Ghost Readings are durational, performative, and collective practices of listening. The story of how their methods evolved – and exactly when the ghost entered – is a long story, or rather a series of stories, intertwined with the early years of SpokenWeb and with SpokenWeb’s series of events called “Performing the Archive.” Let’s begin with the durational, performative, and collective dimensions of this listening practice, specifically the question of what we are doing when we listen. How do we as literary scholars tend to listen to literary audio from the past? Often we listen to a clip from a recording rather than to the recording in its entirety. This partial listening is often due to practicality and time constraints, but it is also rooted in our pedagogical familiarity with assignments based on close reading. For example, students might be asked to listen to a recording of Phyllis Webb reading “Rilke” in the Sir George Williams University (SGWU) Reading Series recording from 1966 and to compare it with a print version in Wilson’s Bowl (1980). That type of assignment is one that I have assigned and has generated terrific analyses, but it need not be the predominant way of engaging with literary audio. What if the experience were durational and even informed by practices of re-enacting the recorded event? For instance, we rarely listen to an entire recording, or at least not usually with others. By entire recording I mean not only playing the full recording but also listening to its media history as an object of recording technology. What would happen if the recording was listened to in its entirety? And listened to in its entirety by a group of people rather than a solitary listening in one’s headphones?

When you listen together, listening changes. Collective listening to recordings in their entirety, near or on the same day when the reading would have taken place, has been a practice developed by the Concordia SpokenWeb team. We have called this practice a Ghost Reading.[1] A group of listeners gathered to listen to a recording in its entirety, or at least in full as it was recorded since some recordings end before the end of the reading. In our case, the dates we chose to hold the Ghost Readings were significant as, in most cases, the reading was held on the same date as when the reading took place. For example, Muriel Rukeyser read at SGWU on January 24, 1969 and we listened to Rukeyser’s reading on January 24, 2019, exactly 50 years after the original reading took place. The audio selected for the Ghost Readings so far has been audio archived as part of the Sir George Williams Poetry Series, 1966-1974. The reasons for this are partly due to convenience – this series was the first SpokenWeb audio collection digitized and made accessible online – but also it allowed for a consideration of what it would have been like to listen to the Canadian and American poets who read in that series right here at Concordia University, which was then called Sir George Williams. Many of the readings took place in the same buildings where we hold our classes and, while some of the spaces have changed, the aura of place remains. The place is significant, but more on that after telling the story of the Ghost Reading itself.

Over the course of the first Ghost Readings, we started to notice how we ourselves as listeners in the Ghost Reading became performers as well as practitioners of listening. Why and how? It was partly due to the fact that we were recording the events, but it was also due to the extent to which we were reflecting on how we were undertaking our listening. Collective listening can be participatory performance art. There is something performative in gathering to play the role of listeners and agreeing to the terms of a reading in which the “readers” are played on a recorded medium. If one may have arrived at the reading wondering what is the purpose of gathering to listen to something that one could just as easily listen to on their own, they were soon met with the reality that this listening is not necessarily about the content, though of course it is part of it. Rather than it being solely about the content (i.e. what we will listen to), this kind of collective listening is about the practice of listening (how we are listening). The value in listening to audio together has informed SpokenWeb Listening Practices that began in the year following the Ghost Readings and very much as an extension of them in order to explore methods of listening across disciplines in more detail. In fact, the early events that evolved into the Ghost Reading were described as “poetry listenings.” Listening Practices deserve another history of their evolution, but, for now, back to the ghost.

A Short History of The Ghost Reading

[Katherine McLeod]: The Ghost Reading Series that is starting today is the first [sound] of the official series but it’s not the first ghost reading that has taken place – we’ve been haunted by these recordings before. [Laughter in room.] You may remember that a couple years ago I gathered some of us to listen to the Gwendolyn MacEwen and Phyllis Webb reading, and there was another instance in which we listened to the Robert Creeley reading. These are all opportunities to think about what we are actually listening to when we’re listening to this recording. And to listen to the recording in its entirety. Today we’re listening to a recording that was made of poet Ted Berrigan reading at what was then Sir George Williams University on December 4, 1970… [fade out].]

— Transcription of the above audio recorded, from the first Ghost Reading (or was it the first?)

