Decolonizing “Mayakovsky”: Listening to Listening

July 15, 2021

Clint Burnham, Deanna Fong, Linara Kolosov, and Teddie Brock

Clint Burnham, Deanna Fong, Linara Kolosov, and Teddie Brock

The following pieces expand upon oral responses given at the SpokenWeb event “From Reel to Reel: Animating the Archive” on February 11, 2021. The cultural object at the heart of this discussion was the poem “Mayakovsky,” performed by the Canadian avant-garde sound collective The Four Horsemen. The poem comes to us from the radiofreerainforest archive, housed at the Simon Fraser University Library’s Special Collection. It was played on the Co-op Radio show of that name on October 30, 1998 (the material history of this recording is detailed by Clint Burnham and Linara Kolosov below). The project of listening and responding to this recording begins with an invitation from Stó:lō scholar Dylan Robinson for Burnham to participate in a project-in-process on what he terms “listening positionality.” Here, Robinson invites artists, scholars, and musicians to record a short response to a sound recording of their choosing, guided by the following prompts: 1) Provide an account, a detailed description, of what you hear; 2) Provide an account of the impact of what you hear on your body, thoughts, and imagination; 3) Think through how what you describe above relates to your positionality (race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, cultural history, in any combination). Burnham’s response below speaks directly to these prompts, while the pieces that follow respond to his response, creating a layered articulation of recorded sound, listening, speaking, and writing. In making these responses available in written form, we invite further engagement with both the medium of writing and the medium of sound, as reader/listeners consider their own positionality vis à vis the histories, criticism, and methods described herein.

The original recording of “Mayakovsky” can be heard here; we invite you to listen to it before or during your reading.

Decolonizing “Mayakovsky”

Clint Burnham

I would like to describe what I am listening to, what I hear, in a recording of The Four Horsemen’s sound poem “Mayakovsky.” Active in the 1970s and 80s The Four Horsemen was a Canadian sound poetry group, whose members included Paul Dutton, Steve McCaffery, bpNichol, and Rafael Barreto-Rivera. This recording was played on the radiofreerainforest radio program, which ran on Vancouver’s Co-op radio in the 1980s and 1990s, hosted usually by Gerry Gilbert. In the fall of 2020, a digital archive of that program was made available through Simon Fraser University Library’s Digitized Collections, and the SpokenWeb group, and the work of Cole Mash and Linara Kolosov. I started listening to this recording one morning in October 2020, on my MacBrook Pro laptop. I at first had the sound coming out of my laptop’s built-in speakers, but I share a space with my partner and our college-age son, so I soon put on my AirPod earbuds to listen, as it were, privately. During the pandemic, everyone can hear everyone.

The poem “Mayakovsky” is bookended by Gerry Gilbert and Victor Coleman (both Canadian poets), first introducing the poem and then, afterwards, giving the Four Horsemen’s names. But the poem ends uncertainly, with the yelled

MAY-A-KOV-SKY!

but then a bit of silence, some breathing or panting, and another sibilant chant (what I first heard as “thea thea thea?”) and then another cut, followed by the sound of traffic. We hear the traffic because at that time, Co-op radio was housed in an old building above the BC Collateral pawn shop at the corner of Columbia and Hastings in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. Sounds from the street came into recordings willy nilly. In some ways that intrusion of traffic is similar to how the poem itself works: a minute and a half into the recording, when one of the poets is reciting “that all seems … now I am talking … now I am very interested in talking … everyone’s talking to someone, no one’s talking to no one” etc., suddenly one of the other poets screams

MAY-A-KOV-SKY!

and then the poets are chanting and doing breath sounds.

When I listen to the beginning of the poem, I try to pick out the four voices: a drumming, an “ayyyy-eee-uhh!” repeated at the beginning, then the voice talking while two voices chant and breathe behind it, the sudden explosion of

MAY-A-KOV-SKY!

repeated, yelled, breathed heavily, then a rhythmic chant again, so something that combines chant, breath work, words, and yells. And the range in volume, from quiet to conversational to declamatory to utter yelling, is part of how this piece works. Then, the variation of breathy sounds that feel embodied, to words that have meaning, to chants that carry rhythm, and then yells that bring volume. This is what I think is so cool about this piece, hearing four voices (and a drum? I don’t know), the liberation of yelling

MAY-A-KOV-SKY!

or of the throating, the voicing, the breathing, elongated sounds or syllables, the layering of these four voices. But also the crackling, the intro, how the place of the recording – radiofreerainforest, in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside – is also part of the work. For all that is taking place is heavily mediated, starting with me sitting here, listening and taking notes, listening to what is now a cut that was made with the Audacity software, so it’s now a file on my laptop, after downloading a 45 minute track from the SFU archive. (Note: when Teddie Brock asked me which file on the radiofreerainforest archive had the track, I couldn’t find it. For me that is the ideal sublime of the archive: you find something once, then you never can again, and you wonder if you made it up.) And that track was a digitization of a tape (analog) recording made in the 1990s, from Gerry Gilbert’s radio program on a community radio station, CFRO co-op radio, and that recording of “Mayakovsky” was itself played from the Four Horsemen’s 1977 vinyl LP, Live in the West, (which was actually recorded in Toronto), so the crackle is the needle on that record. What I was talking about a minute ago, about the poem “Mayakovsky” ending uncertainly, is because the record kept playing and we hear the beginning of the next track on Live in the West, a poem called “Assassin.” And I know this because I found the record (which I used to have on vinyl, as they say) on YouTube.

