| 00:00:05 |

SpokenWeb Intro Song |

[Oh, boy. Can you hear me? Don’t know how much projection to do here.] |

| 00:00:18 |

Hannah McGregor |

What does literature sound like? What stories will we hear if we listen to the archive?

Welcome to the SpokenWeb Podcast, stories about how literature sounds. [Music fades]

My name is Hannah McGregor– |

| 00:00:36 |

Katherine McLeod |

And my name is Katherine McLeod. |

| 00:00:39 |

Hannah McGregor |

One of my favourite genres of SpokenWeb podcast episodes is the behind-the-scenes look at the material labour involved in creating, preserving, and studying literary sound.

In past episodes, we’ve talked about the work of transcription, the affordances of sound design, and the messy business of wading through archival collections.

In this new episode, producers Natasha D’Amours, Michael MacKenzie, Sarah Freeman, and Xuege Wu take us inside one of the most common kinds of work that research assistants, working on the SpokenWeb project, participate in: timestamping. |

| 00:01:19 |

Hannah McGregor |

Drawing on the insights and questions that have emerged from their own engagement with timestamping as a practice, the producers bring together a panel of three SpokenWeb researchers—Jason Camlot, Tanya Clement, and Mike O’Driscoll—for a roundtable discussion. Together, they explore epistemologies of time, the subjectivity of annotation practice, and the role of controlled vocabularies, concluding that timestamping is always an interpretive act grounded in choices about meaning, representation, and access. |

| 00:01:57 |

Hannah McGregor |

This is Season 6, Episode 7 of the SpokenWeb podcast: Sound & Seconds: A Roundtable on Timestamping for Literary Archives. [SpokenWeb theme song plays and fades] |

| 00:02:17 |

Sarah Freeman |

[Upbeat instrumental music plays in the background]

What does it mean to listen to literary history? Not just to hear voices from the past, but to make them searchable, structured, and accessible.

For SpokenWeb, timestamping goes beyond marking moments in an audio recording—it transforms sound into something legible, curates literary events, and preserves ephemeral voices. Each timestamp isn’t just a data point; it bridges raw audio with structured metadata. By logging sonic events alongside their timecodes, we create a detailed map of each recording. These timestamps are then transferred to a public-facing platform where users can engage with the archive, clicking on a timestamped event to jump directly to that moment. |

| 00:03:10 |

Sarah Freeman |

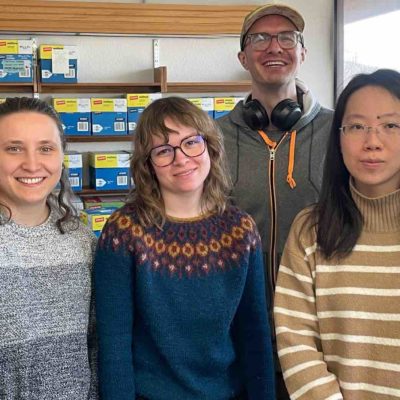

I’m Sarah Freeman, a student research assistant with SpokenWeb at the University of Alberta. I joined my fellow research assistants, Natasha D’Amours, Michael MacKenzie, and Xuege Wu, to take a deep dive into timestamping. After all, for most of us, our first task with SpokenWeb was timestamping—carefully listening to archival audio to identify and describe sonic events using a controlled vocabulary.

This work sits at the intersection of archival practice and digital humanities. But why does it matter? How does timestamping shape the preservation and curation of literary sound? As Phase One of SpokenWeb nears its conclusion, we turn to three scholars who’ve shaped this discussion: Jason Camlot— |

| 00:04:09 |

Jason Camlot – Audio Clip |

[Click-whirr] Timestamps have existed since the beginning of time. [Click-whirr] |

| 00:04:14 |

Sarah Freeman |

Mike O’Driscoll– |

| 00:04:16 |

Mike O’Driscoll – Audio Clip |

[Click-whirr] I connect it to a whole series of print-based technologies and responses to an overflow of print information. [Click-whirr] |

| 00:04:25 |

Sarah Freeman |

And Tanya Clement– |

| 00:04:27 |

Tanya Clement – Audio Clip |

[Click-whirr] Time is a perspective, and a timestamp can be off, given a perspective. [Click-whirr] |

| 00:04:34 |

Sarah Freeman |

In this episode, we bring you a roundtable conversation moderated by Michael McKenzie that dives into the intellectual, technical, and archival stakes of timestamping.