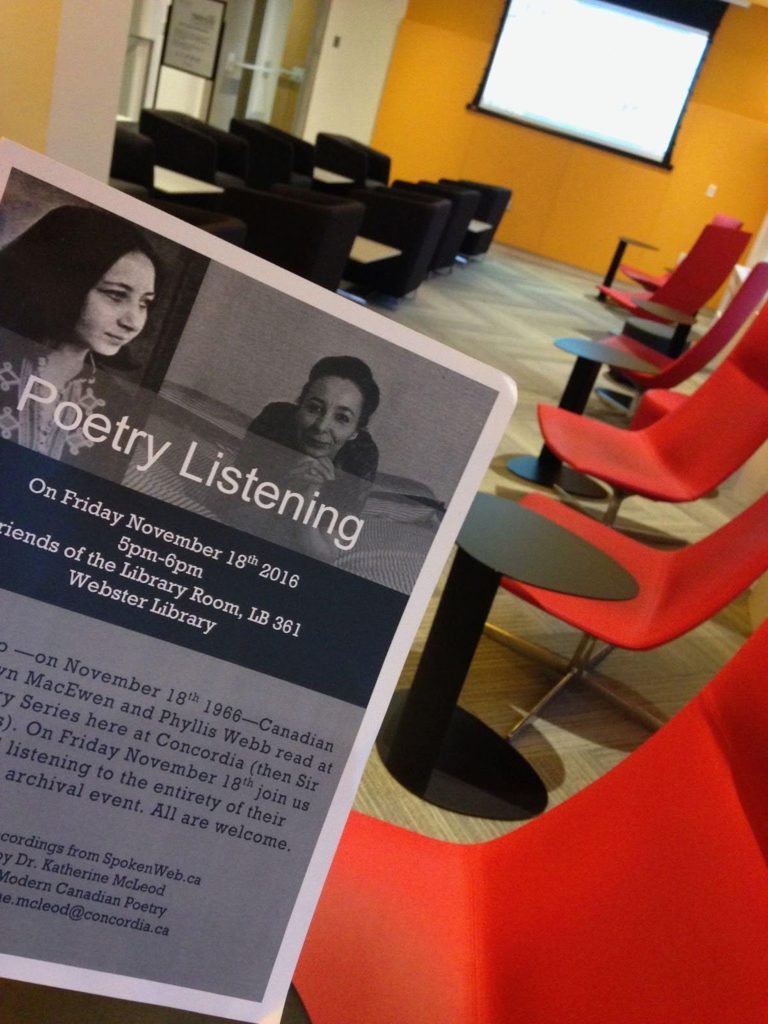

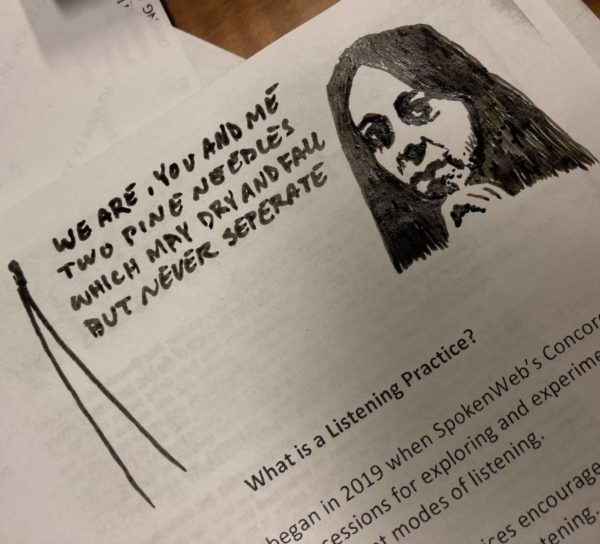

The Ghost Reading, as a practice, did not begin as a Ghost Reading. On 18 November 2016, I held what I called a Poetry Listening in which my undergraduate students gathered to listen to a recording of Gwendolyn MacEwen and Phyllis Webb. It was exactly 50 years since their reading was recorded in Montreal on 18 November 1967. The attention to the date – exactly 50 years after – and the choice to play the entire recording in order to experience what it would have been like to hear Webb’s entire reading. That reading was then followed by MacEwen’s entire reading, and listening to it all allowed us to re-enact what it would have felt like to be a listener in the room with Webb and MacEwen in 1966.

Waiting for the listeners to arrive (Concordia U), 18 Nov 2016.

That 2016 Poetry Listening was held in the Friends of the Library Room in Concordia’s Webster Library, and proved to be a perfect space for listening with its comfortable chairs, windows to the city, and sound-proof walls. Having held that Poetry Listening with the recording of Webb and MacEwen, I was invited to curate a Poetry Listening for “The Literary Audio Symposium” (Concordia, 2-5 December 2016), which was held in the same Friends of the Library Room. For that listening, we listened to the entire Robert Creeley reading from the SGWU Poetry Series.[2] That listening was a small group of listeners, but the seeds of the Ghost Reading had begun because there was something that caught our attention from the fact that we were listening to a recording in its entirety and that we were doing so together. That collectivity continues to inform SpokenWeb’s Listening Practices. In the fall of 2019, Concordia’s SpokenWeb team began holding biweekly Listening Practices, which were informal gatherings for communal listening. Listening Practices took on a life of their own that continued online during the pandemic, but their roots in the value of communal listening go back to the Ghost Reading. So how did the Ghost Reading become the Ghost Reading?

Enter The Ghost

The “first” ghost readings were not called Ghost Readings but rather they were called Poetry Listenings. What inspired the change in name? What called for the entrance of the ghost? In the fall of 2018, when I was discussing with Jason Camlot the format of holding a series of poetry listenings to recordings in their entirety (like the listenings to MacEwen & Webb and Creeley), we came to the idea that holding the listening on the same date that it would have happened was, to some extent, an attempt to re-enact it. That re-enactment was appealing. Plus, the idea of a poet being haunted “by their past selves” was already in the language used to describe the types of archival-based poetry listening that SpokenWeb had held, such as the one with Daphne Marlatt and Diane Wakoski in 2014.

Daphne Marlatt on stage listening to a recording of her own voice at Performing the Archive, 21 Nov 2014

In a Ghost Reading, it would not be a poet performing with their past self but rather the recording would be the performer. I would not have realized it at the time, but looking back, that transition to the recording technology-as-performer is when the ghost entered the scene (though it had been ever-present from offstage throughout). Looking back at the description of the Ghost Reading Series that Camlot and I wrote: “The term ‘ghost’ used to describe this series refers to the voice that speaks in the present from the past through electronic archival media technologies. Scholarship, for example Jeffrey Sconce’s Haunted Media, has noted the historical preoccupation with connections between electronic media and spiritual phenomena” (“SpokenWeb Concordia Has Launched Ghost Reading Series,” 1 Dec 2018). The “ghost” in the Ghost Reading was intended to be the ghostly media through which we access the audio. This is important too because sometimes participants have talked about how the phrase Ghost Reading suggests that the readers are no longer alive, but in fact some of them are, which makes it all the more important to remember that it is the reader’s “past voice” haunting the experience of the recording, just as much as it is the uncanniness of the technology that allows us to re-experience it. This kind of ghostliness became a mode of performance itself in some of the SpokenWeb Performing the Archive events that pre-dated the Ghost Readings, wherein a reader heard in an archival recording would return to the venue of that original reading and read again alongside their archival self. Imagine George Bowering, or David McFadden, or Daphne Marlatt, standing on stage, having just read a poem, now at the podium listening to themselves read at this same venue fifty years earlier. In this example, the past voice of the poet haunts the living poet as a public performance of listening.

What does the uncanniness resulting from a voice of the past haunting the present sound like? Sometimes it may be nearly inaudible and more conceptual (in knowing that you are listening to a recording of the past), but other times it loudly intervenes: for instance, in the recording of Nichol and Kearns the tape distortion is a story of its own.