For me, hearing the Four Horsemen again is a moment of intense nostalgia and melancholy. (My inner psychoanalyst would say that nostalgia is always a defence against not having properly appreciated, or listened to, the Four Horsemen in the first place.) I heard them perform in the 1980s at Open Space gallery in Victoria. (I should say writing about hearing them is a moment of intense nostalgia and melancholy, for it is in writing the following that the floodgates really opened.) At around that time, 1986 or 1987, I interviewed bpNichol for the campus radio show Fine Lines at UVic (CFUV radio), and I wrote about bp’s work for my master’s thesis, working with Stephen Scobie. I have a cassette of that interview somewhere in my office (right here!), and I can remember cutting the interview on the editing deck, using a razorblade to make diagonal slices in the magnetic tape. The interview and part of my thesis were published in a collection edited by Roy Miki. In fall 1988 bp died – he was 44 years old. A decade or so later, I was a guest on Gerry Gilbert’s radio program a couple of times in the late 1990s when I lived in Vancouver (and Gerry published my first poem in his magazine BC Monthly in 1983, I think, when I was 21). I have those cassette tapes too. So my relation to these older avant-garde poets and academics was incredibly important, and also in a media sense, for my own formation as both a poet and a critic. In the 1980s, listening to and reading that poetry opened up ideas and practices for me about what writing and art could be. And then, here they are performing a poem about an earlier avant-garde figure, the great futurist poet, Vladimir Mayakovsky. Most, but not all, of these poets and scholars are white (Mayakovsky’s ethnic background was Cossack and Ukrainian and he was born in the Caucasus), and certainly the work of Deanna Fong, drawing on Timothy Yu, has alerted to me to how that white avant garde patrilineage should be troubled. But Mayakovsky’s name is what works here, pushing into the poem, perhaps a bit of Russian or Soviet exoticism, for sure, four syllables, like the traffic noise on the radio program recording, and coming out of the Four Horsemen’s bodies, entering, via computer bytes and wireless earbuds, our own bodies, bringing all that mediation with it.

(This is how I was listening to the poem, and what I offered to Dylan Robinson for a class he was assembling on listening practices. But Dylan turned it around, and asked me to think more about my own subjectivity, as a white settler listener, and questions of embodiment. So I added the following.)

What does it mean for me as a card-carrying member of settler postmodernism, to hear this? I talked about Russian or Soviet exoticism, but the drumming, chanting, breathwork, that all partakes of another exoticism, surely. So another listening might think, ok, it’s the intrusion of that settler avant-garde onto Indigenous sounds, except they’re more like the appropriation of those sounds (anyone who has heard the poet bill bissett with his rattle will know about the discomfort one feels, I’ve felt, or seen, in the “Eskimo chants” included in Vito Acconci and Bernadette Mayer’s 0-9 poetry anthology – Four Horsemen member Paul Dutton has credited the influence of Tuvan throat singing). But that’s not quite it either – for after that first yelling of Mayakovsky (three times in a row, actually), an interesting thing happens. You now have a series of breath works that do have that Inuit throat singing feel to them (not an expert, and have only seen/heard Laakkuluk Williamson-Bathory and Tanya Tagaq in person once, on October 28, 2016, at the Native Education Centre as part of the #callresponse exhibition at grunt gallery). It’s as though the Four Horsemen’s “Mayakovsky” is staging not so much a postmodern invasion but (or also) something that can be heard as sympathetic to or in solidarity with the “call and response” movement of Indigenous artists staging decolonization. I think the push-pull of my own resistance to locating or acknowledging or calling out this vexed question of postmodern appropriation might have something to do with my own settler heritage, wanting to be a good ally or comrade bumping up against growing up in a 60s scoop family (that is, my sister was adopted/scooped up into our family, from her Dene family in 1971). I can’t listen: what I am hearing is my own failure to listen (melancholy and nostalgia, again). I am not saying that if I listen to this recording, this sound poem, and hear the indigenous sounds – the appropriation of indigenous sounds – I am witness to postmodern colonialism. It’s the other way around : should I be listened to? Should Indigenous people listen to settler ruminations on these questions? Should I listen to my sister, or should she listen to me? Should Laakkuluk Williamson-Bathory or Tanya Tagaq listen to the Four Horsemen?

