ShortCuts: TAKE 2 – ‘Little Magazines’ and New Print Possibilities in Canada

August 14, 2023

Teddie Brock

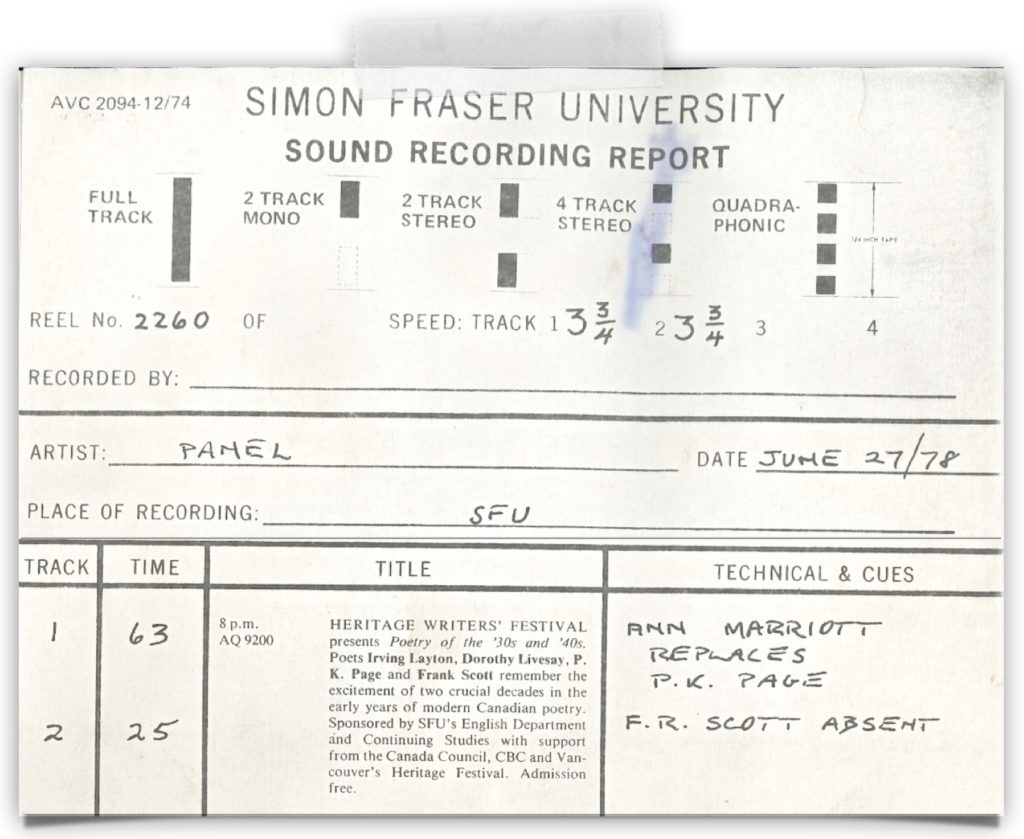

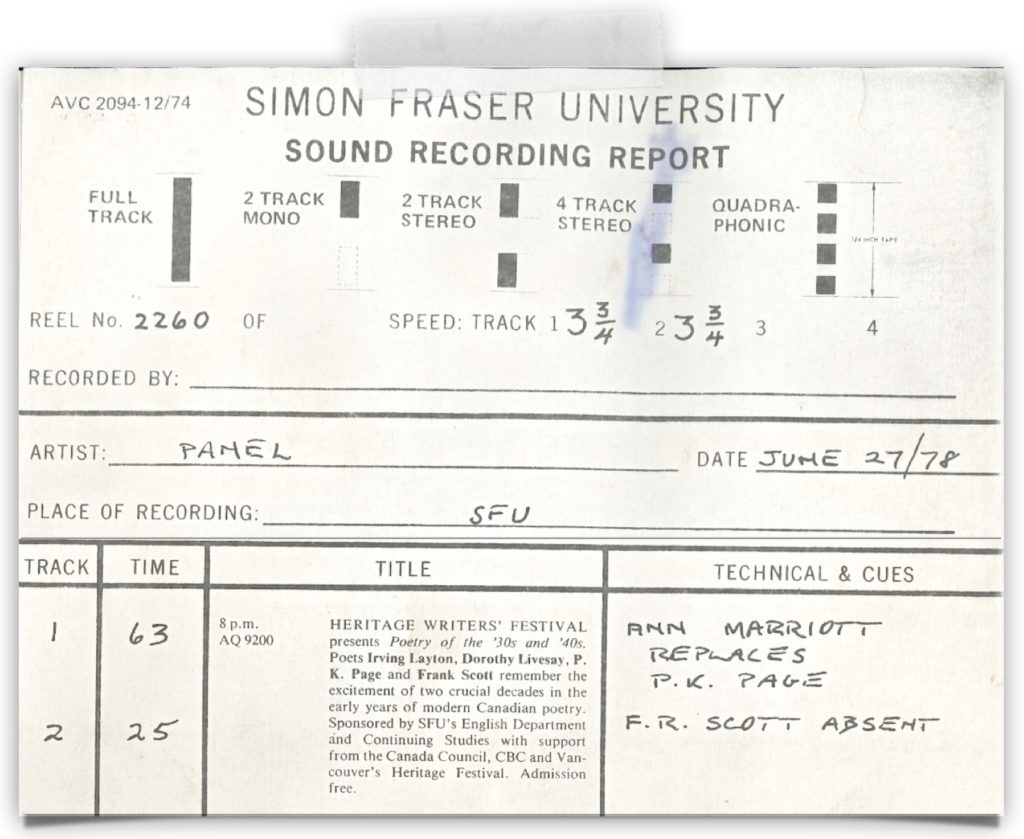

This post is the second of a three-part series by Teddie Brock, all based on a 1978 panel discussion with Dorothy Livesay, Anne Marriott, and Irving Layton, as recorded on audio preserved at the Simon Fraser University Archives. Check back on SPOKENWEBLOG for the next installment of this close listening to the archives as they roll out over the coming weeks.

Clip 01 – 38:42-39:08 (OBJ-287_SideA)

LAYTON: “So I went through the university without ever hearing of T.S. Eliot. And of course when I was in high school, not only did I not hear of any important English poetry, but I never heard of Canadian poets, like Lampman, or Duncan Campbell Scott, or Charles G. D. Roberts. I was brought up with the notion that to be a poet you had to be either English or dead—or both!”

Clip 02 – 14:48-19:08 (OBJ-287_SideB)

Marriott & Livesay During Q&A

MARRIOTT (15:36-16:03): “Well, I think poets now are really very lucky. As Dorothy and Irving have said, it was really hard to get published. I often wonder if “The Wind Our Enemy” would even have got published if Dorothy’s father hadn’t taken it and been a good friend of Lorne Pierce, and I know it got a lot of publicity, it was reviewed all across the country, because Dorothy’s father was head of Canadian Press.

MARRIOTT (16:04 – 16:26): “… and now I think with these grants and all the little magazines —I mean now there are just so many magazines, it’s just absolutely marvelous, there are so many places to get published… and, there are no sort-of—…”

