| (00:00) |

SpokenWeb Podcast Theme Music |

[Instrumental overlapped with feminine voice] Can you hear me? I don’t know how much projection to do here. |

| (00:18) |

Hannah McGregor |

What does literature sound like? What stories will we hear if we listen to the archive? Welcome to the SpokenWeb Podcast, stories about how literature sounds. [SpokenWeb theme music fades] |

| (00:34) |

Hannah McGregor |

My name is Hannah McGregor, and – |

| (00:36) |

Katherine McLeod |

My name is Katherine McLeod. Each month, we’ll bring you different stories that explore the intersections of sound, poetry, literature, and history created by scholars, poets, students, and artists across Canada. |

| (00:50) |

Katherine McLeod |

Caedmon Records. Did you know that Caedmon Records was the first label to sell recordings of poetry? Well, you might have known that, but did you know that it was started by two women? I didn’t know that before listening to this episode.

|

|

|

In this episode, producers Michelle Levy and Maya Schwartz revisit the early history of Caedmon by listening to an interview with its founders, Barbara Holdridge and Marianne Mantell, an interview that was conducted by Eleanor Wachtel for CBC Radio.

|

|

|

In listening to this episode, I was struck by how we are hearing the history of this formative record label for recording spoken word, hearing it as a story being told out loud on the radio. |

| (00:01:35) |

Katherine McLeod |

Michelle and Maya then pay tribute to Holdridge and Mantell’s legacy by listening to two poems from the Caedmon Treasury of Modern Poets Reading, first released in 1957. They listen to two experts and talk about what they heard.

|

|

|

Michelle discusses Robert Frost’s recording of “After Apple-Picking” with Professor Susan Wolfson of Princeton University, and Maya chats with Professor Stephen Collis of SFU‘s English department about William Carlos Williams’s reading of the “Seafarer.”

|

|

|

All of the archival audio in this episode is held in SFU‘s archives and special collections. But this Caedman record that these poems were recorded on, Caedman Treasury of Modern Poets Reading, was a popular one. And as I listened, I went over to my bookshelf and pulled it out. Yes, I happened to have a copy of this very same record. I take it out of its cover, I put it on, lowering the needle – |

| (00:02:35) |

Audio |

[Static audio starts playing] |

| (00:02:42) |

Unknown |

If I told him, would he like it? Would he like it if I told him? Would he – |

| (00:02:46) |

Katherine McLeod |

Here is episode four of season five of the SpokenWeb Podcast. “Two Girls recording literature: Re-listening to Caedmon Recordings.” |

| (00:02:56) |

SpokenWeb Podcast Theme Music |

[Instrumental Overlapped With Feminine Voice] |

| (00:03:06) |

Michelle Levy |

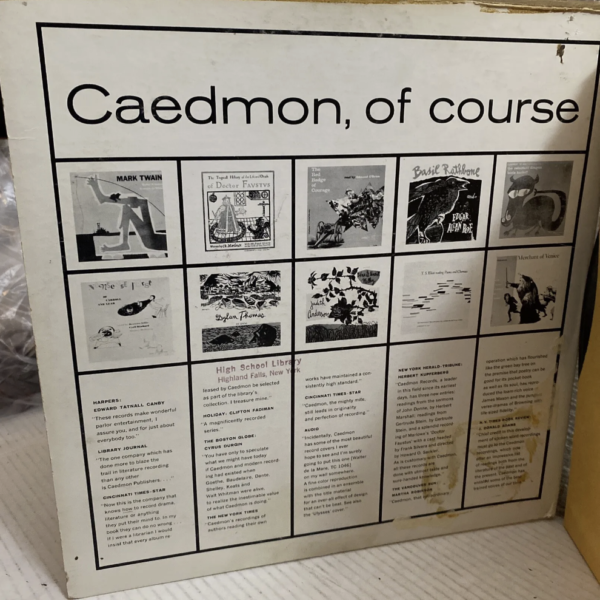

If you have ever rummaged through a box of cassettes in a library, or secondhand bookshop, or flipped through LPs in a thrift store, you will probably stumble across a Caedmon recording. These feature poets, playwrights, and fiction writers reading from the work originally released on vinyl and later on cassette.

|

|

|

Caedmon is a record label founded by two women, Barbara Cohen Holdridge and Marianne Roney Mantell, in 1952. Recent graduates of Hunter College, Holdridge was working in book publishing, Mantell in the music recording industry when they heard that Dylan Thomas was reading at the 92nd Street Y in New York City. They attended this reading and finally prevailed upon him to record with them. And the rest, as they say, is history. The creation of the first business to capture audio literature for a mass audience.

|

|

|

[Soft piano begins to play in the background] In this episode, we want to bring to the surface the critical role that Holdridge and Mantell played in this early history of spoken word recordings. |

| (00:04:14) |

Maya Schwartz |

This episode begins with a brief overview of Holdridge and Mantell’s founding of Caedmon. The women told their story in a marvellous interview with Eleanor Wachtel. Given now over 20 years ago, in 2002, to celebrate Caedmon’s 50th anniversary and recently rereleased to celebrate Wachtel’s incredible 33-year run as host of the CBC’s Writers and Company.

|

|

|

We draw from this interview to allow us to hear Holdridge and Mantell telling their story in their own voices. |

| (00:04:46) |

Michelle Levy |

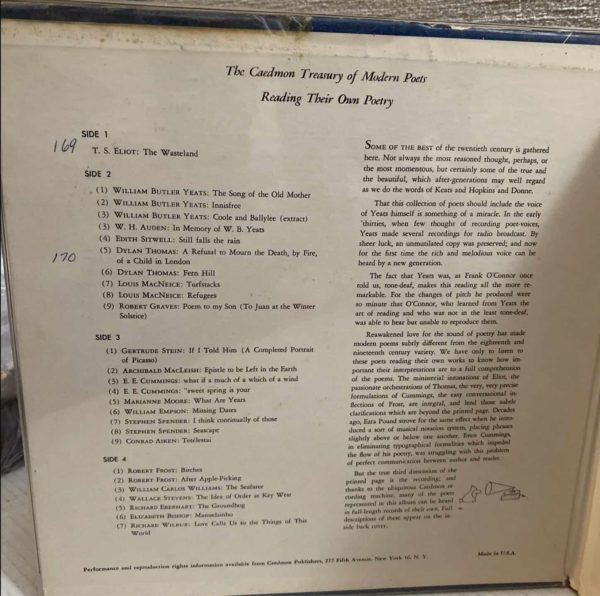

In the second and longest part of this episode, we pay tribute to Holdridge and Mantell by re-listening to two poems from one of their recordings, held in SFU’s special collections, The Caedmon Treasury of Modern Poets Reading, an anthology first released in 1957.