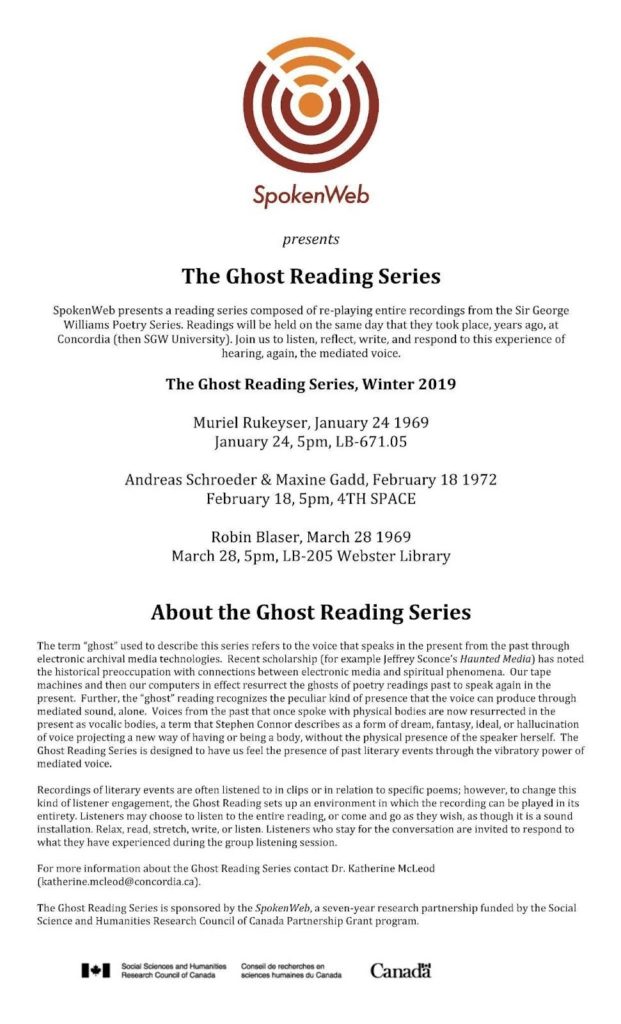

In the language that Camlot and I used to describe the Ghost Readings of 2018-19, our choice to frame it as a reading series was intentional in that it allowed for a durational investigation into this practice of listening. After the Ghost Readings with the recordings of James Wright and Ted Berrigan in the Fall of 2018, we decided to design a poster for the upcoming readings, which also included the full description of the Ghost Reading as a theoretical and performative practice.