In an email I sent to Dylan Robinson in January 2021 I thanked him for pushing me. I am still trying to find ways of talking about the settler-colonial aspects of what I otherwise love (the Canadian avant-garde, Lacanian theory) and this was a good prompt. I’ve gone back & forth, for instance, in terms of how I think about bill bissett’s work. On the one hand, as a prairie kid in a military family in the 1970s, coming across his work (in a high school anthology!) was formational for me, and his appropriations of native chants, songs, drumming seemed like respect and/or honorable (this in the context, too, of living in Regina, a horribly racist place against indigenous people then, & seeing/hearing abuse directed at my Dene sister); Raymond Boisjoly recently reminded us on Instagram of Alcheringa, the 1970s magazine of “ethnopoetics” edited by Jerome Rothenberg and Dennis Tedlock, which sought to counter “cultural genocide” through “a place where tribal poetry can appear in English translation and can act (in the oldest and newest of poetic traditions) to change [people’s] minds and lives” (archived at Jacket2.org and PennSound). But then over the next twenty years, I tired of bissett’s work, and would leave performances he was doing that at (Western Front, late 90s). But then again, more recently, I kind of think well, he’s been doing it for such a long time now, you have to (I have to) respect the durational commitment. It’s not the same as some kid wearing a feather headdress at a music festival (and I do a fair amount of spoken word/rap, so who am I to say??). What would happen, what has already happened? It’s already too late, maybe you’ve heard this all before. Hear me out.

***

“It means that it means”: Vocalization and Desire

Deanna Fong

We can trace the roots of the genre of avant-garde sound poetry performed by the Four Horsemen to Zurich Dadaism at the turn of the 20th century, innovated by poets Hugo Ball, Tristan Tzara, Richard Huelsenbeck, and other performers at Zurich’s Cabaret Voltaire. In the critical writings from the era on the project of sound poetry, these practitioners outline their search for an Ur-language before meaning—before the cut of signification. They employ various strategies to put theory into action: Ball writes verse ohne worte, poems without words, in which we find free-floating signifiers that attach to nothing but their own sound. Huelsenbeck, for his part, composes bruitist poems in which noises themselves are the poems, taking no detours through linguistic signification. One of the overarching strategies that sound poetry uses to try and access this space before language is to appropriate the songs and poetry of African, Oceanic, and Indigenous peoples, using them as compositional material for sound poetry because the sounds—in their own mouths, at least—don’t make sense. They are used for sonic compositional practice, disconnected from the context of their production and, consequently, their spiritual and cultural significance.

While The Four Horsemen are not as overtly appropriative as the historical avant-garde that inspires them, in that they’re not extracting source material from other cultures, their work is nonetheless undercut with the same search for a primal language that is “before meaning.” That is, in the critical writings around the Four Horsemen, mostly initiated by members of the group themselves, sound poetry is rhetorically aligned with a fetishized Indigenous orality. In his book of essays, Prior to Meaning: The Protosemantic and Poetics, Steve McCaffery uses the term “paleotechnic” to describe the “territory of archaic and primitive poetries…syllabic mouthings and deliberate lexical distortions [that are] still evident among many North American, African, Asian, and Oceanic peoples” (2001). McCaffery proposes a stadial theory of experimental sound: “paleotechnic” is a sociohistorical designation that comes before Dadaist intervention at the turn of 20th century; it “ends” even though it continues on in the “lexical distortions” of Indigenous/orientalized peoples. However, “paleotechnic” is also used as an aesthetic designation meaning primal, libidinal, body-based, and “before meaning.” He claims that the Four Horsemen, despite falling into neither the temporal or geographical designations that he previously outlined, are also paleotechnic. In this subtle elision of history and aesthetics, he fetishizes the voices of cultural others as primal, keening, and, ultimately, lacking the sense of proper speech.

I want to offer some appreciation for the way that Clint’s audition of this piece grapples with its colonialist undertones without effacing its personal and affective significance for him as a subject pronounced through (barred by?) multiple and sometimes competing social forces. He gives special attention to the embodied presence of the poets’ voices, reading meaning not only in the symbolic form of language but also in the voice as signal: its volume, grain, timbre, and breath. As Mladen Dolar reminds us in A Voice and Nothing More, the voice has a meaning all of its own, above and beyond the symbolic message it carries: “it means that it means” (25). We can never disentangle language from its material support; the voice, and whatever comes out of our mouths—signifiers, grunts, or something in between, as with “Mayakovsky”—is both and neither at the same time, hence the voice’s status as partial object.