|

|

|

Maya and I each selected a few poems from this collection that we enjoyed listening to and asked two colleagues, both of whom were scholars of poetry, as well as poets themselves, to share their thoughts on the recordings. I discussed Robert Frost’s reading of “After Apple-Picking” with Professor Susan Wolfson of Princeton University. Maya chatted with Steve Collis of our English department at SFU about William Carlos Williams’ reading of the “Seafarer.”

|

|

|

We talked about what it meant to listen as opposed to reading these poems on the page. What elements of the poet’s performance surprised us, as well as a range of other details, from the pronunciation of certain words to the speed at which they read? We notice, for example, how Frost ignores line breaks in his reading, whereas Williams gives great emphasis to them. These elements of the poem’s delivery provide what Barbara Holdridge described to Wachtel as third-dimensional depth. |

| (00:06:04) |

Barbara Holdridge, Writers & Company Interview, 2002 |

The idea was that we were not supplanting the printed book; we were augmenting it and giving it a depth, a third-dimensional depth that a two-dimensional book lacked. |

| (00:06:19) |

Michelle Levy |

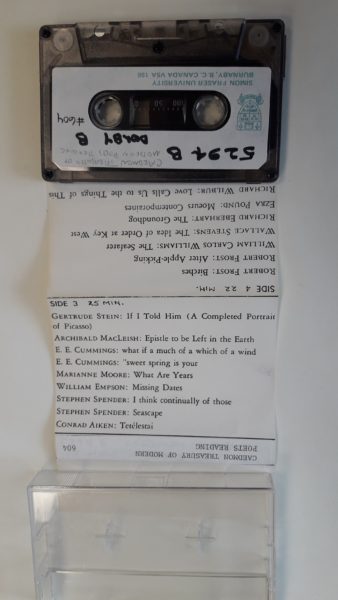

If you look at a Caedmon recording, you’ll find little contextual information. In the treasury held at SFU, we no longer have the original LP or cassette. It apparently has been discarded and re-copied onto a new cassette. Further, we have only half of the treasury, the third and fourth sides of the LP, as it was first released. The first and second sides, which included Dylan Thomas’ “Christmas in Wales,” do not make it into our collection.

|

|

|

In the Writers & Company interview with Holdridge and Mantell, however, we learn crucial details about their motivations for recording poets. |

| (00:06:55) |

Marianne Mantell, Writers & Company Interview, 2002 |

I came to this concept as a result of attending too many classes in literary criticism. I had a strong sense that what I was hearing and what I was reading had to do with the critic and not with the poet or the author. And here was an opportunity to create, or to find another original firsthand source: what the poet or author heard in his or her mind. |

| (00:07:26) |

Michelle Levy |

Here, Mantell explains how they’ve worked with authors prior to recording. |

| (00:07:32) |

Marianne Mantell, Writers & Company Interview, 2002 |

I think also we didn’t just take them and sit them in front of a microphone. We spent a lot of time beforehand with the author in an effort to shake off that sense of tightness, uptightness, and fear that one gets in front of a microphone, particularly an author who says, “Oh, I’m not a performer. I’m…” It’s okay, we’re here. Just talk to us. |

| (00:08:01) |

Maya Schwartz |

In addition to meeting and recording authors, Holdridge and Mantell were also running a business. Here’s what they had to say about that experience. |

| (00:08:11) |

Barbara Holdridge, Writers & Company Interview, 2002 |

It was wonderful. Men were not hostile. They were very accepting. We found a young banker, a vice president, who eventually lent us money. We used to trundle our little cart named “MattiWilda” from our offices on 31st Street to the RCA plant on 24th Street and bring it back, loaded with heavy boxes of records, long-playing records, and along the way, dozens of men would spring to our sides to help us up the curb and down – |

| (00:08:47) |

Marianne Mantell, Writers & Company Interview, 2002 |

[Overlapping] We couldn’t have done it by ourselves. |

| (00:08:49) |

Interviewer, Eleanor Wachtel |

You named your cart? |

| (00:08:49) |

Barbara Holdridge, Writers & Company Interview, 2002 |

Mattiwilda. |

| (00:08:51) |

Marianne Mantell, Writers & Company Interview, 2002 |

Well, why not? Why not? |

| (00:08:52) |

Interviewer, Eleanor Wachtel |

[Laughs] |

| (00:08:53) |

Marianne Mantell, Writers & Company Interview, 2002 |

She was named after Mattiwilda Dobbs, who was a reigning soprano of the time. |

| (00:08:58) |

Interviewer, Eleanor Wachtel |

I see. |

| (00:08:59) |

Marianne Mantell, Writers & Company Interview, 2002 |

[Inaudible: I would go that woman, but one better.] I think we probably succeeded where men would’ve failed because we were women. On the one hand, men were chivalrous. On the other hand, when they attempted to put us down because we were two girls, etcetera, etcetera, we outwitted them, we outsmarted them, and, occasionally, we drank them onto the table. [Interviewer laughs] So I think, in a major way, we were successful precisely because we were women. |

| (00:09:32) |

Michelle Levy |

In their recordings. Mantell and Holdridge create a rich archive that survives for our exploration today. Maya and I listened to the recordings. I found a few poems that intrigued me, including Frost’s “After Apple-Picking,” a poem that seems so deceptively prosaic, like a lot of Frost’s poetry. I settled on it, however, after finding that Susan Wolfson, a fellow Romanticist, had recently written an article on Frost, including a discussion of this poem and agreed to discuss it with me. |

| (00:10:03) |

Susan Wolfson |

Yeah. I’m Susan Wolfson. I teach at Princeton University in the Department of English. |

| (00:10:10) |

Michelle Levy |

Thank you for coming. A question for you just before we get to this specific recording: Do you recall if you had heard Frost reciting his poems before in other recordings? |

| (00:10:23) |

Susan Wolfson |

No. I mean, Frost gave readings his entire life. I remember his reading at Kennedy’s inauguration with great difficulty ’cause the sun was in his face, |

| (00:10:37) |

Robert Frost, at the presidential inauguration of John F. Kennedy, 1961 |

[Overlapping, Robert Frost at the presidential inauguration of John F. Kennedy]

|

|

|

The no order of the [inaudible] – |

| (00:10:38) |

Susan Wolfson |

So he couldn’t read the poem that he wrote for the occasion but just sort of pulled- |

