Processes and Personal Reflections on Data Collection: A Conversation Among Cataloguers

November 18, 2022

Introduction

Jason Camlot (Professor in the Department of English, Research Chair in Literature and Sound Studies at Concordia University)

Since 2016, the “Where Poets Read” online listing of literary events in Montreal has posted details of nearly 800 readings.[1] The last “live” in-person event listed on the site (until recently) was for the Épiques Voices: Bilingual Poetry Show held at La Vitrola on March 10th, 2020, an omnibus bilingual show co-hosted by Katherine McLeod and Catherine Cormier-Larose. I remember this event very well, not only because of the superb readings it showcased, but especially because it was the last public poetry event I would attend in person for a very long time.[2] For 593 days, to be exact.

Figure 1. Online ticket sales for Epiques Voices event, 9 March 2020.

Between 12-29 March 2020 the “Where Poets Read” listing showed a series of notices for “cancelled” or “postponed” shows. You would find messages on Facebook like this one from Ian Ferrier, organiser of the Words and Music Show:

Tonight’s show is not cancelled, only postponed. We are collecting tracks from all the performers who were scheduled to present, and preparing the way to present them live in this group sometime this upcoming week

Stay tuned and stay safe!

Ian Ferrier[3]

The very language of this postponement message suggests a lack of vocabulary to describe the emerging situation and the nature of many virtual events to come. Ian Ferrier has organized the Words and Music show in Montreal for over twenty years without ever taking more than a month or two off. I am a longtime creative colleague of Ferrier. I also hold two more official roles in relation to the Words and Music Show. As director of the SpokenWeb research network, I am collaborating with Ferrier in developing a digital presentation of the audiovisual collection documenting his reading series dating back to the year 2000.[4] And as a board member of the Quebec Writers Federation (QWF) until very recently (my five-year term ended in May), I was the official liaison with the Words and Music Show, a vaguely-defined role that suggested I should be there to support Ferrier’s efforts (which are partly funded by the QWF) to curate literary performance in Montreal, and to report back to the board on those activities. Due to these various roles, and because I did not want the Words and Music Show to disappear, in the last week of March 2020 I found myself working with Ferrier to find a way to keep the show going, online, in response to new COVID-19 restrictions around social gathering. That joint effort to move the Words and Music show online for a first virtual show on 29 March 2020 (via my institutional [Concordia University] Zoom account) – an event we were sure was just a short-term stop-gap measure – turned into a two-year collaboration in co-hosting sixteen Words and Music shows (featuring approximately 80 performers) on Zoom, through the various and waves of the prolonged global COVID-19 pandemic as it was experienced within the specific social restrictions mandated in Quebec.

I have already pursued a first reflection on this long series of virtual, pandemic-period Words and Music shows in an extended audio essay published as part of the SpokenWeb podcast series.[5] And I have just completed a first article that reflects on the impact that the pandemic has had on the English-language literary community in Quebec, and that weaves reflections on this period from over a dozen literary organisers in the province that I collected through preliminary, email interviews. That article will be published as a chapter entitled, “Long Literary COVID: Pandemic Events in English Montreal,” in French, in the edited collection, Réagir, créer, persévérer: La culture Québécoise au temps de la pandémie (emerging from a conference of the same title), edited by Hervé Guay, Louis Patrick Leroux, and Sandria P. Bouliane, forthcoming with University of Montréal Press in 2023.