Let’s press play [sound of needle dropping on record] and immerse ourselves in the layered sounds of literary preservation. |

| 00:04:55 |

Michael McKenzie, Audio Clip |

[Soft instrumental music plays]

Okay, so if everyone could just clap on three. Okay, one, two, three—[one clap]

[Laughter]

Yeah, that was bad. That’s the worst timestamp ever. [Click-whirr] |

| 00:05:08 |

Michael McKenzie |

My name is Michael McKenzie. I’m a third-year PhD student at the University of Alberta, in English and Film Studies, and I’ll be moderating today’s roundtable on timestamping. [Soft instrumental music continues to play] |

| 00:05:26 |

Michael McKenzie |

[Click-whirr followed by a beep]

Okay, so, because we only have an hour, I’ll just introduce the first question. So, timestamping is one of the chief places where many graduate students working with SpokenWeb put in our hours. Our podcast teams experience has brought us to think about timestamping in part like literary indexing practices, something that literature has long been subject to by scholars through, for example, the table of contents. |

| 00:05:52 |

Michael McKenzie |

Timestamping, however, is distinct and that it applies the practice of indexing to durational media such as video and audio by cutting it up into smaller periods of time that can easily be searched and studied. Among our team, we’ve begun to notice the ways timestamping exceeds these definitional boundaries to blur the lines with transcription, annotation, introduction, or summary. |

| 00:06:18 |

Michael McKenzie |

There seems to be a lot more happening with timestamping than its modest reputation suggests.

So given the diversity of institutions and styles across SpokenWeb, we’re so glad to have all of you here and your expertise as leaders in SpokenWeb to help us think through these problems and challenges further.

So maybe as a point of departure, you might all attempt a definition for timestamping, and explain what timestamping is or has been for you, and perhaps a defining moment for when you started to think about it seriously. [Upbeat music] |

| 00:06:55 |

Jason Camlot |

I wouldn’t mind going first because I I took it very seriously and began to think about what is that question: what is a timestamp? |

| 00:07:03 |

Sarah Freeman |

[Click-whirr] Jason Camlot, professor at Concordia University and PI [principal investigator] of SpokenWeb, specializes in literary sound recordings and digital artifacts. As the originator of the SpokenWeb project, he’s been around since the very first recordings were digitized and timestamped. [Click-whirr] |

| 00:07:23 |

Jason Camlot |

And so, I’d like to share a few theses on timestamps that I’ve just developed, right? The first one I want to mention is that, as I was thinking about this, timestamps have existed since the beginning of time. I think that’s an important place to start.

Timestamps within digital systems, in that sense, represent one manifestation of a long history of temporal measurement—timekeeping and its mobilization for meaning-making. There’s a lot of scholarship on ancient timekeeping, both in relation to the seasons and in the development of mathematics as a way of producing a calculus of time for various purposes.

So, the conception of time in terms of measurable units and ideas of temporal precision goes back very far in history. Then I started thinking about Hayden White’s work from the 1980s on history, particularly the distinction between annals and historical narrative. I think that’ll be interesting to think about. [Click-whirr] |

| 00:08:22 |

Sarah Freeman |

Here, Jason is referring to the American theorist of history, Hayden White.

White introduced medieval annals—lists of notable events organized by year—as alternatives to homogenizing historical narratives. Like timestamps, annals link moments in time to events that occurred within them, albeit on a much larger scale. A set of timestamps may be similar to annals, attributing equal importance to disparate threads of a sonic event.

Timestamps may also emphasize similarities across a sonic event, creating a unified narrative of that event—but more often, timestamps do a little bit of both. [Click-whirr] |

| 00:09:06 |

Jason Camlot |

Because, you know, annals, in a way, represent another form of historical timestamping, right? They’re just lists of dates and things that happened. But I think there’s an interesting relationship—perhaps even a tension. I’d probably want to think of it as a dialectical relation between the timestamp as a demarcated moment in time’s unfolding, and the larger narrative account within which that timestamp gains significance.