LIVESAY CUTS IN: “Well, is that a good thing in your opinion?”

MARRIOTT: “Oh, yes I think it is a most excellent thing, I mean why not?”

In these clips, Irving Layton and Anne Marriott discuss the invisibility of Canadian poetry and its emergence through the “little magazines,” non-commercial periodicals that facilitated the transmission of innovative modernist poetry throughout Canada in the 1930s and 1940s. Reflecting on his experiences as a student at Baron Byng High School in Montreal, and later as a university student at Macdonald College (now known as McGill University) in the 1930s, Layton read neither the British modernists like T. S. Eliot nor the writings of late 19th and early 20th century Canadian poets such as Archibald Lampman, Duncan Campbell Scott, or Sir Charles G. D. Roberts at the time. Although the school curriculum had introduced Layton to poets such as Wordsworth, Byron, Shelley, and Tennyson, it was in part through his literary relationships with Louis Dudek, Patrick Anderson, and John Sutherland that he became more invested in the innovations of both American and British poets, including E. E. Cummings, Walt Whitman, Hart Crane, Dylan Thomas, W. H. Auden, and Stephen Spender, as well as Rainer Maria Rilke from Austria, and Stefan George from Germany. Layton’s reflections on the importance of these formative poetic encounters highlight how little magazine culture in Montreal emerged in the 1940s to address the disconnect between the colonial-leaning politics of academic curricula, which elevated canonical British poets, and the wave of modernist literary movements that were taking place in Canada, the United States and Europe.