All of the situations and actions I have described up to now – my account of initial event cancellations, my involvement in helping out with the Words and Music Show online, my podcast reflections on that experience, my chapter based on interviews with artist-friends in Montreal – represent experiential responses to the pandemic as it has had an effect on the way events and communities have had to adapt to restrictions imposed by the pandemic. My way into thinking about the significance of the pandemic for literary activities and communities was through direct experience, and I remain extremely interested in collecting stories about others’ experiences concerning how the pandemic has affected literary culture and community in Canada. At the same time as I was deeply entrenched in adaptations to pandemic conditions in Quebec, I began to wonder about how the pandemic was impacting literary networks across the country, and worked to sketch out a project that might allow us to collect and present that information in interesting and useful ways. This wondering developed into a full-fledged research project that I developed as an application for a SSHRC Insight Development Grant entitled, Archive of the Digital Present for Online Literary Performance in Canada (COVID-19 Pandemic Period). As I was imagining a project that might be interestingly and usefully attendant to social disruptions and restrictions, upon literary communities in Canada as a result of the pandemic, I honed the possible directions such a project might take down to three primary objectives. The first goal would be to develop a searchable, open access database and directory – what we would call The Archive of the Digital Present (Pandemic Period) or ADP for short– that may be used by scholars, literary practitioners, and the public, for reflection, study and analysis of this period of literary activity by gaining knowledge about the nature and significance of online events that have occurred, through the collection of robust metadata, and, in some cases, with direction to audiovisual (AV documentation of the events themselves as they were held using platforms such as Zoom, Facebook Live, Crowdcast, Instagram and YouTube.) From this objective, and emerging from the process of the community and user-oriented design research and development we would pursue, came the second goal: to gather qualitative information about the significance of pandemic-period events to creators, contributors and attendees, with an oral literary history protocol that will gather stories about these events. And, of course, with all of that quantitative and qualitative data in hand, the third goal would be to analyze, theorize and publish work about the import of online literary events and gatherings during the pandemic period from aesthetic, historical, sociological and phenomenological perspectives, using approaches from the interdisciplinary field of sound studies, and with a particular focus on questions of pandemic listening, presence, community, temporality, mediation, context and space.

The present article is about a most important, complex and necessary task: that of collecting data (information) about literary events that have taken place during the pandemic. How many shows did go on despite pandemic restrictions? When did they occur? What was the nature of these events? Where did they take place (or where were they hosted, if they were virtual events)? Who organised them? Who participated in them? What kinds or “genres” of literary events were held online during the pandemic? Etc. These were some of the core data categories we started with as we began to consider collecting metadata that helps describe and organise information about as many pandemic literary events as possible. The underlying premise of this project is that literary readings and events represent a significant form of literary communication, dissemination, circulation and community-building. The data we were seeking would allow us to understand what literary activities happened in Canada between March 2020 and March 2022, with additional information about the who, when, where, how, and even, sometimes, why, they happened.

The process of collecting data about pandemic-period literary events in Canada began with an initial list of categories that I felt might be important to use for searching, comparing and knowing them. I brainstormed with English MA student Salena Wiener about these initial data collection fields, and we came up with a list that included the names of organisers and organizations, their contact information, social media and websites used, number and types of events, whether AV documentation of the event exists online, the platform used to host the event, and a few others. Salena will say more about what she then did with those categories, below. Following this initial list and data search, which revealed hundreds of events and helped us to understand the scale of the search ahead of us, Salena and I turned to the SpokenWeb metadata schema that currently structures the Swallow metadata ingest system, and we developed a crosswalk between the Swallow-system schema and key fields as we would require them for this project. We devised a paired down schema adapting some thirty-five specific data fields to fill out the overarching SpokenWeb schema headings of Institution and Collection, Item Description, Creators, Contributors, Digital File Description, Dates, Location, Contents, and Notes. With the crosswalk prepared, the data entry could begin. Salena worked on filling in the data concerning the events she had already discovered during her initial social media search. Then, with funds from the SSHRC IDG grant (the application was successful!) we were able to expand the data curation team. Salena trained two more English MA students, Aaron Obedkoff and Frances-Grace Fyfe. Aaron and Frances-Grace (F-G) organised the initial spreadsheet that Salena had created and turned it into a data processing log-sheet, which helped them keep track of their work as they progressed through creating new item entries for each pandemic literary event on the list, in Swallow. This accelerated the data collection and input into Swallow significantly.