So that’s the first thesis. |

| 00:09:32 |

Tanya Clement |

I’m going to play devil’s advocate here. [laughs]

I’m going to say that a timestamp is more like a page number—a way to reference something else you’re interested in. [Click-whirr] |

| 00:09:48 |

Sarah Freeman |

Tanya Clement, an associate professor at the University of Texas, brings leading expertise in digital sound technologies, data searching and visualization in relation to literary audio and software development for sound pattern searching. [Click-whirr] |

| 00:10:06 |

Tanya Clement |

Because the timestamp itself is only relevant to the extent that it points you to a concept, an idea, or an event. The way we’re working with timestamps in this project is to indicate or index an annotation. That annotation could be a transcript, a note, or a description. But the timestamp itself is significant only insofar as it points to a place on the material medium. This doesn’t mean it’s insignificant as a material aspect of that medium, but I don’t think it bears significance without an attached annotation—without a reason. |

| 00:10:58 |

Mike O’Driscoll |

Yeah, I’m going to take a slightly different approach. I think of timestamping as a technology of information management. [Click-whirr] |

| 00:11:07 |

Sarah Freeman |

Michael O’Driscoll, professor at the University of Alberta and co-applicant of SpokenWeb, contributes deep knowledge of poetry and poetics, material culture, and archive theory. [Click-whirr] |

| 00:11:20 |

Mike O’Driscoll |

And I connect it to a whole series of print-based technologies and responses to a deluge of print matter in the mid-19th century—responses that led, for example, to the formation of the Royal Indexing Society in the UK. This included the standardization of cataloguing systems in libraries, a whole suite of archival management techniques, and other methods for handling an overflow of printed information at the time. One of the ways Western society responded to this was by developing a system of codified, standardized, and professionalized information management technologies.

These systems evolved over time. And with the emergence of durational media in the late 19th and 20th centuries, we also began to require new ways of counting and organizing time within those media. |

| 00:12:19 |

Mike O’Driscoll |

And so, like Tanya, I would probably connect those to various kinds of print technologies;you mentioned page numbers, but I think of them more predominantly as a form of table of contents—a form of indexation, a way to get inside the black box of analog and digital recordings in order to discern what those contents might be in a practical and manageable way, in advance of actually engaging those as listening events. |

| 00:12:51 |

Jason Camlot |

Just to reinforce– [Click-whirr] |

| 00:12:53 |

Sarah Freeman |

Here’s Jason Camlot jumping back in. This type of spontaneous exchange is part of the roundtable format, where anyone can speak up at any time. [Click-whirr] |

| 00:13:05 |

Jason Camlot |

The emphasis on print that both Tanya and Mike made—the page, the page number, the index—highlights the mirrored presence of the term “stamp” in relation to temporality, right in the phrase itself. I think it really underscores that way of thinking about the control of time, or the attempt to control something that is, by nature, probably less controllable, you know, by fixing it in some way or another—with a reference or an index—we attempt to make time manageable.

And I would just add to Mike’s point that so much of 19th-century print culture is periodical, right? It essentially divides itself into periods—whether it’s dailies, weeklies, or monthlies—each of which is a different measure of things happening within that span of time. So, the explosion of periodical literature in the 19th century is another strong manifestation of what Mike was talking about. |

| 00:14:11 |

Mike O’Driscoll |

Having said that, Jason, I also found that your recourse to early time mechanisms—timekeeping mechanisms—is really fascinating, because it’s true that everything from sundials to Stonehenge, to much else—to the pyramids—are devoted to ways of marking time. And that time is also, you know, connected to astrophysical observations and all kinds of other geological observations. And, you know, it maybe is a false heuristic to divide these things, because they are all technologies of temporal management in one way or another, and time is just one more form of information. |

| 00:14:52 |

Jason Camlot |

Despite Tanya’s opening rhetorical gambit, I did not take them to be in opposition to each other whatsoever. Actually, I think what all three of us have said is quite continuous with one another. |

| 00:15:05 |

Tanya Clement |

With one exception, though—I really, honestly, don’t see timestamps as a table of contents. I think it’s page numbers. In my mind, it really has very little information without an annotation attached. So, a table of contents doesn’t make much sense if you just have the page numbers; you have to say, like, what’s on those page numbers that you’re actually indexing. I think the same is true with information architectures—you know, just having numbered cells isn’t necessarily useful unless you know what they’re indicating.