While two of these Montreal-based little magazines, First Statement (1942-5) and Preview (1942-5) had initially different perspectives concerning the ideal trajectory for modernist verse in Canada, together they shared the vision of breaking away from the traditionalist and nationalistic tendencies that had so far characterized mainstream Canadian literary culture. Founded by the poet John Sutherland, First Statement emphasized the need to establish a Canadian literature that could be uniquely its own rather than continue to be “a parasite” on other cultures (SFU recording). Along with the poet Louis Dudek, Layton later joined the magazine’s editorial board to support a platform for articulating the urban social reality as he experienced it in Montreal, free of the restraints he felt were imposed by the pervasive “gentility” that “separated culture from reality” (SFU recording). Outside the academy, it was also through First Statement’s editor, John Sutherland and his sister Betty Sutherland, that Layton was first exposed to the modern verse being circulated outside of Canada, particularly from Britain, including the work of T. S. Eliot and W. H. Auden.

While First Statement focused on American influences such as Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams, Preview, whose editorial board included the poets F. R. Scott, and, later P. K. Page and A. M. Klein, were more interested in the British modernist lineage of poets such as T. S. Eliot and W. B. Yeats. Although both magazines were deeply invested in shaping the direction of Canadian poetry in opposition to the traditionalist ‘old guard,’ Preview’s British cosmopolitanist leanings were often viewed as comparatively more exclusionary and conventional by those poets associated with the First Statement group. In the midst of ongoing philosophical tensions, eventually the editorial boards of both magazines merged to create The Northern Review, which ran from 1945–1956.

What can be heard in Layton’s retrospective commentary in 1978, then, is the extent to which his introduction and later involvement with little magazine culture in Montreal in the 1940s helped broaden his awareness of the possibilities for a distinctly modern Canadian poetry, written by Canadian poets, and aimed at Canadian audiences. In contrast to what Layton perceived as the less progressive culture of literary academicism, Layton’s literary activity throughout the 1940s in the pages of Montreal little magazines lay the groundwork for his infamous outspoken and rebellious poetics, while also allowing him to explore the philosophical questions that preoccupied him in light of the second World War.

In the second clip, Anne Marriott can be heard answering a question during the Q&A period from a member of the audience. The question concerns what has changed in the literary conditions for Canadian poets in the 1970s. Compared to the time of recording in 1978, the three panelists depict the 1930s and 1940s as periods when writers appeared to rally together in the midst of the nation’s shared social struggles: the immediate threats of the Great Depression, the Spanish Civil War, and later the Second World War, as well as the economic and political difficulties they faced in being published and building a sustained readership. In response, Marriott reflects upon the relative challenges for writers during the 1930s, framed by her own circumstances under which her poem “The Wind Our Enemy” was first published with the help of Livesay’s father and Lorne Pierce, editor of the historically prestigious Ryerson Press. Acknowledging her relatively privileged and contingent position in the Canadian literary scene, Marriott sounds celebratory as she describes the dramatic increase of small presses that had emerged since 1957 with the creation of the Canada Council for the Arts. Throughout the event Livesay and Marriott often speak to the barriers to publishing and running magazines in the absence of the national funding opportunities that, by 1978, had been already embedded in the literary landscape. For instance, both poets bring up the necessity for perseverance and resourceful approaches to networking and engaging with powerful literary connections, highlighting a tension between the communist and socialist politics of many small-press magazines, including Masses (1932–34) and New Frontier (1936–37), and their frequent reliance on, as Livesay recalls during the panel discussion, the “capitalist money” of their various donors (SFU recording).

But the challenges for writers trying to get their work published in the 1930s and 1940s were not strictly financial. Frustrated with the lack of interest in modern poetry by the mainstream magazines that had since dominated Canadian literary culture, which had long been plagued by masculinist, anti-bourgeois critiques from modernist circles and little magazine groups, Livesay and Marriott, along with the poets Floris McLaren and Doris Ferne, started their own modernist magazine. Granting editorial authority to their friend Alan Crawley, the magazine, titled Contemporary Verse, ran from 1941 until 1952 in Vancouver, and later Victoria. Notably, the West Coast-based magazine defined itself against both the overtly political focus of the little magazines of the 1930s, and the more exclusive stance initially fostered by the Preview group. The vision put forward in “Statement,” which appeared in Preview’s first issue in March 1942, advocated for the magazine as a place for mutual discussion and criticism among members of its literary circle, and aimed to adhere to a literary approach influenced by the editors’ explicitly anti-fascist political stance:

“The poets amongst us look forward, perhaps optimistically, to a possible fusion between the lyric and didactic elements in modern verse, a combination of vivid, arresting imagery, and the capacity to ‘sting’ with social content and criticism” (McCullagh 12).