Above and beyond the materiality of the voice is the attention given to the materiality of medium and place: a meditation on how listening can be (and usually is) nested within different, competing scenarios of production and reception, both past and present. When we listen to this “Mayakovsky” we are at once in the Horsemen’s Toronto recording studio, Co-op Radio in Vancouver’s downtown eastside, Clint’s Mount Pleasant living room, or my dining room in Notre-Dame-de-Grâce, Montreal, as I listen to his listening. Here again, these multiple materialities are at once all present simultaneously, and yet the recording isn’t fully present in any one of them. The recording can always be articulated to new medial and geospatial vectors as the MP3 travels around: we played the recording for our SpokenWeb Podcast episode “Listening Ethically to the Spoken Word”, where it became inadvertently “stuck” to a few seconds of a recording of Dylan Thomas’ “Do Not Go Gentle into that Good Night” played at twice the speed (don’t ask), which happened to be the next track on my iTunes player. Media pick up this kind of situational debris as they circulate. This residue has meaning, even though it may not always be what we’re listening for. Lacan’s notion of “trashitas” (a portmanteau of “trash” and “caritas”), which we discuss in the podcast mentioned above, is relevant here: we listen not just for the manifest content on the tape, but also to the trash that it picks up along the path of its social circulation.

These multiple layers of material significance resonate with Clint’s approach to his own listening positionality. I was most struck by his précis of his personal connection with this poem and the particular literary historical lineage enfolded in the recording: hearing The Four Horsemen perform at Open Space Gallery in Victoria in the 1980s, his own participation in Gilbert’s radiofreerainforest program, his own interviews with bpNichol as a graduate student, and the complex publication history that ranges out from there. However, the constraints of the project for which this listening exercise was produced meant choosing between articulating positionality from a personal vantage (i.e. as an emerging Vancouver poet) and a political one (i.e. as a settler scholar). The 8-10 minute format meant that some discussion of the former positioning had to be cast off in favour of the latter—an important though nonetheless lossy sacrifice.

The complication at the heart of the matter here is: how do we negotiate the idea of positionality when our personal involvement with (we might say “libidinal investment in”) a work of art runs aground our positioning vis-à-vis structural forces of power? Yes, the personal is political but also there is a non-relation between the personal and the political, in that no subject is ever totally determined by their social positioning, and no measure of social codification (racing, gendering, etc) can ever account for subjects’ specific material experience. I’m here reminded of Danielle LaFrance’s poetic work-in-process #postdildo (forthcoming with Talonbooks 2022), in which the dildo stands in as a figure of relation, where she asks, “How can I tell if my desire is truly my desire and not capitalism’s injunction to enjoy what it wants me to enjoy in order to reproduce itself?” The minute we try to resolve this antagonism on one side or the other, we’re cooked. Reading these two readings of “Mayakovsky” together (personal, political) opens up a short-circuit between the singularity of the individual and the absolute form of structure (Robinson via Patrick Wolfe: “colonialism is a structure not an event” [HL, 27]) where otherwise no mediation is possible. Attention to the personal register of positionality is not to divert from the crucial project of Indigenous redress and resurgence that Robinson outlines in Hungry Listening—addressing the dominant settler-colonial modes of perception/audition, and centring Indigenous systems of knowledge, cultural forms, and relations. Rather, it gives us a way to confront complexity and antagonism within listening positionality itself, as cut with differences the professional, personal, familial, and libidinal difference. It allows us to approach what Robinson refers to as the “intersectional layering of positionality” (HL, 38), untrussing settler subjectivity as a homogenous formation by speaking to the other forces that shape perception and audition—some complicit, some oppositional, and some self-contradictory.

***

Listening to the Archive: Listening as a Part of Metadata Creation

Linara Kolosov

Different ways of listening are not limited to scholarly work. I want to talk about the metadata creation and the place and approaches to listening in it. The piece we’ve listened to is taken from the recently digitized radiofreerainforest collection processed by the SFU SpokenWeb team. The entire process of digitizing, creating metadata, and releasing the digital recordings of the 280 cassettes online took us about 10 months, taking into account that it was 2020.