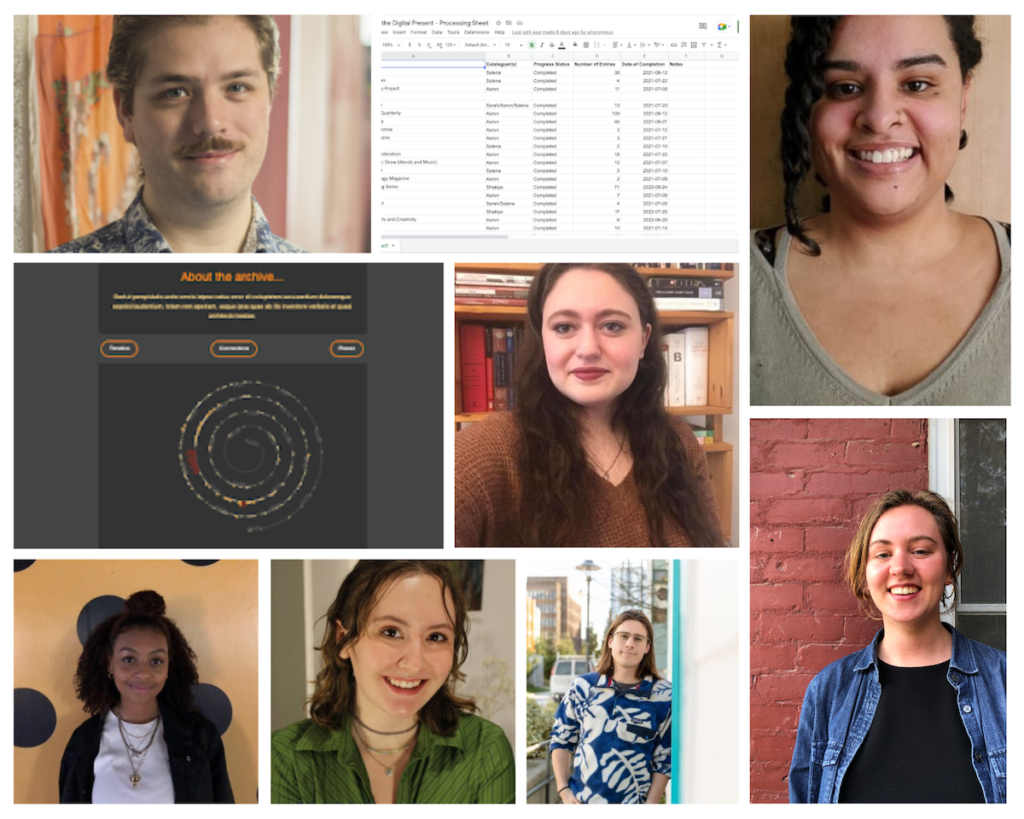

I should note, as an important aside, that as the ADP dataset grew in size, intensive work was underway in user-design testing, full-stack development, and approaches to data visualisation for the website that will eventually present all of the data we are still in the process of collecting about pandemic-period literary events. Details about the design and development projects will appear in future SWB articles.

Figure 2. Draft of Graphic User Interface for Archive of the Digital Present

Data processing was moving at a good pace, but we decided that there must be more data out there that we hadn’t yet captured from the initial list Salena had created from her scan of social media posts. This sense that there were more events and organisations than we had learned about so far was corroborated by the regular discovery of new events and sources of event information as Aaron and F-G pursued research around the known events they were cataloguing. New events and organisations kept popping up along the way. So, we decided to expand our cataloguing team further. This would allow us to work intensively on cataloguing known events, but also to devote some time to seeking additional data for the project. We put out a job posting seeking two (or maybe three, we thought) additional undergraduate Research Assistants (RAs) to assist in this work. We had a very large number of excellent applications for these positions and due to the excellence of the applicants we interviewed, we ended up hiring four additional students to join the cataloguing team, namely: Diya Dekhar-Powell, Theodore Fox, Olivia Hornacek, and Shakiya Williams. With this full cataloguing team on board during the winter term moving into the spring and summer, we worked on developing a strategy for discovering additional events that occurred during the pandemic, fine tuning our metadata fields, attending to some unexpected questions that arose from the cataloguing work, as well as other interesting discoveries and points of reflection that has made this part of the project a veritable adventure in data collection. As we know well from our significant experience in data curation and structuring for the SpokenWeb research program, metadata – which is most succinctly defined as “data that provides information about other data” is often the source, in practice, of some of the most important research questions we can imagine, about scope and definitions, ontological concepts and categories, and about the methods we use to describe, grasp, and analyse the very entities, literary events and activities, that are at the core of this mode of literary historical research. The following contributions from the cataloguing team that is making the Archive of the Digital Present a source rich in data about what Canada’s literary communities made happen during the COVID-10 pandemic, present a glimpse of the lessons learned from this extensive exercise in defining, seeking, finding, and structuring data about pandemic literary events.