In response to the Preview piece, Alan Crawley articulated the position of Contemporary Verse in the magazine’s June 1942 issue, that it was not “the chapbook of a limited or local group of writers.” Contemporary Verse also did not reflect the comparatively militant, agitational, or parochial tendencies that historically characterized literary circles invested in avant-gardism. Instead, the goals of Contemporary Verse were to pursue an alternative path for Canadian modernist poetry:

“The aims of CONTEMPORARY VERSE are simple and direct and seem worthy and worthwhile. These aims are to entice and stimulate the writing and reading of poetry and to provide means of its publication free from restraint of politics, prejudices and placations, and to keep open its pages to poetry that is sincere in theme and treatment and technique” (McCullagh 12).

In the years following the Great Depression, Contemporary Verse therefore set out to complicate and expand the concerns of Canadian poetry by re-orienting its poetic interests beyond merely reflecting the political ideals that had characterized many modernist writer’s work throughout the 1930s. This shift of vision also appears to have gendered implications. According to Pauline Butling, the magazine fostered a supportive and open literary culture that inspired a new generation of Canadian poets, especially those identifying as women, who were encouraged to submit their work to Contemporary Verse, as well as other little magazines. Significantly, between thirty and fifty percent of the poems that appeared in every issue were by women, a result of the magazine’s progressive editorial values and expanded appeal to emerging writers (Irvine 87).

The differences between Contemporary Verse, Preview, and First Statement also highlight geographical disparities in publishing. Despite attempts to represent writers from all across Canada, the unintended bias of First Statement and Preview towards publishing eastern-based writers became increasingly clear. As neither Dorothy Livesay nor Earle Birney—both Vancouver-based poets—ever appeared in the pages of First Statement, the comparatively public-oriented perspective of the Contemporary Verse editors also helped address the relative isolation of poets based in Western Canada.

Reflecting back to F. R. Scott’s 1927 poem, “The Canadian Authors Meet,” which first articulated the struggle for emerging Canadian modernists to define themselves against the traditionalist “Maple Leaf” school, the question of what would count as “Canadian” in the creation of Canadian literature in the following decades therefore remained central to the shifts in little magazine culture throughout the 1940s. Further, Livesay’s interjection in the second clip of the 1978 recording, when she briefly challenges Marriott to elaborate on her point of view concerning the proliferation of little magazines in the 1970s, also touches on the ongoing tensions between the writer’s relationship to shifting definitions of ‘the public.’ Here Livesay posits her concern—of whether increased accessibility is necessarily “a good thing”— as a potential barrier to the modernist impulse to develop innovative and nuanced poetry capable of representing the complex issues of the times. Although the perceived divisions between the Montreal and West Coast little magazines were arguably less pronounced than the modernists and the traditionalists in the 1920s, these clips presenting three representative figures of modernist poetry—Layton from First Statement, and Marriott and Livesay from Contemporary Verse— provide an opportunity to reflect upon both their competing philosophies and mutual visions for developing a thriving, passionate, and engaged Canadian literary culture.

Works Cited

“Dorothy Livesay, P.K. Page and Anne Marriott: Poetry of the 30s and 40s.” 27 June 1978. Sound recording. F231-1-2-0-0-26, Simon Fraser University Sound Recordings Collection. Simon Fraser University Archives, Burnaby B.C. April 5 2021

Irvine, Dean. Editing Modernity: Women and Little-Magazine Cultures in Canada, 1916–1956. University of Toronto P, 2008.

McCullagh, Joan. Alan Crawley and Contemporary Verse. University of British Columbia Press, 1976.

O’Rourke, David. “First Statement (1942–5).” The Oxford Companion to Canadian Literature, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, 1997.

—. “Preview (1942–5).” The Oxford Companion to Canadian Literature, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, 1997.

Woodcock, George. “Contemporary Verse (1941–52).” The Oxford Companion to Canadian Literature, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, 1997.