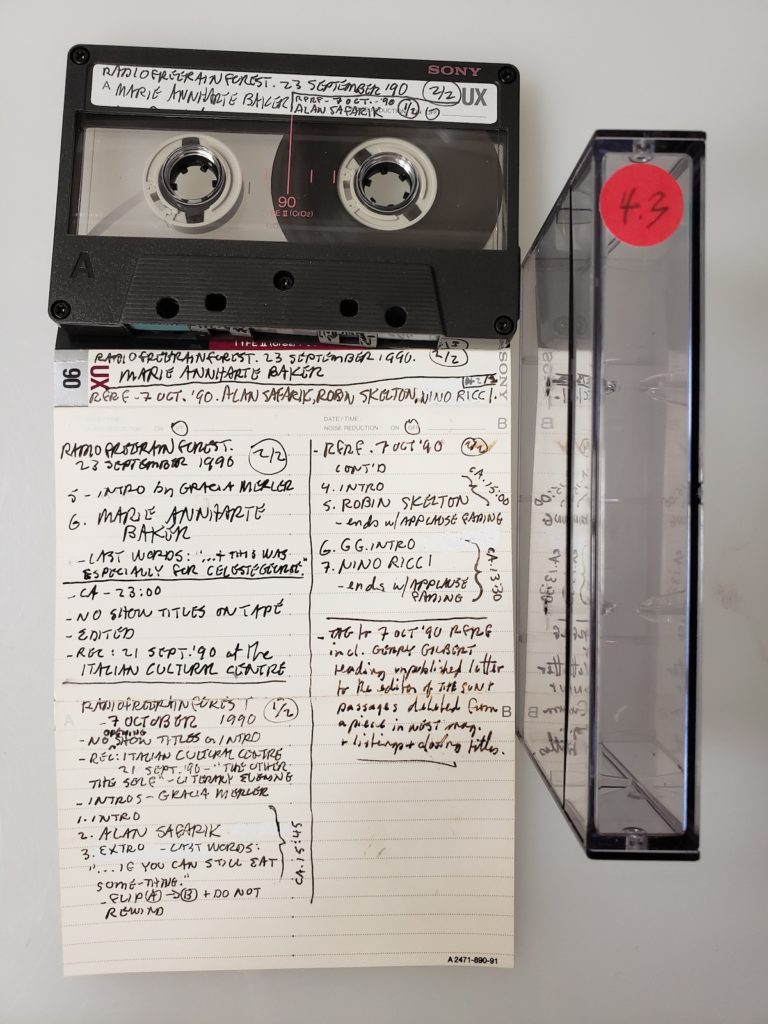

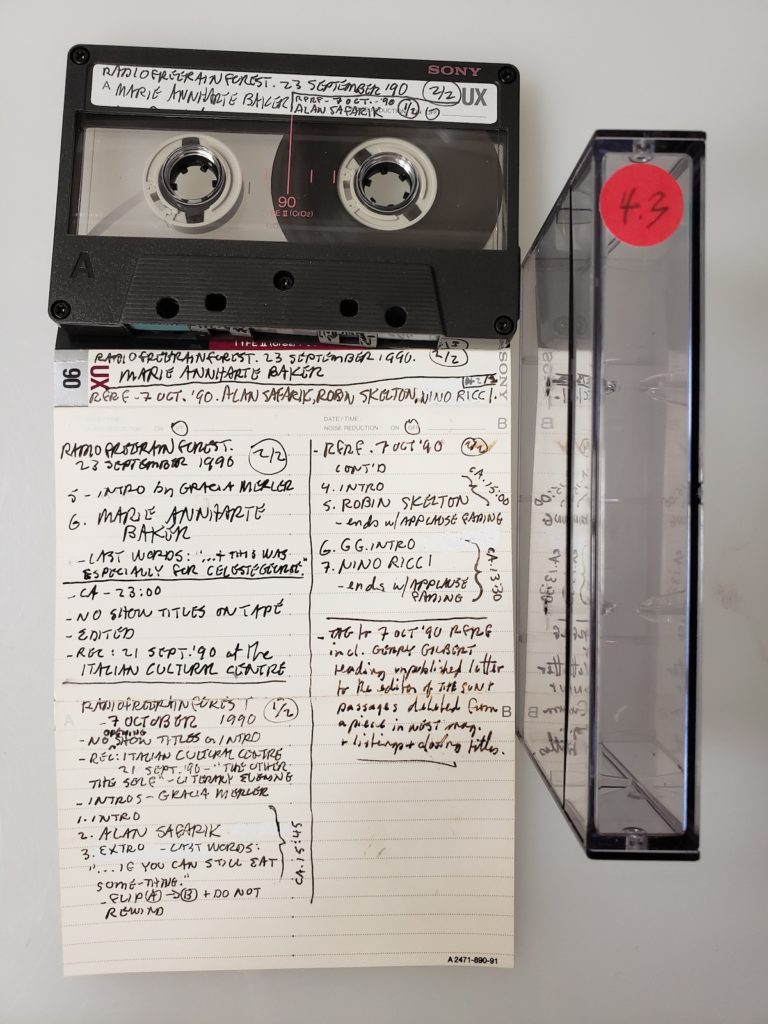

To create a digital collection, our RA team with the help of various librarians do the next steps: from the items in the fonds, we select the cassettes that need to be added to the digital collection. In most cases, we simply take all the audio recordings, however, for radiofreerainforest, we had to divide the radiofreerainforest cassettes from the rest of Gerry Gilbert’s collection that is much bigger and also quite messy, so it was not easy, and when we thought that we had all the cassettes already, we suddenly found about thirty additional cassettes and 12 reel-to-reels. After that, we prepare the individual items by marking them with red dots, assigning them a unique identification number, and then photographing each cassette. When all the cassettes are marked and photographed, the entire collection is sent for digitization.