| (00:10:42) |

Robert Frost, at the presidential inauguration of John F. Kennedy, 1961 |

[Overlapping] I can’t stand the sun. |

| (00:10:45) |

Susan Wolfson |

The problem gift outright. |

| (00:10:45) |

Robert Frost, at the presidential inauguration of John F. Kennedy, 1961 |

[Overlapping] New Order of the ages that got – |

| (00:10:49) |

Susan Wolfson |

But I was in high school when that happened. |

| (00:10:53) |

Michelle Levy |

We begin with listening to Frost reading “After Apple-Picking.” |

| (00:10:58) |

Robert Frost, reading “After Apple-Picking” |

My long two-pointed ladder’s sticking through a tree / Toward heaven still, / And there’s a barrel that I didn’t fill / Besides it, and there may be two or three / Apples I didn’t pick upon some bough. / But I am done with apple-picking now. / Essence of winter sleep is on the night, / The scent of apples: I am drowsing off. / I cannot rub the strangeness from my sight / I got from looking through a pane of glass / I skimmed this morning from the drinking trough / And held against the world of hoary grass. / It melted, and I let it fall and break. / But I was well / Upon my way to sleep before it fell, / And I could tell / What form my dreaming was about to take. / Magnified apples appear and disappear, / Stem end and blossom end, / And every fleck of russet showing clear. / My instep arch not only keeps the ache, / It keeps the pressure of a ladder round. |

| (00:12:01) |

Robert Frost, reading “After Apple-Picking” |

I feel the ladder sway as the boughs bend. / And I keep hearing from the cellar bin / The rumbling sound / Of load on load of apples coming in. / For I have had too much / Of apple-picking: I am overtired / Of the great harvest I myself desired. / There were ten thousand thousand fruit to touch, / Cherish in hand, lift down, and not let fall. / For all / That struck the earth, / No matter if not bruised or spiked with stubble, / Went surely to the cider-apple heap / As of no worth. / One can see what will trouble / This sleep of mine, whatever sleep it is. / Where he not gone, / The woodchuck could say whether it’s like his / Long sleep, as I describe its coming on, / Or just some human sleep. |

| (00:12:51) |

Michelle Levy |

So there we go. What comes to mind listening to that for you? |

| (00:12:56) |

Susan Wolfson |

You know, one surprise to me was his reading against every edition of the poem that I found to say, “cherish in hand, let down, and not let fall.” I’m wondering if in reading it, whether he, I don’t know, whether he was, he had this in memory, but in memory, he may have just decided to revise that line, or he may have misremembered it on the cue of the repetition.

|

|

|

As I said, I was a little struck by the monotone and the rapidity with which he read. And for a formalist such as Frost, who famously said things like “poetry without rhyme is like playing tennis without a net” or that “you have to have a metrical pattern for the rhythm to ruffle against.” I mean, he’s not a formalist, but he’s certainly very form conscious and form attentive. |

| (00:13:54) |

Susan Wolfson |

I was struck by how often he didn’t pause at the end of lines. In some cases, the enjambment was quite dramatic, “a load of apples coming in. / For I have had too much,” I mean makes that almost continuous, goes past the period. But this is a poem that is remarkable for varying its line lengths between 12 syllables and two syllables, with all being the shortest, one and the longest, one being the first. And that kind of wavering and the way that interplays with the surreal temporalities where you think you’re in a past tense, then you’re in a kind of present tense of remembering a past moment, and then you’re in a kind of dreamscape where those temporalities overlay, it would seem that poetic form is very much involved in those evocations too. |

| (00:15:00) |

Susan Wolfson |

But Frost reads this at such a pace that it almost sounds like prose. I know that he is committed to the kind of vernacular of poetry rather than poetic diction, which is fine. I mean, it makes his poetry sound authentic, genuine, and accessible. But I didn’t expect it to sound like prose. So that was my take.

|

|

|

But that sense that words still have a kind of constitutive magic [Music starts playing in the background] they create and produce an experience; they don’t just refer to it or represent it. And the presence of Frost is just a kind of magical enactment of that. |

| (00:15:49) |

Michelle Levy |

We then discussed how Frost recorded his poem in a studio, and we wondered whether the lack of an audience contributed to the monotone, with the result, when listening, that you lose the line breaks as well as the rhymes. |

| (00:16:02) |

Susan Wolfson |

Yeah, those are lost. And the rhymes that really are the kind of line-end punctuation, whether this is not like the verse, it is metrically various.

|

|

|

And, that’s part of its astonishment, that the way in which these lines seem organic with thinking and yet, use, avail themselves of the resources of poetic form to give a kind of pulse and poetic charge to the language. That is part of its sensuous appeal. |

| (00:16:45) |

Michelle Levy |

We then address the deceptive simplicity and accessibility of Frost’s poems, how they contain elements of recognition but also surprising depth. |

| (00:16:55) |

Susan Wolfson |

It’s a kind of ruffling of the surface that you can take these poems on. That’s why they’re so teachable: there’s immediate access to it. And then, you kind of show the students that the ground they think they’re standing on is less stable than they’d like. The joke about the road not taken is that it’s identical to the road taken. So this epic portentousness has made all the difference. It is sort of Frost’s own joke about wanting to have those allegorical moments landmarked, signposted, in your life. He’s got a great comment that what’s in front of you brings up something in your mind that you almost didn’t know you knew. Putting this and that together, that click, that’s the poetry. And sort of almost against these sort of portentous alls that almost is just a really interesting Frost mode. That it teases, it tiptoes, it borders on, but it doesn’t insist. |

| (00:18:04) |

Music |

[Instrumental music begins to play.] |

| (00:18:10) |

Michelle Levy |

And there’s that line that you quoted in your essay from Frost as a teacher who said that “the role of poetry is never to tell them something they don’t know, but something they know and hadn’t thought of saying. It must be something they recognize.” And I love that idea; it’s very Emersonian, too, but what do you think about this poem that we recognize, and is there something in particular that we recognize when listening that we don’t necessarily when reading, although that’s another layer we don’t have to get to, but in terms of this poem, what do you think some of those deeper truths are that the reader or the listener might recognize? |

| (00:18:53) |

Susan Wolfson |

The meditation is part of the every day. It’s not just something that poets do, and poets do in extraordinary moments, but that there there is a way in which this poem, which is really just about something as quotidian as apple-picking, is already possessed with a kind of mental landscape, or mental landscaping of it that takes possession, that you can find yourself thinking about just quotidian events that stay with you. That wonderful sort of memory as he’s drowsing off, before he is imagining the source of sorcerers apprentice explosion of apple after apple that I am drowsing off. I mean, there’s another present tense, right, that he is – “I didn’t fill” and then suddenly, “but I am done with apple picking now.” |