[1]. Katherine McLeod, “Where Poets Read,” accessed February 1, 2022. http://wherepoetsread.ca/

[2]The “Épiques Voices bilingual poetry show” was staged as part of the Festival Dans ta Tête on March 9, 2020, 8pm, at La Vitrola, 4602 St-Laurent, Montréal, QC, Canada. https://lepointdevente.com/billets/czz200309002

[3] Ian Ferrier, “Tonight’s show is not cancelled,” Facebook, March 22, 2020. https://www.facebook.com/wordsandmusicshow

[4] For information about SpokenWeb see: https://spokenweb.ca/

[5] Jason Camlot, “The Show Goes On: Words and Music in a Pandemic,” SpokenWeb Podcast, Season 3, Episode 5, accessed February 20, 2022. https://spokenweb.ca/podcast/episodes/the-show-goes-on-words-and-music-in-a-pandemic/

Salena Wiener (MA student in English literature, Research Assistant and Data Collection Project Lead)

|

I began my Masters of English Literature at Concordia in September 2020, during the early months of the pandemic hitting Montreal. I had spent the summer scrolling through my social media timelines, watching my local literary organizations advertise online events, and even attending a few myself. When I was hired to conduct the initial research of compiling a list of literary organizations across Canada who were hosting events online since March 2020 for SpokenWeb’s new project “Archive of the Digital Present”, my first strategy was to return to those social media pages of local organizations which I followed and begin adding them to the list. At first, I thought Twitter would be the most efficient way to find events, as this was the first place that I had started to read about events moving online. But I quickly found that the platform was difficult to navigate as one would have to scroll down an organization’s Twitter feed (at this point, it was December 2020, so this would mean sifting through months of Tweets to identify events which took place online in March 2020 onward). |

I quickly moved to Facebook, and found this to be a much more efficient platform for data collection, as Facebook has a built-in function to archive past events on an organization’s page. By clicking onto an organization’s Facebook page, and moving to their “Events” section, I was able to quickly scroll through their past events and see whether they’d hosted events online since March 2020, and if they had, how many. If they had, I recorded the name of the organization, the number of events hosted online since March 2020, a link to their Facebook page, Twitter, website, and other details in an excel spreadsheet. I also “Liked” the Facebook page of the organization, which allowed for Facebook to connect me with other organizations that were ‘similar’ or connected to the organization through their ‘suggestions’ function. Using their algorithm which connects me as a Facebook user to other pages I might like as a research tool, I was able to quickly find new organizations to click through and record in my list, but this method also made me hyper-aware of my own bias. My Facebook suggestions were originating from my local list of organizations which I had been personally connected to or aware of. I also took the approach of asking people I knew (either through direct message, or through a post) if they were aware of organizations holding events online, and while this perhaps offered a more diverse range of data to work with, it was still subjective and limited to my own network.

Wanting to expand my search of course beyond Montreal and to the wider Canadian literary landscape, and also wanting to achieve a greater level of objectivity in my search, I switched my starting point from Facebook to Google. I began to google lists of various categories of Canadian organizations (for example, Literary Festivals or Literary Magazines or Presses, etc..). Once I found a list of organizations in a given category, I went through each organization on the list, checking their Facebook Events page to see if they had hosted events online, and then recording their data if they had. Each time I found a new organization, I would “Like” the page, which would often connect me with other organizations in that region. This approach allowed me to reach a broader range of events geographically, and Facebook’s ‘suggestion’ algorithm conveniently carved out networks of literary communities that were interconnected through their social medias, and that I hadn’t previously been aware of. As I researched and went through list after list, and continued to record organizations in the fashion described, I thought about questions of representation as well; I scrutinized whether these lists which I was finding adequately included diverse perspectives, i.e, if these organizations on the list included organizations which hosted events by marginalized communities or focused on marginalized literatures of various groups. If I found that they hadn’t, I tried to google key words to find organizations by and for underrepresented communities, and to record their data.