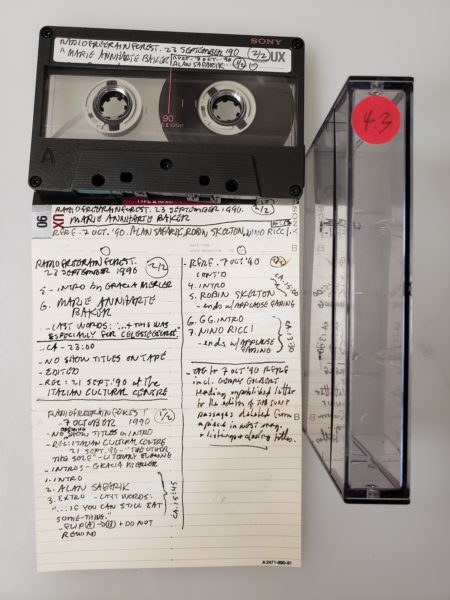

radiofreerainforest cassette tape and case from the Gerry Gilbert Fonds housed at SFU Special Collections

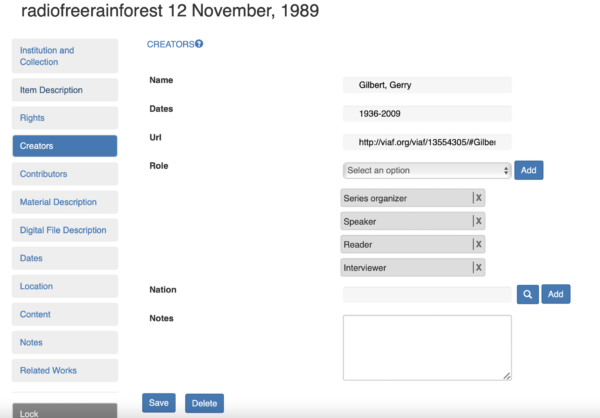

The fun part begins after we receive the digital files and start working on the collection processing, by which I mean listening to the cassettes, collecting information from the cassettes and j-cards, figuring out what kind of information is important to collect and what we, unfortunately, do not have time to do. To create meta-data, we use a unique SpokenWeb tool called Swallow that still undergoes upgrades and changes, so we learn to work with it on the go. We also often have to adapt and make some important decisions that may be crucial for future researchers. One of the hottest topics for us and the entire Spoken Web team for quite a while was about creators and contributors – we simply could not agree on who should be considered a creator and who should be a contributor. Is a person who records a cassette a creator or a contributor? Is the person who introduces a speaker a creator or a contributor? Or what should we do with people like Gerry Gilbert, who produces the show, introduces the readers, and often reads poetry during his show. What about when a person performs a poem by another poet, is the underlying poet a creator or contributor? As a result of these debates, our SFU team ended up entirely giving up contributors and making everyone creators. Such decisions are hard because we should do what we think makes the researchers work with the database easier and most productive, while also taking into account the decision of the entire SpokenWeb team.

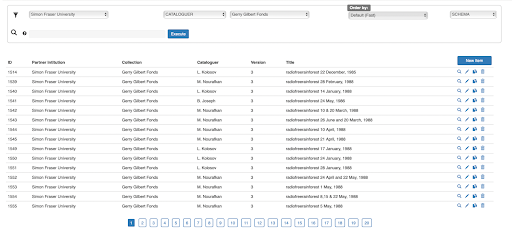

Screenshot of radiofreerainforest metadata entry in SWALLOW

Listening is, of course, another big part of our work. Because of the size of the SFU audio archive, which is about 2500-3000 cassettes, even if we had twenty RAs, we would not be able to listen to all our cassettes in their entirety. However, we still listen to parts of the recordings. We usually listen to the first few minutes, several random places in the middle, and a few minutes in the end. This technique helps us to understand the quality and the genre of the cassette, and check if the contents correlate with the information written on the cassette. These are the few pieces of information that we ranked as top ten important for future researchers. Having a list of the most important things we need to put into the database allows us to concentrate on the final goal of creating a digital archive, while still engaging with the collection. With radiofreerainforest, it was especially hard to stop listening to the entire cassettes, sometimes because Gerry Gilbert’s hard to read handwriting did not allow us to decipher the names of the artists, and more frequently, because this collection is unique in its weirdness and richness of the contents.

Cassette tape, case, and J-card from the Gerry Gilbert fonds

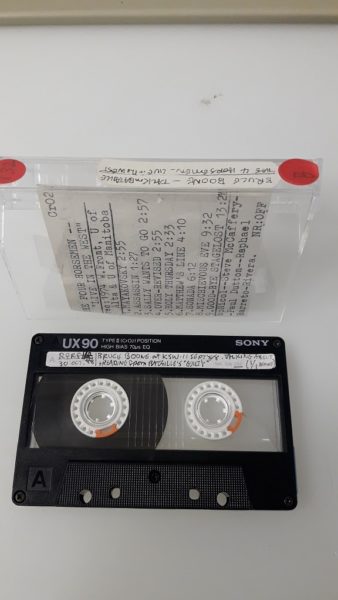

Reel-to-reel tape from the Gerry Gilbert Fonds

For some reason, my favourite part of each cassette was to listen to Gerry Gilbert advertising all the upcoming events of the week. I was fascinated by the number of readings they had on different venues and was dreaming about the day we could organize more readings of our own. I often listened to the entire poetry readings and interviews, which are my favourites. I find poets’ lives and their thoughts about writing unique because they speak in the moment without rewriting their thoughts and ideas, which means that they are more honest in some sense.