| (00:20:00) |

Susan Wolfson |

“Now” is so weird because it just means that he’s not done. It’s just this moment. So does that “now” mean existentially, now I am never gonna pick another apple again, I’ve had it with apples? Or is it just for the day? And as he’s thinking about that, and the scent of apples, which is so immediate, “I am drowsing off.” So you think, okay, well, that’s a departure from apple picking. “I cannot rub the strangeness from my sight / I got from looking through a pane of glass / I skimmed this morning from the drinking trough / And held against the world of hoary grass. / It melted, and I let it fall and break. / But I was well / Upon my way to sleep before it fell, / And I could tell / What form my dreaming was about to take.” Has nothing to do with apple picking. |

| (00:20:58) |

Susan Wolfson |

He is on his way to the orchard, and it’s a moment of whimsy and optical illusion that he indulges in, a different way of looking at the world just for a moment. And that’s what he’s dreaming of. And as he’s sort of recollecting that, it dissolves back into his dream, “what form my dreaming was about to take.” And then the form that his dream is about to take is apple-picking with a vengeance. I mean, this is partly a Wordsworthian spot of time that is captured in poetry and reproduced in the composition of the poetry itself. It comes back as an event of apple-picking in the poetry. Keats is interesting because it’s hard not to think about autumn without thinking of Keats, but Keats is not a labourer; he’s an observer. |

| (00:21:53) |

Susan Wolfson |

So when he’s looking at the boughs that load and bless, you know, they’re loaded, blessed with fruit. I mean, he’s real; his work is poetic labour, but he’s not on a ladder. Doing apple picking. Frost has a different relationship with that. This is much more Wordsworthian say in which the kind of physical events of stealing eggs from a nest high on the crags where the wind is blowing you sideways or feeling the oars tremble in your hands as your joyride in a boosted boat suddenly possesses you with a certain kind of tremor, of guilt or possible punishment if you’re busted. That’s a kind of visceral memory that Wordsworth has that he turns to poetry to reproduce because it’s so thrilling in just that, even to remember it, that he feels it all over again as he’s writing about it. |

| (00:22:53) |

Susan Wolfson |

And this is a kind of immersive, at the moment, but the moment is everywhere in Frost. It is both the day’s labour, but then after apple-picking and trying to go to sleep and not yet being asleep, but the day replaying and in surreal dimensions, in that kind of half space of mind between sleeping and waking, which, of course,, is a space of poetry. That’s what the poetic composition fills up and overfills. Even that funny little thing about the woodchuck at the end, “one can see what will trouble the sleep of mine.” That “what will trouble” whatever sleep it is, which is to say that maybe it’s not sleep at all, but it’s gonna be this sort of possession of one’s mind by the day’s labour. “One can see what will trouble / This sleep of mine, whatever sleep it is. / Were he not gone,” |

| (00:23:49) |

Susan Wolfson |

“The woodchuck could say whether it’s like his / Long sleep, as I describe it’s coming on, / Or just some human sleep.” Of all the animals to pick, I mean, woodchuck, a creature defined by its labour, right? I mean, that’s the eponym. How much wood could a woodchuck chuck? I mean, that’s, you know, he knows that he knows that riddle. And yet, even the woodchuck gets to hibernate. I mean, really, to get as close to death as you can. And just as a way of getting through the winter. Whether it’s like his “long sleep,” and that plays against “my long two-pointed ladder,” right? That brings that word back, but now it’s sleep rather than labour. His “long sleep, as I describe it coming on,” and what a great piece of ambiguous syntax.

|

|

|

William Emison would chew on this line, right? Because the “as” is both comparative and temporal at the same time, in that his long sleep at the moment that I am describing it is coming on, and as a comparison that I can’t quite make, or just some human sleep. And human sleep, the joke of this poem, is not quite sleep. It’s, you know, psychic rehearsal over and over again. |

| (00:25:19) |

Michelle Levy |

And, to go back to that idea of recognition, there is something about the physical exhaustion that launches him into this more mystical semi-sleep, un-sleep space, which I find interesting too because it’s almost like he’s, you know, I think about like an over-exhausted to toddler, right? Who can’t settle for themselves? |

| (00:25:43) |

Susan Wolfson |

He’s done it all day, and of course, this is every day. You don’t just have one day when you pick apples, right? This is a seasonal chore.

|

|

|

“And there’s a barrel that I didn’t fill / Besides it, and there may be two or three / Apples I didn’t pick upon some bough. / But I am done with apple-picking now.”

|

|

|

That does sound like an existential proclamation. And yet there’s this sense that there is just too much and that he is in default, that he has broken a contract to get every damn apple. Even those prepositions, “after apple-picking,” that it almost, by the time you’re at the end of the poem, “after” has this sense of going after, I mean, of, in other words, of pursuing almost as a poetic subject. It’s the poetic sequel as well as the temporal sequel. But after apple-picking, with apple-picking, I’ve had too much of apple-picking. When a phrase gets repeated three times, it’s, it’s not done with, it’s – |

| (00:27:02) |

Michelle Levy |

And I’m thinking through your discussion and listening to you recite some lines that are very different from Keatsian’s wonder at the kind of bounty of the harvest, right? There’s a kind of exhaustion. He’s overwhelmed. |

| (00:27:19) |

Susan Wolfson |

Keats is not labouring. He’s not part of the labour. Yeah. He’s not part of the harvest force. So until then until, what is it? I don’t have it. Oh, I should have it memorized. This is sort of a moment that just is for Keats; the joke is you think it’s gonna go on forever.

|

|

|

So, “To bend with apples the moss cottage-trees, / And fill all fruit with ripeness to the core; / To swell the gourd, and plump the hazel shells / With a sweet kernel; to set budding more, / And still more, later flowers for the bees, / Until they think warm days will never cease, / For summer has o’er-brimm’d their clammy cells.”

|

|

|

It’s Keats’ joke about this moment that seems infinite but isn’t. He’s looking at a world that is just still burgeoning and producing life. That’s a very different kind of autumn genre from the labour genre. The other thing about companies being fruitful and multiply is that you have now entered into a world of hard daily labour, which will never be over. That’s the penalty of having lost Eden because of an apple. So, that sort of patched into this too. Not with the world of sin but this is the world of labour. |

| (00:28:41) |

Music |

[Intrumental music begins to play in the background.] |

| (00:28:59) |

Michelle Levy |

So I’m wondering if it would be a good idea to end with you asking you to read the poem, and then maybe we can just pick up any threads that come out of that reading. Anything that we haven’t discussed. But it would be lovely to hear your recitation. |

| (00:29:17) |

Susan Wolfson |

Yeah, part of it is that the slow time of reading and of immersion in the labour is something I would kind of want to bring to this, in comparison to, say, Frost’s seeming interest to get from the beginning to the end as efficiently as he can. So I’ll read it and see what you think. |

| (00:29:44) |

Susan Wolfson, reading “After Apple-Picking” |

After Apple-Picking.