This approach, while perhaps more objective, was still being conducted by myself, one researcher (under the supervision and insight of the P.I as well, of course). The project then expanded to more research assistants to begin cataloguing work. Aaron Obedkoff was hired onto the project in the Summer of 2021, and Frances-Grace Fyfe joined shortly after in the Fall.

Aaron Obedkoff (MA English, Research Assistant, Cataloguer)

|

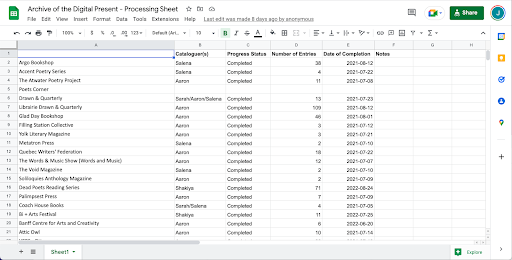

I started on the project shortly after Salena completed the first draft of the “processing sheet” – the Excel document which lists all of the organizations that we have, or will, complete data entries for.

Figure 3. Screenshot of the ADP team’s processing excel sheet.

|

As such my work primarily involved completing entries for the organizations that had already been noted. During this process, however, I began to notice that many events were co-hosted with organizations that we had not yet included on the processing sheet. This often took the form of a festival or larger publishing house collaborating with a smaller, more local organization. For example, the Toronto International Festival of Authors hosted events in association with the Toronto Poetry Slam. These network visualizations were both a helpful way to track collaborations between organizations and expand our processing sheet.

Frances-Grace Fyfe (MA English, Research Assistant, Cataloguer)

……………………………….……………………….. |

Although at this point the other team members had largely concretized the cataloguing process, I felt (alongside them!) that some interesting cataloguing ambiguities remained.The three of us had several conversations, for example, about how to tag creators whose roles were not always clearly defined from the source material: is an “interviewer” also, necessarily, a “speaker,” or should that tag be reserved only for the interviewee? Similarly, is an “interview” always, by necessity, a “conversation”? (We decided to tag an event as an interview only if it was explicitly advertised as such; otherwise, we would consider an informal talk between an author and host(s) a conversation among “speakers”). These conversations allowed us to think more specifically about the archive’s “ontologies”–how the way an event gets catalogued shapes how researchers will later consider what it was. |

In conversations with the team lead, we also spoke about what counted as a “literary” event, given that a festival might, for example, host an event about a topic that was not expressly “literary” (say, a book launch on a work of political theory). We decided that, in cases where the “literariness” of the object of study was ambiguous, we should try to determine if the book being presented fit into genre conventions as laid out in the Swallow metadata fields (poetry, fiction, or non-fiction such as memoir). Likewise, we noted that some events, although not expressly advertised as such, may include literary “components” which should be noted: one Annual General Meeting for a reading series group included a spoken word performance by the youth poet laureate, for example.

Like Aaron, I also continued to add to the processing sheet as I came across events that were co-hosted by collections hosts not otherwise catalogued.

After this phase of primarily cataloguing work, we wanted to more intentionally do a second phase of data collection to do our due diligence and fill out organizations that might have been missed in Salena’s initial list, before turning to social media to ask organizations to contact us to be added. We also wanted to increase the rate at which we could catalogue the data for the organizations already one our list. We hired and trained four new research assistants onto our team: Diya Dekhar-Powell, Theodore Fox, Olivia Hornacek, and Shakiya Williams. We decided in a team discussion that we would proceed by assigning categories for each person to research and add to the list. We began with the following: English departments in Canadian Universities + Humanities Departments in Colleges (FG), Literary Journals and Magazines (Aaron), Literary Festivals (Shakiya), Literary Associations and Federations (Diya), Libraries: Public, Municipal, Town, etc (Theodore), and Literary Presses (Olivia). By this point, we had also made the decision to include not only online literary events, but events which took place in-person, or were cancelled, postponed, or rescheduled, since March 2020 into our data set.