I still think I’m being a bit of a devil’s advocate here, because I’m not giving that much importance or significance to the timestamp in and of itself without the attached—what I would call—the annotation. |

| 00:15:58 |

Jason Camlot |

I don’t see that as being different from, say, the annals, right? The annotation there is how the crops were that year, right? You know, whatever—it’s referring to something that happened. So in that case, the annotation and the reference point in time is an event. It might have been an event related to the weather, or crops, or some political event, potentially. You know, when annals mention kings—when they took the throne, etc.—those are all indexing events that happened.

One thing I really like about your pushback, though—because when this question about what is a timestamp? was asked to me and I sort of went back in time—is how much I realized that, as we move from ancient history and conceptions of temporality through analog media and its modes of marking time to digital media, a lot of that shift seems to be about the scale at which one is doing annotations, and the increasing degrees of precision—what Wolfgang Ernst calls micro-temporalities—as we move into digital media.

So, I think a table of contents versus a timestamp, or annals that are annual versus a timestamp of a 3-minute recording with 50 annotations—those are questions of temporal scale that I think are really interesting to think about in relation to timestamps. But personally, I see them as working on a continuum. |

| 00:17:29 |

Mike O’Driscoll |

One of the things I really liked that you said, Tanya, is that it actually invites us to make a finer distinction between the timestamp as simply the marking of time, and the annotation as the demarcation of content, or event, or evaluation, or summary judgment—whatever that might be—of that particular moment in time.

And by saying, “Oh, it’s like a table of contents,” I think I’m collapsing those ideas into one concept. And it sounds like you’re working to keep them as distinct—distinct activities or distinct forms of impression. [Soft instrumental music plays] |

| 00:18:14 |

Sarah Freeman |

As student assistants on the SpokenWeb U Alberta team, we see timestamping as a crucial intermediary step between digitizing reel-to-reel tapes and making them publicly accessible. |

| 00:18:28 |

Sarah Freeman |

We use close listening to identify when specific sounds occur in the recordings and sometimes conduct archival research to determine, for example, which poem a speaker is performing. This process results in metadata, such as the following timestamp: “From 0:01 to 1:01, Earle Birney performs his version of Kurt Schwitters’ ‘Ursonate’.”

In creating these timestamps, we’re not just listening to and analyzing the recordings—we’re transforming them into written data, effectively turning sound into another form of media. [Instrumental music plays and fades] |

| 00:19:10 |

Michael McKenzie |

The next thing I wanted to ask is: why should we think critically about timestamping? This question comes from a place of thinking about timestamping as something that might fly under people’s critical thinking radar. What kinds of things have you encountered that made you start to think critically about timestamping?

I have a list of examples here—everything from YouTube’s heat map algorithm, which shows how popular a video is at any given point along its time bar, to EKG (electrocardiogram) monitors that mark the rhythm of a heartbeat and any interruptions in it with beeps and squiggles. There are also the SETI Institute’s protocols for parsing sound from outer space to identify potential alien messages, and seismic monitors or lie detectors that give off sudden bursts of timestamping activity.

These are all examples with very specific goals and motives. Given the wide variety of things a timestamp can do, what brought you to start thinking critically about it? |

| 00:20:28 |

Tanya Clement |

So obviously, especially in the context of the examples you gave, timestamping can be done for a variety of reasons, and different people might choose to index a recording differently for a variety of purposes. What I find interesting, though, is that when you engage with something like timestamping—and you try to translate those timestamps across systems or datasets, or manipulate the data in the process of transposing it from one format to another—what you sometimes find is that the timestamp gets altered. It becomes a little less accurate, a little bit off.