Poster for the winter lineup for The Ghost Reading Series, 2018-19

Listening as Making

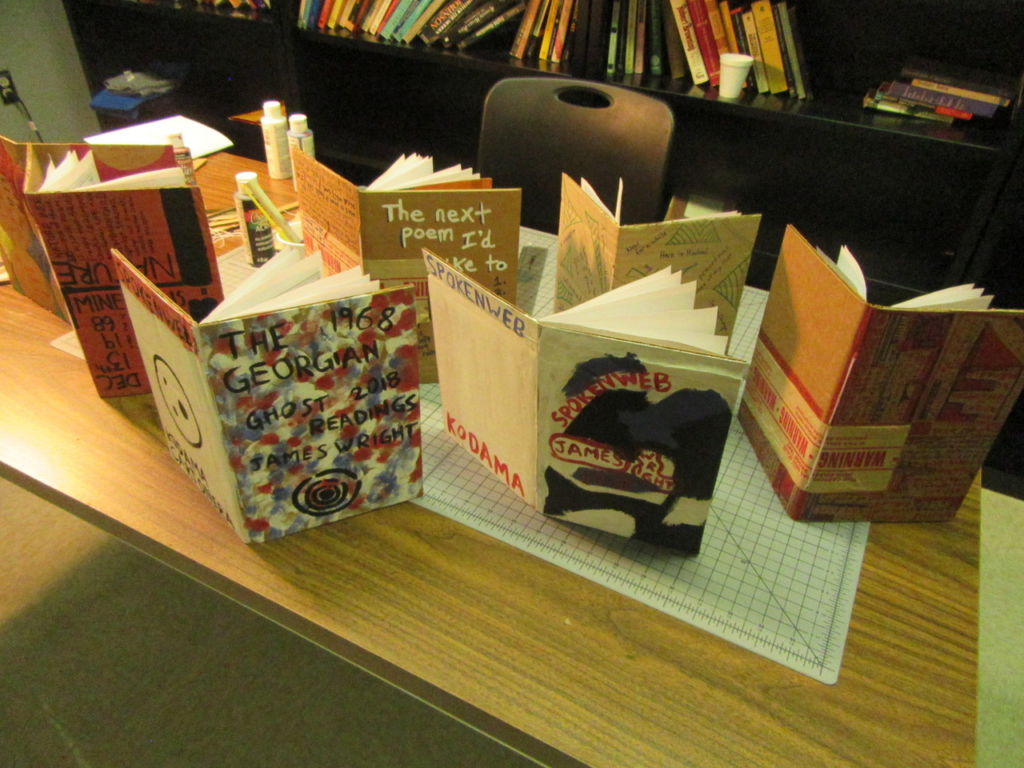

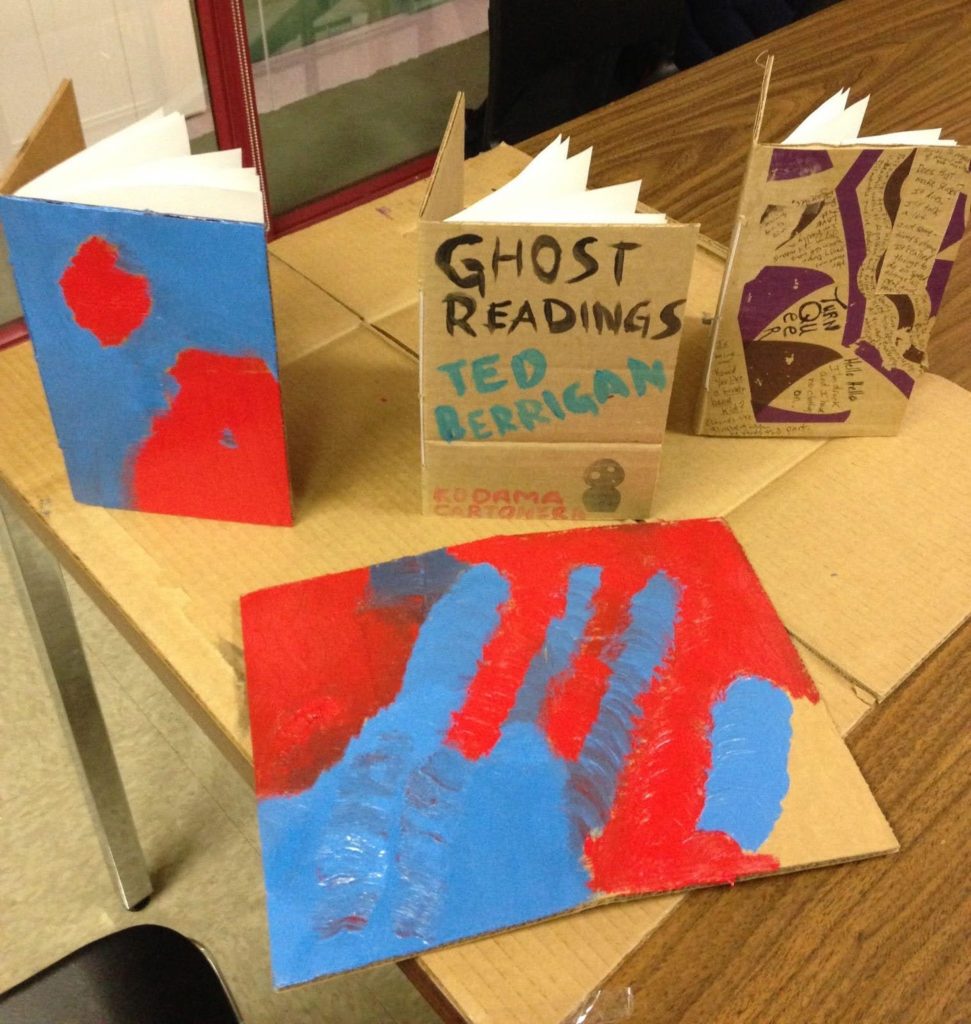

Ghost Readings are about and enact practices of listening, but they are also about and enact practices of listening as making. What did we make? Well, when listening, we likely would have taken notes anyways, but the act of making something new with our notes, doodles, drawings was formalized at the Berrigan Ghost Reading when PhD student and SpokenWeb collaborator Aurerlio Meza suggested setting up a Kodema Cartonera book-making table. Books would be made with ephemeral materials related to the recording. Meza printed out copies of The Georgian, a student newspaper that had advertised the Berrigan reading, and Meza quietly taught us how to make books while listening.[3] Some of us started to make art, and we started bringing a variety of art supplies to the Ghost Readings. We ended up keeping the artwork as records of our listening too.

Photo of books and art made throughout the 2018-2019 series.

During the Ghost Readings, the spaces where we listened became laboratories of making-as-listening. We started in Concordia’s AmpLab (prior to its renovations into The AMP Lab), and we explored holding the Ghost Readings in a few other spaces such as 4th SPACE and a classroom in Concordia’s Webster Library.

Robin Blaser Ghost Reading in the Webster Library, Concordia (2019)

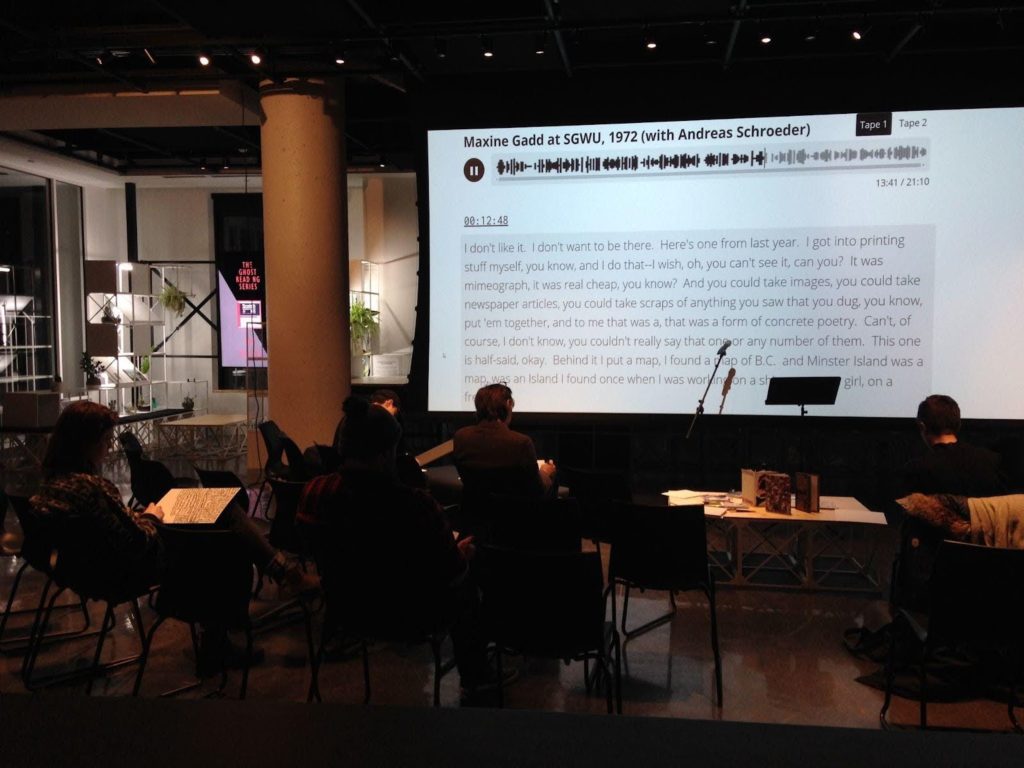

Maxine Gadd & Andreas Schroeder Ghost Reading in 4th SPACE, Concordia (2019)

The various acts of making that would take place in the Ghost Reading all related to recording, in one way or another. We would make something new with the traces – the transcriptions, the drawings, the doodles. The book-making was one form of that, but we also started keeping multiple types of materials “made” during a Ghost Reading. It was like keeping a tactile recording, which was not a sound recording but that documented the sonic experience in other formats. At the time, Camlot was in the midst of intense discussions about transcriptions, description and metadata for the hundreds of hours of literary audio that were starting to be catalogued in those early days of the SpokenWeb partnership. Ghost Readings were a way to reflect on how we were listening to the extent that our listening was a form of creative transcription, a record of what we heard. In each Ghost Reading, we continued to practice listening-as-making, whether booking-making, note taking, drawing, or crafting. We made more art. And since then, these tactile records of the Ghost Readings have proved to be the most useful forms of documentation, functioning as creative transcripts/metadata of what we heard and perhaps even best representing what the Ghost Reading itself was as a series of events.