A list of audiotape metadata entries in SWALLOW

After all the entries are done, and each RA has edited their items, we go through the second round of editing. When everything is correct, the collection is ready for migration into the library platforms to be digitized and available to users.

***

Teddie Brock

I am struck by how the process of listening to Clint, Deanna, and Linara’s responses, in ‘real-time’ (although spatially dislocated), has encouraged me to reconsider my initial perspective in a way that I would not have been prompted to do in isolation. Over the past few months I have also spent more time listening to and learning about the history of the West Coast avant-garde poetry scene, including Gerry Gilbert’s work with the radiofreerainforest program, which has given me a more nuanced appreciation of the rich network of individuals and conditions animating these historical recordings. In this sense, I am grateful to have had the chance to engage with the archive in such layered ways that highlight the collaborative (and often unseen) labour that make public archives possible. Further, this process of drafting in terms of reading, writing, (re)-sounding/(re)-listening, across different contexts has drawn my attention to my own grappling with the complicated shifts and entanglements of my position in relation to the event, the archive, my personal history, and this overarching question of decolonial listening. That said, I view the reflection at hand, as well as my original piece, in more fluid, dynamic terms than their status of being inscribed in writing (along with my limits as a writer) might allow for.

At the same time, I remain curious about the ways these relational processes may potentially reveal how circulating emotions, as Sara Ahmed writes, do things as they align (or mis-align) bodily space with social space in ways that are both concrete and particular. In the immediate context of the event, and as a new graduate student, I intended to speculate about how academic and other institutional formations and their related social protocols may have worked to structure my own personal encounter (or others, by speculative extension) with the archive in more everyday ways. This more binary focus on structure in opposition to the individual, however, may also run the risk of oversimplifying the kinds of layers of affective complexity that were present in Clint’s reflexive positioning, for instance. The collective, dynamic aspects of the discussion and project has therefore pointed me to alternative avenues for reframing the more deterministic and reductive implications of my earlier position while still taking into account the ways these structures—although not static—may be economically or politically oriented toward the (un)-circulation of particular kinds of affectual responses informed by a politics of refusal—namely, positions that may reflect those of Indigenous scholars and writers such as Glen Coulthard, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, Eve Tuck, and Audra Simpson inside and outside the academy. Such positions highlight how the colonial “past” has not passed—nor has it been ‘archived’ as an historical event—but rather carries on as a present material structure, whether within the walls of the academic institution or outside of it.

Expanding (rather than moving away from) the positionality of individual listeners, then, Dylan Robinson suggests that it is also necessary to shift “the places, models, and structures of how we listen” as well as to question what might happen when we look beyond Western performance venues (or academic ones, in our particular case) to include “intimate spaces of one-on-one listening, spaces in relation to the land, spaces where audience members are not bound by the particular kinds of attention these spaces assert” (61). As Robinson points out, engaging with a process of listening otherwise also lends itself to flexible and improvisational movement toward wonder (and away from “hyper-vigilance” or Eve Sedgwick’s notion of “paranoid reading”) to reveal the limits of certainty and the drive for identification and cataloguing in order to acknowledge more fully the boundaries of knowability. Meanwhile, the material infrastructure of social listening spaces also remains pertinent as more of our networked connections have taken place online. Crucially, there is already a longstanding history of Indigenous engagement with digital infrastructure to resurgent ends, as Marisa Duarte (Arizona State University) addresses in Network Sovereignty: Building the Internet Across Indian Country, a perspective that adds necessary nuance to a position, replicated in part by the original piece I presented below, which often presumes an degree of antagonism between digital technologies and decolonization.

Listening to Listening: Layers of Mediation and the Four Horsemen’s “Mayakovsky”

To frame my own listening of the Four Horsemen piece, I wanted to consider Clint’s statement about hearing his own failure to listen and where this leads us, or fails to lead us in a discussion of decolonial approaches to listening. I would like to foreground Dylan Robinson’s framing of “hungry listening” which describes a settler orientation toward listening that aims to isolate and capture what is being listened to. By this logic, sound is experienced first as something uncontrolled, undisciplined. Sound in itself is not experienced as “valuable” beyond its role as potential information. Listening is the tool that “settles” sound into boxes of certainty and resolution, discrete units that circulate smoothly in settler economies. As the dominant mode of sensory engagement with sound, “hungry listening” instructs us to ignore the contexts that frame our listening, without which these modes of listening would be impossible. These frames, processes, protocols, rituals are invisibilized as hungry listening fixes our attention on content to the exclusion of other possible meanings and ways of being in relation to the world.

In 1961, R. Murray Schafer speaks about the composer—particularly one who is white and Western— needing to “wring his material” in order to make Inuit song “musically presentable” for the audience he imagines would be listening to his work. But this statement precludes even the existence of other audiences (and non-audiences). “Presentability” here is the objective fact that settles a border between music and undisciplined sound and obscures the ongoing processes of sensory settlement that worked to establish the notion of a “presentable” default. Is “presentability,” then, the given aesthetic starting point for the Four Horsemen? As an experimental work, is the intended effect of the piece also deeply invested in this foundation in order to ‘disrupt’ it?