|

|

|

“My long two-pointed ladders sticking through a tree / Toward heaven still, / And there’s a barrel that I didn’t fill / Besides it, and there may be two or three / Apples I didn’t pick upon some bough. / But I am done with apple-picking now. / Essence of winter sleep is on the night, / The scent of apples: I am drowsing off. / I cannot rub the strangeness from my sight / I got from looking through a pane of glass / I skimmed this morning from the drinking trough / And held against the world of hoary grass.” |

| (00:30:31) |

Susan Wolfson |

“It melted, and I let it fall and break. / But I was well / Upon my way to sleep before it fell, / And I could tell / What form my dreaming was about to take. / Magnified apples appear and disappear, / Stem end and blossom end, / And every fleck of russet showing clear. / My instep arch not only keeps the ache, / It keeps the pressure of a ladder round. / I feel the ladder sway as the boughs bend. / And I keep hearing from the cellar bin / The rumbling sound / Of load on load of apples coming in. / For I have had too much / Of apple-picking: I am overtired / Of the great harvest I myself desired. / There were ten thousand thousand fruit to touch, / Cherish in hand, lift down, and not let fall. / For all / That struck the earth, / No matter if not bruised or spiked with stubble, / Went surely to the cider-apple heap / As of no worth. / One can see what will trouble / This sleep of mine, whatever sleep it is. / Where he not gone, / The woodchuck could say whether it’s like his / Long sleep, as I describe it’s coming on, / Or just some human sleep.” |

| (00:32:11) |

Michelle Levy |

I heard the rhymes [laughs] in a way that I didn’t hear before. “Bough,” “now,” “all in all,” I mean, they really are punctuated. |

| (00:32:21) |

Susan Wolfson |

And the repetitions that roll up with the rhymes, too. Yeah, I think that those are part of it. That’s the kind of pulsing or rhythm of the mind of a poet in composition, is that you are picking up words as words for their sensuous value, as words.

|

|

|

And rhyme and meter are one way to bring that value to language. That’s even the sort of the particular local knowledge of knowing the difference between stem end and blossom end. Now that’s a good case of something. If you think about it, you realize that’s exactly why you can tell that difference. It’s a stem, oh yeah, therefore the flower was there, and the fruit grows up behind the flower.

|

|

|

But that’s a sort of casual local speak that may not be the literacy of every reader, and you kind of have to meet Frost halfway just to have the mind of Frost, that you know that difference. So that’s the sort almost, that’s one of those cases where you almost know, and then, you know, as soon as someone says it to you, |

| (00:33:41) |

Michelle Levy |

Yeah, it’s a beautiful description, and you get that repetition within the line that echoes. There are so many apples, but yet there’s this particularity about each apple. Each apple has this pattern of the two different ends, but each apple is different. |

| (00:34:00) |

Susan Wolfson |

And “every fleck of russet showing clear.” That’s the language of someone who’s looking at the apple, the way he looked at that pane of glass. Each apple is a sort of event for him. |

| (00:34:13) |

Michelle Levy |

And you did a lovely job of slowing, really slowing down at the end, to really linger over those last couple of lines. |

| (00:34:22) |

Susan Wolfson |

Yeah, |

| (00:34:23) |

Susan Wolfson |

Well, there’s a sort of point of sleep where language begins to come minimal. But I still think that comparison to the woodchuck is just a hilarious piece of wit. It’s almost tonally inappropriate that he could have just said the woodland bear or something like that. There’s something he could fit in two other syllables of the brown bear. But, the idea that this creature of labour, whose very name comes from his labour is, I just think, hilarious, that he gets to sleep, |

| (00:35:05) |

Michelle Levy |

And as you said, there’s a slight touch that even though we have the ladder pointing towards heaven, and you have this invocation of the fall, as you say, he doesn’t quite take us there. It’s, he’s – |

| (00:35:20) |

Susan Wolfson |

Yeah [overlapping] |

| (00:35:20) |

Michelle Lee-ve |

He’s provoking us. He’s suggesting it, but ultimately, is that what the poem’s about? Or is it – |

| (00:35:26) |

Susan Wolfson |

Kicking an apple, a ladder pointing towards heaven, which means the sky. But there’s a whiff of the metaphysical there. That is part of the kind of dream world, too, that the one thing the ladder isn’t doing is it’s not Jacob’s ladder. You’re not going up that ladder to heaven. So it’s almost like a joke that this ladder is part of the instruments, part of the tool shed of labour.

|

|

|

And you know, it does come with a slight default or transgression, a barrel I didn’t fill. But that’s not on the level of sin. If anything, if you’re trying to work this out on the map of Eden, you’re in trouble of picking more apples as your salvation. It’s almost a joke about that too. |

| (00:36:18) |

Susan Wolfson |

I just kind of like this poem for the way in which ordinary language becomes a kind of record of memory, of dreaming, of labour, of self-ironizing and existential self-reckoning in relation to poetry that is embedded in multiple traditions from Genesis to Keats, to romanticism, to poems of labour, and yet doesn’t insist that you do the math. When you add this up, all those aspects of human language and human poetic tradition kind of impinge or press on your sense of how to read this poem, how to understand this poem. And then part of reading a poem like this, that’s loaded with temp, station for you to do that kind of work, is to feel the temptation and then feel that that’s not really what’s going on. That this isn’t an allegory of a fall of man. |

| (00:37:29) |

Susan Wolfson |

I mean, the New England word for autumn, Keat’s poem is too autumn, not too full, but the New England word, the American word for that is fall. And so that also sort of comes in as a kind of tacit understanding that we don’t have a fall without the fall. But it’s not about that. It’s just about the kind of every day, kind of mulling that can make magnified apples appear and disappear. It can be magnified. It takes possession of your mind. It’s surreal, it’s real. It’s a dream; it’s waking. It’s just great. It’s just a great sort of experience going from word to word and line to line. |

| (00:38:13) |

Michelle Levy |

Thank you so much. It’s been a wonderful conversation, and I really appreciate you taking the time to work through the poem so thoughtfully with me. |

| (00:38:25) |

Susan Wolfson |

Well, it was so much fun. |

| (00:38:25) |

Music |

[Instrumental music starts playing] |

| (00:38:41) |

Maya Schwartz |

Hi there. It’s Maya, your co-host for today’s episode. For part two, I interviewed my professor, Stephen Collis. |

| (00:38:49) |

Stephen Collis |

I’m Stephen Collis, a poet, and I teach poetry at Simon Fraser University. |

| (00:38:53) |

Maya Schwartz |

We sat down in his office at SFU to chat about the poem “Seafarer” by William Carlos Williams. I began our conversation by asking Steve why he chose this poem. But first, here’s the Caedmon recording of Williams reading the “Seafarer.” |

| (00:39:12) |

William Carlos, recording for Caedmon, part of the “The Poets of Anglo-Saxon England” collection, 1955 |