And I think that does matter. I’m not sure if this is an exact response to your question, but it is something that feels closely related. |

| 00:21:24 |

Tanya Clement |

What comes to mind is that the act of timestamping reminds you that time can also be subjective. Especially because timestamping is inherently something that depends on a digital or electronic apparatus in some way, shape, or form. And those devices are calibrated according to different standards—different time zones, and many other variables. There’s also the question of precision: whether the timestamp goes to the thousandths of a second, or just to the milliseconds, or even less precisely. |

| 00:22:01 |

Tanya Clement |

So I think there is some space to consider whether we are actually thinking about timestamps—and if, as I’m proposing, we disambiguate timestamps from the act of annotation itself. If we want to think about timestamps in a more theoretical or conceptual way, I do think there’s a provocation or an invitation to consider the extent to which time is a perspective—and how a timestamp can be off, depending on that perspective. Whether it’s a human perspective, a particular system, or a specific data format, time shifts. It’s not fixed. |

| 00:22:43 |

Mike O’Driscoll |

So I was teaching T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets yesterday, which is, of course, a poem about time—a really deep philosophical meditation on time—that I would argue can only be understood through listening to the poem. And I think that, in some ways, is Eliot’s argument: you cannot comprehend the poem’s bid for revelation or incarnation through critical description or classroom discussion. You can only get where he wants to take you by listening to the poem.

And that’s predicated on those great lines toward the beginning of Burnt Norton:

“If all time is eternally present, all time is unredeemable.

What might have been is an abstraction,

Remaining a perpetual possibility only in a world of speculation.” |

| 00:23:44 |

Mike O’Driscoll |

And Tanya, as you were talking about the transmediation of timestamps—the ways in which they go awry, and the ways in which they are unredeemable, in Eliot’s words—that’s what I was thinking about: that it’s actually an incredibly complex process to mark time. And we delude ourselves into thinking it’s a matter of simplicity. There’s so much going on in the presumptions we make about redeeming time in the space of durational media, and how we might mark and manage something that, as Eliot says, remains a perpetual possibility only in a world of speculation.

This is not only a deep philosophical problem—it’s also a very complex practical one. |

| 00:24:40 |

Jason Camlot |

Going back to the distinction between analog and digital media, I think the idea of having greater control over something unfolding as it’s represented in a medium is key. And I would add photography to this. We could think of chronophotography, for example—Muybridge being one notable case. [Click-whirr] |

| 00:25:00 |

Sarah Freeman |

Eadweard Muybridge was a 19th-century photographer known for using sequential images to capture motion, pioneering early studies of time and movement. [Click-whirr] |

| 00:25:12 |

Jason Camlot |

And then we can think of early cylinder recordings—and especially flat disc recordings—as having timestamps on them, or at least as representing or manifesting a certain kind of timestamping of time. In Muybridge’s case, each image is, in a way, a timestamp in a series of movements. But on a flat disc record, the spaces between tracks could be seen as timestamps, as the album side unfolds. They help you locate something that could also be matched up with time indicators next to a track—though that happens a bit later.

Then, analog tape recorders began to include time counters. Not right away—in the 1930s, they didn’t have them—but eventually, they did, as it became more important to navigate and manipulate the recordings. So, there’s a strong sense of timestamping as a form of power over time, embedded in whatever media format one is engaging with.

And I guess the point I was going to make about digital technologies, as opposed to analog ones, is that digitized and digital media represent a fuller realization of the timestamp concept in media form. |

| 00:26:35 |

Jason Camlot |

So that is—time in digital media becomes sampled into these micro-temporalities. It’s not fluid in the way we understand analog media to be, because analog is made up of transduced patterns that don’t necessarily have natural breaks within them. But digital media is literally sampled—it’s slices of time. That’s how it’s represented. And so we could say that, as a media form, it lends itself even more to the idea of controlling time in the most infinitesimal ways.