I am wondering now about my own ability or inability to listen to the Four Horsemen as a part of a relational, institutional, and technical situation. My first encounter with the piece has been mediated by an account of nostalgia for this artist community, and then a reflection on the possible meanings settling or unsettling into that nostalgia. In listening to the piece for the purposes of an academic talk, it is also difficult to shake my trained desire for a kind of ‘settled’ argument that hides the traces of ambiguity and uncertainty from a final product. The institutional risk inherent to a process of listening in such a way (even to one’s failure to listen) is that it will present a barrier to academic analysis, productivity, or efficiency, revealing instead a fraught state of relationship.

Part of our invisible listening context for the Four Horsemen piece also includes the fleeting temporality of pre-internet radio, as well as the audio that comes before and after it, because this event today is constrained by time. In the full-length program, leading up to when the piece is aired, there is a discussion of names that we should know, names to keep note of, to the exclusion of absent or invisible others, not only in this moment, but which serves a practical function we have come to recognize as central to radio shows and podcasts. The broadcasters mention a “study centre” that may or may not be named in memory of bpNichol of the Four Horsemen. The fact of bpNichol’s value to Canada’s poetic avant-garde, reinforced to us by both the radiofreerainforest‘s and bpNichol’s presence in a university archive is a cultural force that perhaps limits the space for listening otherwise to the piece, muting the kind of affective response that would contradict the cultural mood and values being conveyed to us, starting from the first moment of hungry listening during the Four Horsemen’s writing and performance of the sound poem in the 1980s, to the presentation of academic meaning generated from it years later.

In listening to the piece, my own perceptive bias influences my need to make sense of the English words spoken on the track. “Mayakovsky,” I think, assumes the frustration of a listener trying to hear English in order to make meaning out of this experience. In the background, the work has circulated to us through processes of archival labour and protocols, as a historical document digitized into an MP3, a format rooted in a history of telephone research defined by technical and cultural practices that privilege the hearing of non-tonal over tonal languages. Research that was shaped by the American Telephone & Telegraph Company (AT&T’s) need to cram as many phone-calls into their telephone lines as they could in the early twentieth century, positing the neat separation between meaning and auditory perception. How might we account for these similarly invisible, yet persistent layers that frame our encounters with art through a decolonial listening practice toward a literary archive? Martin Daughtry’s approach to listening as “palimpsestual” suggests we orient ourselves toward discerning “both the things that a recording encourages us to remember and the things it urges us to forget, the things that are insistently audible and the things that have long been silenced” (62). Building from Dylan Robinson’s call for strategies to “re-format” and “de-format” norms embedded in Western music venues, I wonder about how to also account for the seemingly banal elements that permeate our remote listening environments. To approach familiar formats—both technical and social—not as universal defaults but as contingent practices animated by corporate monopolies, the subjects of laboratory listening tests, along with the discursive rules that shape the kinds of questions we might ask about what it means to speak, to communicate, or listen otherwise to the art we (which consists of particular ‘we’s’ not a universal ‘we’) make, celebrate, archive, and become haunted by.

***

Bibliography

Ahmed, Sara. “Affective Economies.” Social Text, vol. 22, no. 2, 2004, pp. 117–139.

Ahmed, Sara. The Cultural Politics of Emotion. Edinburgh UP, 2014.

Compton, Wayde. “Race Literacy ‘Anti-racist Poetics’ by Wayde Compton.” YouTube, uploaded by Black Canadian Scholars Series, March 1, 2017.

Coultard, Glen. Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition. U of Washington P, 2014.

Dolar, Mladen. A Voice and Nothing More. Short Circuits Series. Ed. Slavoj Žižek. Cambridge, MA and London, UK: The MIT Press, 2006

Duarte, Marisa Elena. Network Sovereignty: Building the Internet Across Indian Country. U of Washington P, 2017.

Grande, Sandy. “Refusing the University.” Toward What Justice: Describing Diverse Dreams of Justice in Education, edited by Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang. Routledge, 2018, pp. 147–65.

Harney, Stefano, and Fred Moten. The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study. Minor Compositions, 2013.

McCaffery, Steve. Prior to Meaning: The Protosemantic and Poetics. Evanston, IL: Northwestern UP, 2001.

Robinson, Dylan. Hungry Listening. U of Minnesota P, 2020.

Sedgwick, Eve “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, or You’re So Paranoid You Probably Think This Essay Is About You,” Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity. Duke UP, 2003.

Simpson, Audra. Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life across the Borders of Settler States. Duke UP, 2014.

Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake. As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance. U of Minnesota P, 2017.

Sterne, Jonathan. MP3: The Meaning of a Format. Duke UP, 2012.

Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, vol. 1, no. 1, 2012.