“The sea will wash in / but the rocks – jagged ribs / riding the cloth of foam / or a knob or pinnacles / with gannets- / are the stubborn man. / He invites the storm; he / lives by it! / instinct with fears that are not fears / but prickles of ecstasy, / a secret liquor, a fire / that inflames his blood to / coldness so that the rocks / seem rather to leap / at the sea than the sea / to envelope them. They strain / forward to grasp ships / or even the sky itself that / bends down to be torn / upon them. To which he says, / It is I! I am the rocks! / Without me, nothing laughs.” |

| (00:40:15) |

Maya Schwartz |

Why did you choose this poem? I sort of gave you two to choose from. Have you read it before? What, sort of initially struck you? |

| (00:40:23) |

Stephen Collis |

I don’t remember having read it before. So that may be part of the attraction. Again, that a poet I’m reasonably familiar with, if not, have studied exhaustively. So it was just one I don’t really know of. And, but it’s everything that attracted me to it is in the reading of it. In the way he reads it, which is extraordinary. I don’t know. Should I just jump right into why that is because that’s for the next question? Because it’s the quality of his voice, which I knew it had that quality from maybe other recordings, I guess, and it’s kind of a known thing, if people know about that kind of poetry, they know that he had a funny voice, i.e. it’s relatively high pitched. It’s kind of fragmented and rough and ragged, and we have recordings of him as an old man, right? |

| (00:41:08) |

Stephen Collis |

Because this is the 1940s or fifties or something like that, so he’s probably in his seventies. But I think he always sounded that way, [laughs]. He, as a younger person, kind of sounds like some sort of grandmother or, I mean, doesn’t he? So I kinda like that. I like that there’s a contrast in it between the kind of vaguely male-ish sexuality that’s in it, which he’s sort of known for, too, I guess. And this crackly grandma voice, which is kind of funny, [laughs].

|

|

|

So one, that’s one thing, the quality of his voice being so fragile and kind of unattractive, right? You don’t wanna listen. So, nonetheless, in that kind of ugliness of his voice, seeming fragility and vulnerability, I’m kind of attracted to that aspect of it.

|

|

|

Then the other thing is the excessive pausing, which is, I love when a poet reads their line breaks or leans into their line breaks in such a way that he really does here. That first line, you just, you get the first line, you feel like you wait forever for the second line. Hang in there [inaudible], and I know there’s more, buddy. What’s it gonna be? What’s, what’s coming here? That’s fascinating to me, too. |

| (00:42:18) |

Maya Schwartz |

The pauses line up with the line breaks. |

| (00:42:20) |

Stephen Collis |

For the most part. They don’t completely, and I think poets, there are poets who never read their line breaks, right? That’s not the point. They scoot right through them. Maybe that’s because there’s a narrative element, or whatever, or it’s just the lines aren’t enjambed. There isn’t a natural kind of pausing, a phrase that the line breaks.

|

|

|

Then there are poets who, whether or not it’s enjambed, they like to hang on the line break. And I tend to like that. I tend to like the kind of pressure it puts on the voice and the reading when you have that tension there; it kind of goes back to that thing like what T.S. Eliot said about, was it T.S. Eliot? No. Who was it? Robert Frost says that writing poetry without rhymes is like playing tennis without a net or something like that. |

| (00:43:08) |

Stephen Collis |

A rhyme meter is like playing tennis without a net. And there’s just some, I get what he means. Like, I think it’s, I definitely don’t write rhyme and metered poetry myself, but, and I tend to prefer poetry that isn’t rhymed and metered, but unless I get what he’s saying, he’s saying is, you need this sort of abstract tension framework to work against.

|

|

|

And that’s what line breaks are providing here. Just there’s this frame of the short lines going down the page, and the poet is pushing against them every time. So, a couple of times, he does push right through them and runs under the next line or two pretty quickly, but it’s rare in this poem. And he mostly pushes right up hard against those line breaks, and you really feel him pushing them. |

| (00:43:47) |

Maya Schwartz |

Did you notice anything else about the way that Williams read this poem? Like his accent or inflection tone, speed, or emphasis? |

| (00:43:56) |

Stephen Collis |

Totally. There’s something in the accent, too, which, for us sitting here in Canada, maybe is just generically American about it. But then there’s a wonderful emphasis on certain words. There are the words he just draws out, right?

|

|

|

Like he, obviously the first line, but individual words like “instinct,” right? “He invites the storm; he / lives by it! / Instinct,” and he kinda says it like that; he just pulls on that word, which is fascinating. And no real reason for it, I don’t think. It’s not like, it’s like a heavy syllable, a weirdly metered kind of word. But he really leans in; he does that a couple of times, “ecstasy,” maybe a little bit, and “liquor,” right? “A secret liquor,” basically really getting the “K” sounds. So he’s playing to the score he’s written for himself.

|

|

|

He’s really leaning into those notes you can really play hard and draw out in the reading of it, and it does build toward the ends, right? You get that exclamation mark near there, the end, but he’s, or get too near the end. But his voice does start to rise in volume, released at the end as he tries to bring it to this dramatic moment where the rocks speak. You know? “It is I!” [Laughs] |

| (00:45:14) |

Maya Schwartz |

That’s a hilarious reading. |

| (00:45:16) |

Stephen Collis |

[Laughs] I know. It really is. |

| (00:45:17) |

Maya Schwartz |

And then it settles back down again, “Nothing laughs.” |

| (00:45:20) |

Stephen Collis |

Yeah. Which is such a weird last line in the poem, right? Like, “nothing laughs,” I don’t get the, I walk by thinking I don’t get the joke. Was I supposed to laugh? |

| (00:45:29) |

Maya Schwartz |

Yeah. |

| (00:45:29) |

Music |

[Instrumental music starts playing in the background] |

| (00:45:35) |

Maya Schwartz |

Do these sorts of different emphases change the way that you interpret the poem? |

| (00:45:40) |

Stephen Collis |

Yeah, that’s a good question. To some extent, I think they do. And a lot of that, to me, rides on those two words at the end of a line. It’s probably the longest line on the page, but it’s, they strain, are the words, I would say.

