. She is also a member of the Praxis Studio for Comparative Media Studies. As a research assistant for SpokenWeb’s Pedagogy Taskforce, Julie’s interests are in developing tools and techniques for engaging in critical audio analysis without losing the contextualizing focus of audio’s inherent mediation.

Faith Ryan (she / her) is an MA student in English and a member of the Praxis Studio for Comparative Media Studies at the University of Victoria, where she researches disability justice, crip worldmaking, sound, and media.

Jentery Sayers (he / him) is an Associate Professor of English and Cultural, Social, and Political Thought at the University of Victoria, where he directs the Praxis Studio for Comparative Media Studies

This article is published as part of the Listening, Sound, Agency Forum which presents profiles, interviews, and other materials featuring the research and interests of future participants in the 2021 SpokenWeb symposium. This series of articles provides a space for dialogical and multimedia exchange on topics from the fields of literature and sound studies, and serves as a prelude to the live conference.