But where I want to go is actually to my last thesis, in relation to what Tanya was saying, which is that timestamps also have the potential to express. That’s the thesis—it’s an ambiguous or cryptic one, and I’m going to unpack it. I think it has something to do with what Tanya was pointing out about the subjectivity of timestamps. What I mean by that is the possibility of an aesthetic or a poetics of the timestamp in itself. And I love the idea that timestamps, when disconnected from their annotations or from their historical or temporal events, can go awry in a variety of ways.

They are primarily mechanisms of precise control over time—for a variety of purposes, to make arguments, to serve different ends. But the example I have in mind is actually a chapter in Jordan Abel’s book Injun. There are a couple of sections where he offers a timestamped transcript from a lecture he gave at the TransCanada conference. And if you read that text as a poem, I think what he’s performing there is exactly what Tanya was talking about—he’s really attempting, in this piece of writing (which consists of a lot of timestamps), to explore that poetics.

I’ve actually read it out loud, and when I quote from it, a long section might be something like: 15:38:53–15:38:54, right? That’s just the passage of a second. But it carries so much weight in how it’s presented. |

| 00:28:56 |

Jason Camlot |

And it just goes on and on—you can literally read that for half a page. But he’s using timestamps in relation to the text, which is also timestamped, but without the same precision. He’s using them to communicate either what’s not being said, or what’s being felt in the interim as he’s reading. He gives a sense of using the timestamp to capture the affect in the room and in the speaker, as that speech unfolds in time.

And the timestamps, as they appear on that page, I would argue, represent a kind of poetics of the timestamp—one that aims to show how time is always subjectively relative. It depends a great deal on how one is experiencing a moment, a second, or whatever unit of time it may be. |

| 00:29:48 |

Jason Camlot |

I think it’s very important, as a sort of initial ethos or way of thinking going into timestamping, to remember that these are determinations. It’s a kind of determinate technique that we’re attempting to use to control time in certain ways. But the poetics—or aesthetic—of the timestamp, as I’m finding it in Jordan Abel’s work, reminds us of something very important. And that’s what Tanya opened with in this segment: the idea that timestamps can be off, and they can be off even when they’re on, in some ways. I guess that’s my point—yeah. |

| 00:30:30 |

Mike O’Driscoll |

Michael, you started this part of our conversation by asking what it was that got us to think a little more critically and carefully about the act of timestamping. And for me, that was very much part of it—the recognition that this was a constructed way of framing, accessing, and receiving durational media and its contents. That in the act of timestamping, as well as in the act of annotation, there is a whole series of historically, ideologically, and culturally bound presuppositions that we bring to that activity.

And that is where the expressivity of the timestamp might lie: in the fact that we carry certain values and meanings into the production of timestamps and annotations. Those values and meanings shape the circulation and reception of the objects we subject to those practices. |

| 00:31:31 |

Jason Camlot |

I have a question for Tanya, actually—and it comes out of the project we’re working on right now, which involves attempting to crowdsource timestamps from people watching a video. It’s a great example of the unhinged timestamp, because we’re trying to bring in timestamps from Zoom and then figure out how to upload them and match them to the AV content.

What I’ve realized as we go through this project is that so much of our work focuses on making sure that the comments—the annotations—are timestamped, that they’re actually linked up to the AV, right?

I’d love to hear, or for all of us maybe to reflect on: what’s the difference in value between a timestamped annotation (which we almost use as one word sometimes) and just an annotation? Like, what if we didn’t timestamp any of our annotations for that event, and we just had this running text? The reader—or the listener—would then have to figure out what’s referring to what. You know? |

| 00:32:34 |

Tanya Clement |

Yeah, no, I think—I mean, if you’re going to do that, then why even do them sequentially? Because I think even the act of having those annotations, the way you described it, gave me a visual of positioning them next to each other—almost like people are listening and looking at them side by side. But that’s also a form of timestamping, right? It’s not as precise, per se, but I think it’s a kind of conceptual timestamping that operates with broader parameters around time.

For example, I was timestamping an interview the other day—mostly just doing transcripts—but I had a range for a particular moment. |

| 00:33:25 |

Tanya Clement |

And it was interesting to me because I kept having to correct myself. I would say, Oh, this is wrong because the timestamp isn’t exactly right. But then I had to remember, as I was listening and then looking over at the timestamp, that I had used a range. So in fact, what the person was saying wasn’t outside the range—it wasn’t at the start time or the end time—it was somewhere in the middle.