Theodore Fox (Undergraduate in English, RA Cataloguer)

|

………………………………………………… |

When I tried to see how many public libraries there were in Canada, I found a 2019 summary for the University of Ottawa which complains about the unavailability of the figure and attempts to find one. It puts the total number of library systems at 652 and the total number of branches at 3,350. Quickly, it became obvious to me that cataloguing every event at every public library would be outside of our resource scope. I came up with a rough methodology to choose example library systems so as to try to cover libraries serving a variety of communities across Canada. Included would be those library networks serving the three largest municipalities in each province or territory, as well as those serving each provincial or territorial capital, as those seemed to have disproportionately high numbers of literary events, regardless of the population served. For those provinces or territories which did not include a rural library network within those already added at this point, I added an additional rural library chain. |

Different types of literary events appear to be more common in different parts of the country, with, for instance, oral history events being particularly common in BC, while presentations of self-published history books were common in the Maritimes, and much less common elsewhere in the country. Small town libraries made me question what kinds of events we needed to include in our collection. A periodic open mic for poetry might not be an event worthy of catalogue in an urban context, but for rural communities, it might be a central and significant literary event for the population of the area. A children’s author visiting a regular storytime for children event might be the highest profile author to visit a small community, despite the audience for that event being outside of who we commonly think of as the literary audience.

Shakiya Williams (undergraduate in English, RA Cataloguer)

……………………………………………. ……………………………………………. |

When beginning my research for literary festivals, the first place I thought to look was through my aunt’s Facebook event page. She has always been my source for upcoming literary events – and the person who took me to my first literary festival a few years ago. Therefore, I knew she would have attended some virtual events in 2020. She is also a teacher and likes to attend events that advocate for diversity, which was a main focus of mine when researching. On my aunt’s Facebook, there were a few literary events by individual authors but not many festivals. This caused me to also search through the author’s Facebook events page to see if they had attended or were a part of any literary festivals. After finding as much as I could from her Facebook page, I decided to resort to Google. Many of the lists I found showed festivals that had taken place during the pandemic in 2020 but not for any time period after that. This then brought up the idea of festivals that did not get the chance to reschedule their events for 2020 but were able to for 2021. So, I looked for events that took place in 2019 and went on their social media accounts to see if they had planned to come back for 2021 or 2022. This step was helpful, as it resulted in finding festivals that did not take place within the first year of the pandemic. |

Olivia Hornacek (Undergraduate in English, RA Cataloguer)

|

|

When researching literary presses to add to the organisations to be catalogued list, I initially combed through the Literary Press Group of Canada (LPG) website in the members section. Some of the links connecting to the Press’ website were outdated so I looked them up externally individually and checked their social media pages to ensure they had events during the Archive of the Digital Present’s time slot. After combing through the Literary Press Group of Canada, I then moved onto searching through Canadian writing blogs that had recommendations for aspiring authors to submit to, some of which were smaller presses but there were a few big ones that didn’t belong to the LPG. Again, many of these links were outdated so I had to look them up externally and check their social media for events. As I began to look through these events I noticed that many of the presses that had events prior to March 202 usually took place in a specific bookstore the press had developed a connection to. After March 2020 however, some of the presses that had few or no events before the pandemic began to host virtual events. It’s interesting to see the new opportunities the pandemic’s shift to the digital realm offered smaller organisations. |