Practice / Performance

A Ghost Reading is an act of listening to literary audio, but it is also a practice of paying attention to how you are listening. We were making-as-listening – and we were talking. We were talking about how we were listening and what we were listening to, and these critical debriefings became one of the most important parts of the Ghost Readings as practice. Halfway through each reading, we paused. In the conversations that took place, we discussed what surprised us, moved us, what we noticed about the voice, about the sounds of the recording, what we imagined the reading to have been like, and what we found ourselves attending to in our present-day space and in our listening bodies.

That clip of the critical debrief includes sounds of our ongoing book-making while talking, along with our speculation about how the technical side of the audio was captured, or not, by the recording technician (“what was he listening to” and “was he even there?!”). Did we think about ourselves being recorded as we spoke? As someone who was in the room and was part of the conversation, I would say yes and no. The recording device was visibly present in the room with us but we spoke candidly and as though it wasn’t there.

We Recorded It All

At the Ghost Readings we were listening, making, and talking—and recording. We recorded it all. Audio recordings have been made of each reading, including the full playing of the original recording and the conversations afterward. Imagine that fifty years in the future, a student opens up the recording of the SpokenWeb Ghost Reading Series, 2018-2019, and listens. What are they listening to? I have been arguing that the Ghost Reading Series constitutes a practice of listening. But, in recording, does that practice become performance? (Or only if someone decides to listen to the recording?) The Ghost Readings as a series exists along a continuum of various types of Performing the Archive events that have been organized through SpokenWeb during its early phases and as a partnership. Often those events have involved a poet listening to a recording of a past reading on stage, and in those cases they were performing their listening for a public audience. But, in those first Ghost Readings, were participants performing or practising listening? I would say that they were practising, but the fact that they are recorded does create the possibility of this listening practice becoming a performance. Yet, how readable – or discernible – is the performance for future listeners? What would a future listener be able to discern by listening to a recording of a Ghost Reading? Even more than hearing what we were listening to, they would be able to hear (or at least try to hear) the room, the sociality, the art-making, the book making, and our conversations about our listening. Those sounds would be our performance, and no matter how those sounds would be interpreted there is the potential for a future listener to listen to our listening.

Ghostly Affordances – Making and Unmaking

As the 2019 series came to a close, I was reflecting on its form for a paper I was presenting at the first SpokenWeb Symposium at SFU, and I could not help but consider the limitations of the Ghost Reading. I was aware that I had become enamoured with the format of the Ghost Reading, as were many of the participants. After all, it was an affecting experience and our enthusiasm was palpable. Ghost Readings were a joy! And I could also tell that I was close enough to the experience of them that it was time to pause and ask: What else can the Ghost Reading do as a performance and as a critical intervention in literary audio archives? And what are its limits?

The Ghost Reading is an event designed to be a safe and collective encounter with what can be most uncomfortable and unsettling in the archives.[4] The ghostliness of the archives. Calling it a “ghost” reading brings a mysterious allure to it, but, at the same time, ghostliness has negative associations of uncanniness and fear that seem at odds with an event defined by an ethics of care. Does that mean, then, that a Ghost Reading also can engage and even activate those negative feelings? Before diving into what can be most uncanny, and even scary, about Ghost Readings, I would say that, as opposed to listening alone, a Ghost Reading does present a potentially care-full environment in which to talk about the affective messiness of archival audio. For example, if one hears racist or misogynistic audio when listening alone to archival audio, it can feel deeply uncomfortable, as it does in a group, but in a group one can at least try to not be haunted by questions such as: Has anyone else noticed that while listening to this recording? What should I do about the fact that I am, for example, digitizing and cataloguing this recording for SpokenWeb’s collection? Should this recording be flagged? Or should I pretend that I didn’t hear it? But how can I forget? When listening together, the uncomfortableness is still there, but there is the potential as a listener-performer with agency to intervene in the haunting of the archive and to talk about it – and back to it. There is the potential to say, I heard that too! There is the potential to debrief during and afterwards, and there is power in being able to collectively call out unsettling audio.

But can the archive be held accountable? During discussions in and around Ghost Readings in the years since they took place, I started to wonder if the Ghost Reading as a format holds the archival recording in a reverence such that it can be hard to speak back to it. By suggesting this, I do not mean that there is no possibility for resistant listening within a Ghost Reading but more that the format can create an aura around the recording, which then a listening could actively disrupt – but will it? When I think back to what it felt like to be there in the Ghost Readings of 2018-2019, it is important to remember that it did not feel like we had given up control to the “ghost” of the recording. We did pause, stop, talk over, speak back to the recordings in our own ways, and collectively when we discussed them. I think what changed for me was in teaching the Ghost Reading (coming up in the next section of this article) and in reflecting on the force of the phrase “Ghost Reading” for those who see the title without having experienced it. In other words, how the “Ghost Reading” is read rather than how it is experienced. I asked Camlot how he remembers it:

…I felt we were all at work, in parallel, in kind of dismantling the recording as it unspooled, and that time was moving us not only towards the end of the recording, but even more importantly, toward a period of sharing our acts of listening resistance and reflections on our own listening patterns, to the point that the content of the recording (what is held in reverence in your account of it) was quite secondary in the discussion and sharing to what we learned about our own approaches to listening.

When I think back on those Ghost Reading practices I see us as a bunch of little listening elves crafting models of our experience of listening, soon to be shared in a show and tell with each other…

That description beautifully conveys the affective experience of being part of those Ghost Readings in 2018-2019, and I was grateful to be transported back in time after so much thinking about the resonances of “ghost reading” since then while trying to work through what exactly constitutes the haunting.

I came to realize that what was haunting me was not related to the practice of the Ghost Reading (which I continue to feel can be a joy-full and care-full sonic practice), but it was related to the fact that the Ghost Reading asks one to contend with the ghostliness of archives as they have been shaped by colonial and patriarchal logics. What, then, in the case of literary audio archives constitutes the “ghost” as that which is absent in the archives? Or unspoken? There but not heard? These kinds of questions made me want the Ghost Reading as a format to do more, even though it was already becoming a practice of resistant listening.