But I kept having to remind myself: Oh, it’s not that exact number. The number kept making me think it had to be very precise, when in fact, it could be anywhere within that space. I’m always reminded of Gertrude Stein, right? As human beings, when we’re reading things or trying to understand them, we tend to put them into structures—and we rely on those structures to make sense of what’s happening. [Click-whirr] |

| 00:34:20 |

Sarah Freeman |

Here, Tanya introduces Gertrude Stein, a modernist writer who challenged linear narratives through her use of repetition. Tanya’s evocation of Stein invites us to consider how we impose order on information. Perhaps our uncritical encounters with timestamping reflect a broader tendency: our uncritical reliance on the formal structures of language itself. |

| 00:34:46 |

Tanya Clement |

So I do think that just the simple act of placing notes—again, in my mind, it’s spatial—next to the screen where you see the video means that people are going to tend to read them sequentially, unless you intentionally mix it up. And if you tell them it’s mixed up, then that becomes a whole different experience. But if you don’t tell them it’s mixed up, they might feel confused—and I don’t know if that’s the intention.

So I think one’s intention, if you’re being inexact with timestamping, can be generative, but it can also be confusing. Because when people see timestamps, they tend to assume: this is what’s happening at that exact moment. Or if they see something in sequential order, they assume: this is what’s being talked about first, then this, then the next thing. So you’re still imposing a time-based order, I think. |

| 00:35:57 |

Michael McKenzie |

Yeah, that’s actually so great—it leads me right into the next question, which has to do with the idea of the audio object as a black box. Someone approaching it without something like timestamps won’t necessarily know what’s inside.

My question is about what timestamping does in this context: on one hand, it provides accessibility—it allows you to directly find what you need. But at the same time, some artists or performers might want to preserve a certain sense of enigma or opacity in their work. So timestamping can also risk disrupting that intentional ambiguity.

What I’d like to do now is briefly check out a clip from Jackson Mac Low. I’ll share my screen so we can listen to it together—it’s one of the pieces we’ve timestamped. I’ll share my question with you right after we take a look. [Click-whirr]

Warning: you might want to turn your volume down a little bit. [Click-whirr] |

| 00:37:04 |

Jackson Mac Low – Audio Clip |

[Overlapping, distorted voices]

“…About—honestly, that… Alison Knowles, Carol… Dickens’ farm… Rose Jackson, Scott… take… Gotti? Haha… there’s something… dark—God? Song? Sing? Maybe that. Slide… please… I—I gotta eat… thank God now… guaranteed… body spa? Please…”

Note: This segment contains heavily distorted and overlapping voices. The transcript reflects best approximations. |

| 00:38:30 |

Michael McKenzie |

OK, so that was a clip from Jackson Mac Low’s Fifth Gatha, and I’ve got a few questions. What do timestamps do on a practical level for people using the audio in your practice? And what do you want to avoid with your timestamps in a recording like Mac Low’s, or something else you’ve encountered?

What matters from a practical and theoretical perspective when you encounter a difficult piece like this? And specifically, what I mean by that is: when a piece appears to want to remain enigmatic or appear opaque—not necessarily easy to interpret—what happens when we include, inside our timestamps, descriptive words like inaudible or unintelligible? What does that do? How might that affect a reader or listener when the thing they’re listening to might have the express purpose of being noise, or of being inaudible on purpose?

And so, have you thought about the intersection of those things? And also, more generally, have you run into difficult pieces like this that have really made you think about your practice? |

| 00:39:49 |

Jason Camlot |

Since this came from the Sir George Williams series, and I was there when this first transcription happened—this timestamp mentioned—I could give a little bit of background. And I think it’s a fascinating example for thinking about timestamping in the way we’ve been discussing it.

First of all, how is this timestamped and annotated on the site where it appears? Essentially, there’s a timestamp before the performance of the Fifth Gatha, where Mac Low explains what they’re about to do. The transcript for that explanation is actually connected to a timestamp—so that’s at 01:06:11, where he says something like, I’ll do a piece called Fifth Gatha, and then he goes on to explain what’s about to happen.