|

|

|

And, this definitely draws our attention to the straining, the tension in the poem, like literally physical tension that he’s playing with, really heavily emphasizing those line breaks, really drawing out the pauses at the end of his lines, or leaning into a word like “instinct,” which just draws out into this much larger space than it should be on the page. That those words they strain really leap out at me as marking this, or reminding me that this is a poem about this kind of tensions that the writer seems to be really interested in. I mean, they’re elemental, you know, it’s sea and land, but they’re encapsulated in his voice and how he reads the poem. |

| (00:46:40) |

Stephen Collis |

Do you think that listening to the voice of the poet brings us closer to Williams himself? |

| (00:46:46) |

Maya Schwartz |

Well, that is pretty wonderful. I love poetry readings. I know a lot of people will say this, it still feels like it’s a necessary part of poetry, that it’s being read aloud by the author. And you always notice something. If you’re familiar with a poem on a page and you have not yet heard the author read it, then you hear them read it. There’s always something revelatory to that. Sometimes disappointing, ii’s like “really? You’d read it like that?” And I don’t, I wouldn’t do that, or that interests me less now that you’ve done that to it.

|

|

|

But it is, there’s a quality of, well, it’s got to do with body, embodiment, I think. And poetry to me is very embodied language. And you need to be in the body that felt, heard, breezed, spoke it the way they felt they should or needed to, or would on that occasion. I think that’s significant. So there is, you’re getting a sense of William’s body there, of his breath and his attention and his voice. And, again, that’s what all those heavy line breaks do too. They reemphasize that straining of the voice to get outta the body and take up that oral space of the room around it. |

| (00:48:00) |

Maya Schwartz |

The founders of Caedmon have said that their goal was to capture as much as possible what the poets heard in their heads as they wrote. |

| (00:48:08) |

Stephen Collis |

Nice. |

| (00:48:09) |

Maya Schwartz |

And I think that, yeah, you did a good job of signing up what we gained from knowing what it sounded like to them. And there’s also sort of a challenge, or like a, there’s also a benefit to not knowing, I think so, too. Is there anything that you think is particular to this poem that makes it well suited for that recording? And it might explain why Williams would choose to read it and have it be recorded? |

| (00:48:36) |

Stephen Collis |

So it might have been a poem that, he just liked how this one played when he read it a lot. He is like, I like how I get to play with the tensions and line breaks here, but he works in his ear or in his body, and, then there’s the, does this poem ring or chime off of, or evoke those other seafarer poems in some way? And then maybe he was enjoying that. |

| (00:48:58) |

Maya Schwartz |

I asked Steve to say more about how he thought Williams might be evoking earlier seafarer poems. |

| (00:49:05) |

Stephen Collis |

Well, there’s such an interesting tradition there, because there’s the old English, Anglo-Saxon, really early poem, “The Seafarer” that is anonymous. We don’t know who composed it, but we have it.

|

|

|

And Ezra Pound did a translation of it in the very early 20th century at some point there. And Pound’s translation is interesting for a couple of reasons. Like he sort of trimmed off any Christian references in it and sort of made it more of a, I don’t know, kinda like a pagan poem, I guess.

|

|

|

But he really, really did work so hard to get that kind of Anglo-Saxon field poem via word choice and via alliteration, and really making sure it was like a chewy, deep resonant poem in the mouth as it were. But I was thinking that the Williams poem maybe has more to do with H.D. than Pound. The three of those people, they knew each other since they were children, right? |

| (00:49:58) |

Stephen Collis |

Those three poets, they all went to school in Pennsylvania together, and maybe vaguely, they all – Pound dated H.D. for a tiny while. Maybe Williams dated her for a tiny bit too. So it’s, this whole kind of weird sort of high school romance thing behind their poetries’ love triangle. I know, it’s pretty hilarious. And they remain kind of frenemies their whole lives, right? And were very aware of each other their whole lives. So H.D. becomes famous as the quintessential imagist in that era, the poems are these really paired down small, compressed, refined visual entities.

|

|

|

But, so if, can I read you H.D.’s, like five or six lines long? This is the one I think of when I think of Williams’ “Seafairer”, I don’t hear Pound’s so much. I hear this poem, called “Oread,” which is like a sea nymph or a sea spirit of some kind. “Whirl up, sea— / whirl your pointed pines, / splash your great pines / on our rocks, / hurl your green over us, / cover us with your pools of fir.” This exact same scene as it were, where Williams poems is set where the sea and the land meet. But they’re also similarly kind of interpenetrating and taking on each other’s qualities. So in the H.D. poem, it’s really clear that the sea has land-like qualities. The sea has pines, the sea has rocks, right? So there’s this really kind of meshing of those, these supposed opposites. They do a bit of that in the Williams’ poem too. |

| (00:51:33) |

Maya Schwartz |

They both seem to have this, almost like they’re talking to the other thing in the poem, like a conversational — |

| (00:51:38) |

Stephen Collis |

Yeah. Yeah, exactly. Yeah, for sure. Yeah. So, , I think, I love that word, “ganet.” [Laughs]

|

|

|

William asking there, he kind of sounds like a ganet. I don’t know what a ganet sounds like for sure. But Williams kind sounds like a seabird. So there’s a little bit of that, but I think they’re both interested in this kind of, dare I say, kinda like a dialectical tension between these opposites sea and land. I think Williams is keyed more into a gendered opposition too.

|

|

|

He, in the “Seafairer,” he doesn’t refer to the sea as feminine, although that’s a, maybe, a traditional trope. But he definitely refers to the rocks as masculine. The rocks are a “he,” and they are given his voice to pronounce things at the end. And that feels to me kind of like, a Rejoinder Williams would have for H.D. I’m responding to your sea-ish poems and picking up that same imagery and tropes, but I’m kind of reasserting a kind of maleness. He’s less interested in, let’s say. |

| (00:52:47) |

Maya Schwartz |

Yeah. Let’s talk about the, the last line. Yeah. how do you interpret that? “Without me nothing laughs.” |

| (00:52:56) |

Stephen Collis |

I mean, there’s this a this is where I was, I guess I’m getting with the gendered thing. There’s this kind of authority the rocks are claiming over the sea.