Further critical context for listening as resistance is work by Stó꞉lō musicologist Dylan Robinson in Hungry Listening: Resonant Theory for Indigenous Sound Studies (2020) and sonic enactments of resistant listening as performed by artists such as Wolastoqiyik musician Jeremy Dutcher and Nisga’a poet Jordan Abel. In the case of the Ghost Reading as resistant listening practice, the act of bringing sound recordings out of the archives and listening to them collectively is not enough to constitute decolonial listening, but doing so is one step towards then considering ethical methods of working with archival sound recordings, which can then lead to what decolonial listening sounds like. That is important because the location of the Ghost Reading Series as developed at Canadian universities raises the question of how the terms ghost and reading resonate in a literary soundscape haunted by settler colonialism. To historicize the ghostly in CanLit, one could point to the oft-anthologized poem by Earle Birney – “it’s only by our lack of ghosts / we’re haunted” – or one could look to the work of Marlene Goldman on representations of haunting in Canadian fiction (DisPossession: Haunting in Canadian Fiction, 2012). But what comes to mind, to me, most urgently is the way in which colonial haunting manifests sonically in writing by Billy-Ray Belcourt, Liz Howard, katherina vermette, Eden Robinson, Deanna Reder, Daniel Heath Justice, and again Dylan Robinson. If I were writing another article on all of this that goes beyond the story of the Ghost Reading as a practice and toward ghost reading as a critical concept, these are the writers through which I would turn to to listen for the resonance of the ghostly. Haunting is not only a metaphor, but it is the lived experience of loss and a denial of joy and futurity, whether that be individual loss for personal reasons or collective loss as a direct or indirect result of colonialism in Canada as a settler state.

While writing this article as a story of Ghost Readings, I saw a call for papers for ASAP/Review on haunting in the contemporary arts, and the language used in that call is exactly the kind of pressure on the Ghost Reading as a form that I hope readers will consider too:

Avery Gordon’s Ghostly Matters, Christina Sharpe’s In The Wake, Esther Peeran’s The Spectral Metaphor, David L. Eng and Shinhee Han’s Racial Melancholia, and several works by Fred Moten and Stefano Harney bear collective witness to a broader critical turn—or return—to the haunt as a subject of animating, or at least un-dead, interest. How should we come to terms with the experience of haunting, and what can it tell us about the arts of the present […] What is the relationship of haunting to other forms of lingering or “present” absence, as inscribed at the heart of traumatic histories of racial or sexual violence? How do different media or art forms haunt each other, and haunt us? [“Cluster Call for Papers: Hauntings”]

As gestured to in this call and in the framing of collective listenings as performative re-enactments earlier in this article, a critical direction for Ghost Readings could be performance studies, and there are more.[5] The Ghost Reading as haunted by its own invocation of ghostliness in the context of settler colonialism does not mean that the format should be disbanded, but rather that future versions of the Ghost Reading could encounter this past through multitudinous ways of listening, both in the listening that takes place at the event and in the listening to the format itself by curators, participants, and critics writing and thinking about it afterwards. One such direction is disentangling the remediated histories of cultural performances in Canada, for which, as Eve Tuck and C. Ree remind us, “[s]ocial life, settler colonialism, and haunting are inextricably bound; each ensures there are always more ghosts to return” (“A Glossary of Haunting”). Talking about the practices through which one listens to archival recordings seems like a necessary place through which to think through this haunting. The Ghost Reading has only begun, and much more can be made from its invocation of haunting. After all, a Ghost Reading is not only about listening but also about making – or, more accurately, making and unmaking.

Asemic writing from listening by Jason Camlot.

The Ghost Reading Returns – Sound Pedagogies

Ghost Readings had to be paused during the pandemic. But they have started again. Not as a series but as one-off events. Last fall I was teaching a class on Contemporary Canadian Poetry at Concordia and I had already integrated archival recordings of poets Daphne Marlatt, Phyllis Webb, Dionne Brand, and Fred Wah into the syllabus, and I noticed that one of the recordings from the SGW Poetry Series landed on the day of the class: bpNichol and Lionel Kearns, recorded on 20 November 1967. I thought I would integrate a Ghost Reading into my class on that exact date. That date is important because it was when we almost had the first Ghost Reading. Wait, when?

That’s right. When I said that the first Ghost Reading was the recording of Berrigan, that statement was not entirely accurate. After the Poetry Listenings, the first Ghost Reading was intended to be this Nichol and Kearns recording, and Jason Camlot and I had coordinated it with Karis Shearer and the UBCO AMP Lab so that they would be listening at the same time as the Concordia team. Incidentally, a note of connection back to the Creeley Poetry Listening: Shearer had been at the Creeley listening and we had talked about wanting to recreate that type of event again, along with UBCO holding their own Poetry Listenings as part of their programming.

However, as the November date approached, Shearer and I both realized that November was too packed to try to hold this Ghost Reading, and we decided to cancel. But, even though the event was cancelled, we both listened to part of the Nichol and Kearns recording: I was at home and Shearer was with her students in the lab, and we messaged back and forth about how much the recording made an impression. There were intriguing sounds (the tape has distortion), memorable poems, and also deeply unsettling content that made us uncomfortable and shocked. Here were two prolific and revered poets, but there was also politically incorrect language and outright objectification of the female body in numerous poems on the recording. For context, this is the same recording that has Nichol reciting his poem, “The True Eventual Story of Billy the Kid,” which had drawn the ire of Canada’s parliament when it won the Governor General’s award in 1970, but this was not the poem that made us pause, cringe, and check-in with how we were feeling while listening. I tell this story of our uncomfortable listening because it sets up the listening that then took place in the Ghost Reading of 2023. Yes, I selected this recording knowing that it was not an easy one, but I thought that what would be most productive would be that we could – finally – listen together and try to grapple with its complexities. And November arrived, and we did.

After holding the Ghost Reading in my classes, I was elated that the Ghost Reading had returned. We had listened together to the recording in its entirety, we had paused to discuss what we were listening to, how we were listening, we took notes, we moved in the space while listening, and even looked at the artwork of past Ghost Readings – and yet I was left feeling like there was something about bringing the Ghost Reading back that felt different than that first series of readings in 2018-2019. In that first series, I left feeling joyous and inspired, and I did this time too but the extent to which there was an accountability for the archives was haunting me.