Diya Dekhar-Powell (Undergraduate in English, RA Cataloguer)

|

|

My research began by initially looking at the broader list of the literary associations and federations all around Canada. Fortunately, I found a large amount of organisations through various Canadian authors websites online. These sites were incredibly helpful as they each provided an accompanying link with the association name, saving me the time to look up each individual name. From here, I was able to compile a list of these associations. At this stage of my research I had discovered an obstacle in collecting data. I had found that there were various literary associations and federations that had little to no current information on their websites. In this case, there was a limitation to the accessibility to such data that could not be found online. With no digital footprint such events become difficult to capture or record, which nonetheless highlights the impact of online documentation for the use of archives. It shows that we are now in an age where our online activity has become far more substantial in documenting our attendance, participation and collaboration to such literary events. From this point on however, I further investigated these organisations by browsing their social media presence, which became more promising, especially on Facebook. Even so, I think this research has shown me how far we have come with technology and its supplementary use of evidencing our experiences. |

Frances-Grace Fyfe

I’m working on inserting the links to the respective departments’ online channels for advertising events into the Data Collections Processing sheet. After a quick Google search on “Canadian University English Departments” did not yield any results, I went through the list of “Campus Representatives” on the Association of Canadian College and University Teachers of English website, which lists each campus rep to their university or college. Unlike most literary presses or booksellers, who typically at least advertise events on Facebook, university English Departments seem to advertise their events in a number of diverse places: on department websites hosted by the university, on personal websites created by departments themselves, on Facebook, or on Twitter. The list of events will not account, for example, for events that were advertised only through a department’s private email listserv. Important to note is that some English departments co-host literary events with film and theatre departments, with whom they may or may not share an advertising channel. Archiving university English department events brought up the question of whether or not we should include academic conferences–we ultimately decided against it since the network had not typically archived academic conferences which were in-person, but it did raise questions about how certain events may have become more accessible as they moved online.

Aaron Obedkoff

Given our familiarity with the Canadian literary scene as students of Literature – more than once I catalogued events that featured friends and classmates – many of the relevant literary journals and magazines had already been documented on the processing sheet by the time I joined the project. When it came time to conduct another round of research to expand the processing sheet, I focused on smaller and more regional publications. A helpful resource in this process was an article published by the CBC several years ago compiling a list of magazines accepting submissions from writers, as well as a similar list from the National Magazine Awards. Some of the publications had become defunct in the meantime, but many were still actively hosting events throughout the pandemic. With limited operating budgets and sometimes volunteer staff, it was common for these publications to host just a small number of events. Commonly, these events would celebrate the launch of a new edition of their respective journals.

Salena Wiener

When I began my degree amidst the beginnings of the pandemic I was overwhelmed with the sense that studying literature in a moment of global unrest might not be the most meaningful or productive thing I could be doing. The classic question, “Why study Literature?” or “Why do the Humanities matter? – questions to which I had always thought I had an answer, suddenly seemed to burn with new urgency and offer more confusion than clarity. I moved through my first semester of graduate school more or less just going through the motions. But when I began working on the Archive of the Digital Present project, and continuing that work through my degree, I found a structured and meaningful way to engage with the pandemic around me. Making lists and processing data took what was vague and intangible – the threat of viral infection – and rendered it small, systematic, and concrete. Something to be analyzed. Something to be entered into a meta-data ingest system and turned into potential answers to a set of research questions. The discussions and debates about how to catalogue this data with the team animated my time here throughout my degree. Watching the team continue to catalogue over 2000 entries to date, and more to come, has brought some small comfort in a time of crisis. And as we move towards a conclusion to the pandemic and to cataloguing the vast amount of meta-data for the database, I’m confident these entries will offer new ways to make meaning out of this Pandemic Period in literary studies for graduate students, scholars, creative practitioners, librarians, Canadians, and peoples alike.

To experience the data collected and curated by Salena, Aaron, Frances-Grace, Theodore, Shakiya, Diya, and Olivia, please visit the Archive of the Digital Present website. New data will continue to be added until the end of 2022, and new ways of searching and faceting the data are being added through the ongoing ADP web development project. If you organized or participated in a literary event between March 2020 and March 2022 that does not appear in our data set, please reach out to us so we can add that information to our database, at spokenweblog@gmail.com