|

|

|

There it is. I, I who I’m the rocks without me, nothing laughs, you know, laughing is such an instinctual and again, embodied thing that we often don’t have a lot of control over. [Laughs] [Maya agrees]

|

|

|

It’s something that just ripples and bubbles up like the sea perhaps might be going too far here [laughs]

|

|

|

But the voice, the speaker of this poem is asserting this control. But it’s a weird thing to focus on, you know, to go from this, the awesome power of the sea to like, you know, no giggling. Yeah, you dare giggle in front of me until I tell you it’s okay to giggle here. Yeah. It’s, it’s, yeah. I don’t know. It’s, do, do you have a sense, do you have a take on that last line? |

| (00:53:46) |

Maya Schwartz |

I don’t know. I feel like especially listening to him say it, but it sort of seems like it knows that things laugh without him. |

| (00:53:58) |

Stephen Collis |

Yeah. Right behind his back. |

| (00:53:59) |

Maya Schwartz |

Yeah. It’s sort of like a – |

| (00:54:02) |

Stephen Collis |

Yeah. |

| (00:54:02) |

Maya Schwartz |

Like he has to say it, but it is still got this sort of like awareness. |

| (00:54:07) |

Stephen Collis |

I mean, it’s not a punchline as a word. But I wonder if there is just a tiny little wink and nudge and irony there.

|

|

|

Just laughter, you know? We’re talking about here. It’s not, it’s not this huge elemental, godsend storms and powers that are being invoked. Just a little self-control. Because it does have a nice book ending to the poem in general. Like, so you, especially the way he reads it, right. The sea will wash in and you get this infinite seeming pause before you get, but the rocks is a, there’s a real hard turn in the poem there to rocks. And we come back to it is, I own the rocks at the end, but again, laughter’s not what you’re expecting at this point. No, it isn’t. It’s either a super assertion of power, but like, I even demand control of your you know, inadvertent muscle reflexes, or is it just, and maybe it’s both probably often in poetry, it’s a little bit of both. |

| (00:55:10) |

Stephen Collis |

This sort of pathetic drop into just, eh, it’s just, you know, just don’t laugh at this. Just don’t take this as a joke. Right. Even though we all know it’s kind of a joke that I’m, that I’m striking a big pose here. Yeah. And my outrageous exaggerated pauses and jam is all part of that, you know, weirdness. That’s nothing about reading line breaks. What’s weird about leading rhyme breaks is, you know, sure, we hesitate and stumble when we speak, but to do it in this kind of almost rigid sense to always be pausing in your speech is drawing us an incredible attention to the performance of speaking words.

|

|

|

So there is a little bit of laughing at that, at the end, isn’t this ridiculous? And I wonder what that relationship would’ve been like in terms of like, did they just go, “oh, William Carl Williams is gonna read at nine/six, let’s go ask, see if we can record it”.

|

|

|

[Soft music starts playing in the background]

|

|

|

Is that, or I wonder what’s going on there? What are the relationships? |

| (00:56:09) |

Maya Schwartz |

They had both just graduated from Hunter College. And they had degrees in Greek Uhhuh, and they heard that Dylan Thomas was going to read Of course. And they were like, “it’d be sick to record ’em.”

|

|

|

I don’t know where they got that idea from. And they went to, they didn’t record him at the “Y,” they tried to get in contact with him, and it was like a series of passing notes.

|

|

|

And then they tracked him down to the Chelsea Hotel, [Stephen says “Oh my God.”] and they sort of used his drinking to, I think one of them called, they couldn’t get in touch with him, and one of them called him at like 4:30 in the morning when he was just coming back from [Stephen: Get out] a night out and, and [Stephen: drunk as hell] he agreed. And then he missed all there. |

| (00:56:47) |

Maya Schwartz |

Finally he showed up and he was, they were drinking “madame” in a bar. And he agreed to, for them to record some of his poems, and he gave them a list and it wasn’t enough. They wanted something for the B-side. And he was like, “oh, I have this story: child’s Christmas in Wales.” |

| (00:57:07) |

Stephen Collis |

Oh, that’s what it is. |

| (00:57:08) |

Maya Schwartz |

And it was the popularity of that story. [Overlapping, Stephen: Yeah.] Which never would’ve been what it is without them recording it. And I guess it was a selling factor, and they were from having him able to get other people. I think they got Lawrence Olivier to read. |

| (00:57:22) |

Stephen Collis |

Cool. It’s got a great history of that project, doesn’t it? |

| (00:57:26) |

Maya Schwartz |

Mm-Hmm. |

| (00:57:26) |

Music |

[Instrumental music starts playing in the background] |

| (00:57:31) |

Maya Schwartz |

In the interview with Wachtel, Mantelle and Holdridge strongly resist the notion that they discovered spoken word poetry. But they do acknowledge the role that Ceadmon played in not only creating an industry for recorded literature, but also in changing the way that poetry is written. |

| (00:57:48) |

Marianne Mantell, Writers & Company Interview, 2002 |

I think that when we began in February of 1952 with Dylan Thomas, we were not creating the notion of spoken poetry, obviously poetry, and its, its reading anate the discovery of writing, or the invention of writing, I should say, by a long time.

|

|

|

It was poetry that people used to remember their history or to recreate their history as it were. Homer wasn’t written, Homer was spoken or sung. But I think that over the generations, with the particularly, with the invention of type, and the profusion of published books, the kind of disappearance of the sound began to take over.

|

|

|

And although there was a movement towards poetry readings, which Dylan was part of, it was perhaps a symbiotic relationship. The market was there for our records, and the records created the market. And I do believe that once Caedmon became part of the mainstream, certainly of literary life, I think the writing of poetry changed.

|

|

|

I don’t think that poets from the late fifties wrote in the same way they were too much aware of the prevalence of, of recorded, or at least of spoken poetry. |

| (00:59:21) |

Barbara Holdridge, Writers & Company Interview, 2002 |

Really, at least two generations have grown up knowing Caedmon records. They, strangers come up to me all the time and tell me what an impact those recordings made in their lives. And this was really the beginning of the spoken word revolution. This multimillion-dollar audio industry that we have now, owes its inception to two girls recording literature who felt that it was a contribution to understanding. |

| (00:59:52) |

Music |

[Opera music starts playing] |

| (01:01:50) |

Katherine McLeod |

[Low electronic music plays] The SpokenWeb Podcast is a monthly podcast produced by the SpokenWeb team as part of distributing the audio collected from and created using Canadian literary archival recordings found at universities across Canada.

|

|

|

This month’s episode was produced by Maya Schwartz and Michelle Levy. The SpokenWeb podcast team is made up of supervising producer Maya Harris, sound designer, James Healy, transcriber,Yara Ajeeb, and Co-hosts Hannah McGregor and me, Katherine MacLeod.

|

|

|

[SpokenWeb Podcast Theme Music begins in background] To find out more about SpokenWeb, visit spokenweb.ca and subscribe to SpokenWeb Podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you may listen. If you love us, let us know. Rate us and leave a comment on Apple Podcasts, or say “hi” on our social media at Spoken Web Canada. Stay tuned to your podcast feed later this month for shortcuts with me, Katherine McLeod, short stories about how literature sounds.

|

|

|

[SpokenWeb Podcast Theme Music fades and ends] |