What was different? Was it more that I was aware of the Ghost Reading as a form when teaching it than when participating in it? When we were participating in it in 2018-2019 we were also developing it as a practice while doing it. Maybe that was it. In my class, I started the Ghost Reading with a short history of the Ghost Reading, and then we dove into the recording. Would it have been better to do that separately and then let the Ghost Reading stand on its own? Or was it the time that had passed from 2018-19 and perhaps my nostalgia for those pre-pandemic years? I think it is all of these things. Had Ghost Readings reached their limits? No, rather, the experience of bringing the Ghost Reading back made me realize that the Ghost Reading was haunting itself.

There is a performative history of the Ghost Reading and, yes, that does haunt each iteration of it, but that can become part of what makes it continue to evolve. The experience of a Ghost Reading need not be overly concerned with learning about what was done in the past but rather about what kind of making and listening is taking place here and now in this experience of it. Furthermore, I would argue that the Ghost Reading calls for a closer consideration of the curatorial control of the archive. What I mean here is the extent to which the archive has curatorial control of itself. For example, that recording of Nichol and Kearns took over the sound and space of the room once it was playing. As curator of the event, I chose the recording, but because I let it play in its entirety it took on its own curatorial power once it was playing. What are the affordances of that power as archival audio? And how does one interrogate that power, specifically the power of archival audio, which has been preserved and to some extent been given value simply by the fact that it has been kept? How does archival audio call for a different mode of ethical care rooted in critical listening? Those are the questions that emerged, for me, from the Ghost Reading in November 2023, and in many ways they speak to what was always there in the first iterations and my interest in pushing back against the format towards the end of 2019.

With distance we can bring more criticality to the Ghost Reading. As I was starting to articulate in the previous section, more attention to what function haunting has in the replaying of a recording is one step towards this criticality, along with curatorial work in situating the recording context of the listening, both in terms of its history and its present resonance. We can implement practices of past Ghost Readings in future ones, and we can also strive to make and to listen to the Ghost Reading in the time and space of its performance. For me as a curator of Ghost Readings I felt this most acutely when the participants were my students. The curation of the Ghost Reading was intersecting with the curation of the classroom.[6] I had curated what we had heard in that space thus far and so when students expressed discomfort during the Ghost Reading that made me rethink the ways in which sound holds power over a space, even when that sound is from the past.

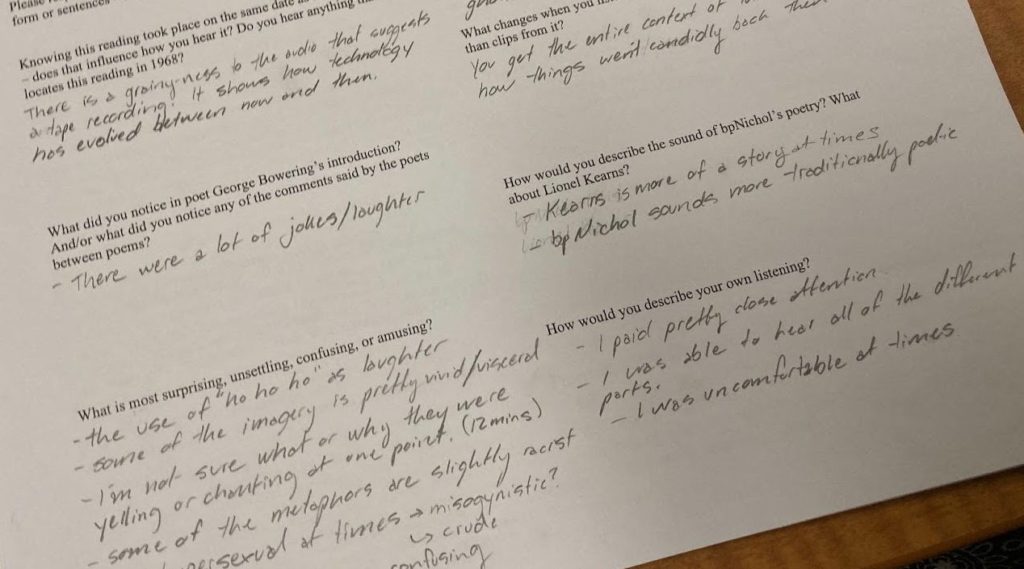

An example of student notes during the listening to Nichol and Kearns.

While the pedagogical and performative have always overlapped in the Ghost Reading, I do think that holding this Ghost Reading in a class changed the extent to which the “ghost” took control, and the extent to which participants had willingly or unwillingly agreed to that ghost as present in the room. The Ghost Reading was haunting the Ghost Reading. I wanted to teach them about the history of the Ghost Reading, as a format for archival listening,[7] while also undertaking an entirely unique Ghost Reading experience of hearing the Nichol and Kearns recording. And, to an extent both of these things did happen, but it was interesting to realize how many other “hauntings” were also taking place, intentionally or unintentionally.

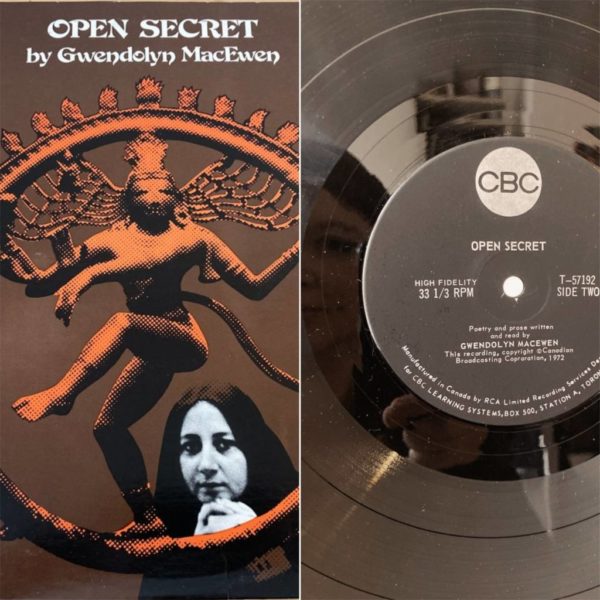

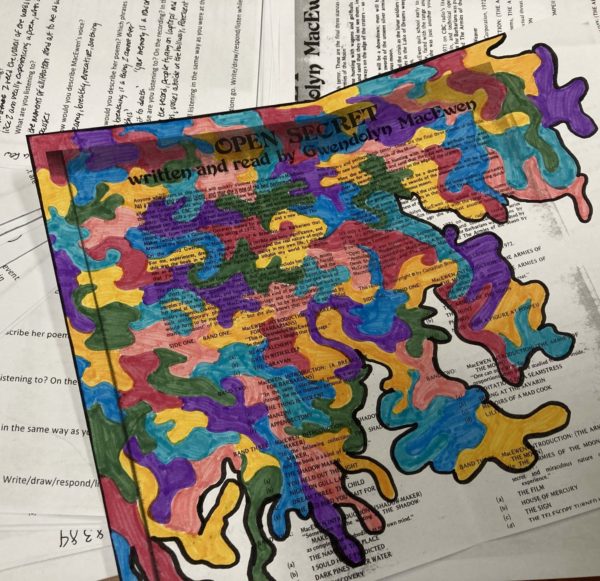

What further draws attention to the myriad of affordances for teaching the Ghost Reading is to compare it to another approach to curating archival listening in the classroom. This last “ghost” story in this article combines the Poetry Listening as a collective listening with SpokenWeb’s Listening Practice as an opportunity to reflect on how we are listening. In Fall 2022, I was teaching ENGL 379 Contemporary Canadian Poetry at Concordia and I held a Poetry Listening in that class on 19 October 2022, both for the class and open to the public. I was about to go on maternity leave, or more accurately was about to give birth at the end of that month, and I wanted to pay homage to the Poetry Listening to Phyllis Webb and Gwendolyn MacEwen that had taken place in my class in 2016. I also wanted to bring a recent archival find into the classroom: a vinyl recording of Gwendolyn MacEwen reading, Open Secrets (CBC Learning Systems, 1972). With the help of a portable record player from SpokenWeb’s AMP Lab, I brought the archival voice of the poet into the classroom and we thought about the medium through which we were listening.

Images used to share the classroom Listening Practice and student responses to listening.

This poetry listening wasn’t durational, and I didn’t call it a Ghost Reading because I was not trying to re-stage that exact type of listening practice. I called it a SpokenWeb Listening Practice intentionally as a way of teaching that method of archival listening along with the poetry and voice of MacEwen. Nevertheless, it was ghostly in its own (beautiful) way, and it was also a reminder that there are a multitude of ways to practice archival listening, both inside and outside of the classroom.

Future Ghosts

The Ghost Reading will continue to be a method of listening collectively. To undertake a Ghost Reading will be to engage in practices of listening and to be aware of oneself as a performer of this listening. As Ghost Readings take place in the future, within or outside of SpokenWeb, they will develop this haunted form in new ways and that development will depend upon the listeners-as-participants. What is clear from how the Ghost Reading has developed is that participants in a Ghost Reading play a larger role than we ever could have imagined. Listeners are performers, even if they do not fully realize it at the start. We might start our participation in a Ghost Reading by thinking of ourselves as quietly listening to an archival recording, but we too are part of the performance. What are we performing? Our listening. And, if our listening is recorded – which, of course, it has been – a replaying of that recording would not only replay the archival source material but also any audible traces of our presence while listening.

Listening to a recording of a Ghost Reading is listening to listening. Will a SpokenWeb researcher, one day in the future, press play on one of these recordings of a Ghost Reading and listen to our past listenings?

Only time will tell.

*

ENDNOTES

[1] This article is a revised and expanded version of a paper that I delivered at Resonant Practices in Communities of Sound (SpokenWeb Symposium at SFU, May 2019). The conversation that followed the papers was recorded, thereby creating another listening to this listening. My paper was also in dialogue with a short talk on collective listening that I delivered on the plenary panel, “Listening,” for that same symposium. Since then, thank you to Jason Camlot, Klara du Plessis, and Emily Stuchbery for their thoughtful listenings to this article as it has evolved.

[2] Listen to Jason Wiens talk about this Poetry Listening in the episode “The SpokenWeb Symposia Retrospective: Celebrating Sound Studies” of The SpokenWeb Podcast: “I remember one of the first events I attended—sort of pre‑SpokenWeb, when we were gathering to prepare that initial SSHRC Partnership Grant application. We had a listening party where we all went up to a room in the Tower at Concordia and listened to a Robert Creeley recording from the Sir George Williams Series on a Friday night. That was quite a memorable moment.” [0:07:01]

[3] The book-making with ephemera from past literary events spilled out into non-Ghost Reading performances such as when Ian Ferrier had invited SpokenWeb to perform at the monthly Words & Music show at Casa del Popolo in December 2018. Meza set up a book-making table at that performance too with ephemeral materials relating to the archival recordings that McLeod and Camlot used to create a remix for their collaborative performance that night (which ended up being the start of another kind of embodied and musical practice of performing the archive), and the book making was underway during the solo performances that took place by Klara du Plessis and Jason Camlot. Ghost Readings had begun productively haunting other forms of archival performance.

[4] The location of the Ghost Reading Series at a Canadian university raises the question of how the terms ghost and reading resonate in a literary soundscape that has largely defined listening as performed in a settler colonial context.

[5] Fast forward to this term and, while reading Kristin Moriah and Rinaldo Walcott in preparation to teach Mary Ann Shadd Cary, I am struck by Walcott’s invocation of ghostliness, along with his reference to Avery’s Ghostly Matters. For Walcott, even while Shadd Cary “remains the kind of ghost we should want to travel with (33),” the story of Black studies in Canada is “a story of haunting and its many ghosts, of how the shadowy figure of Blackness lurks or haunts Canadianness, understood as whiteness, and what kinds of effort must be accomplished to render this haunting unimportant, and further whether we can break through this haunting if our past remains a largely silent one” (“The Struggle to Emerge” in Insensible of Boundaries: Studies in Mary Ann Shadd Cary [2025], ed. Kristin Moriah). Haunting serves as a reminder for how much history is yet to be heard.

[6] My thanks to Ghost Reading attendee Klara du Plessis for reading a draft of this article and for adding a useful comment that there are additional structural conditions of the classroom to consider: “I wonder how the set duration of a class could interfere with the durational nature of a Ghost Reading, especially in terms of also making time for interruptions and debriefing.”

[7] For more on archival listening see “Archival Listening” by Katherine McLeod in ESC: English Studies in Canada, vol. 46 no. 2, 2020, p. 325-331.