Then you have an annotation at 01:09:35, and it just says performs Fifth Gatha, right? And there’s nothing else there. But I’m looking at this, and I’m actually quite grateful that there are no annotations for the piece itself. |

| 00:40:54 |

Jason Camlot |

The reason we didn’t include annotations to describe what was happening in the piece is that we had an approach for all the annotations: not to transcribe any of the poems themselves, so to speak—because we didn’t have the rights to them. Although that probably wouldn’t have applied in quite the same way to this particular work.

So, following that logic: at 01:09:35 it says performs Fifth Gatha, and then at 01:26:20 he starts talking again. So all we have is the time span during which that piece unfolded, and that’s the only annotation that exists in relation to that timestamp. |

| 00:41:34 |

Jason Camlot |

So there’s not much there, other than the fact that a certain amount of time took place—or unfolded—when this particular piece was performed. The other thing I’d mention is that we approached it with the sense that transcribing it wouldn’t necessarily have been advisable anyway. Instead, we did a lot of contextual research around the event to try to understand what it was we were hearing.

And that, probably, would be more interesting to actually include—because we learned quite a bit from conducting an oral history with two of the technicians who were there assisting Mac Low. They told us about the setup in the room: there were five reel-to-reel tape recorders that had been pieced together. I even saw the tech list that Mac Low had submitted, and that made all the technicians laugh when they were together in the room. |

| 00:42:21 |

Jason Camlot |

It was like, there’s no way we’re getting him this stuff, you know? But they cobbled together a bunch of machines. This piece was performed in other places at other times, and he would play those performances while the one happening in the room was also being performed—and recorded by another machine, right?

So, essentially, to timestamp this would be extremely complex, because it’s an event unfolding in multiple places at the same time—in New York, and wherever else he was—as well as in the present moment. And then that tape would be brought to a future performance, and so on.

So, in this case, I think some explanation of the context of what we’re listening to would probably be even more useful than attempting a transcriptive annotation. |

| 00:43:15 |

Mike O’Driscoll |

The gaffes are really important for Jackson, as I understand it, in part because they’re one of his many challenges to the centered, stable, egoic presence of the author in the production of the work. In particular, with these polyphonic pieces, he’s challenging notions of a monologic, expressive lyric subject and disrupting our presumptions about the authority that rests with that voice. And the gaffes do really interesting work in that regard.

But the other thing they do—and you could say this about a lot of Jackson’s work—is tied to its recursive nature. He’s working with computer technologies and other algorithmic systems to produce his work in the first place, and he’s drawing from discursive corpora of other authors. Gertrude Stein came up earlier in our conversation, and the Stein poems would be a really good example of that—but there are many others as well.

One of the things he’s doing is also challenging our notions of time. The linearity of the performance piece, its monologic subjectivity, and its stability—these are all things that he’s disrupting in a piece like The Gathas. And these, in turn, are the very presuppositions we often bring to the practice of timestamping.

In other words, in a very fundamental way, Jackson’s art forms challenge the basic suppositions we hold when we think about duration, performance, event, and subject. All of those things come under scrutiny—and all of them are disrupted in one way or another by his work. That’s why the limit case you shared with us is such a wonderful way to get us to rethink the fundamental ideas we bring to the activity of marking durational media. |

| 00:45:35 |

Michael McKenzie |

Yeah, that’s so great. OK, the next question has to do—and this might be interesting to you—with constrained vocabularies or standardized vocabularies that are used in style guides. What happens when the only option, for example, when someone is reading or performing something, is to choose the word perform—which is the case here at UVA?

What goes into deciding on a standardized vocabulary or a reduced set of words that we’ll use when annotating or timestamping? What’s the thought process behind determining that perform is going to be the word we use, and not read? |

| 00:46:28 |

Tanya Clement |

Yeah, I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about that, because I mean—it’s really the most difficult part. So for our project, we allow people to index the annotations, and that includes a tag. That tag allows you to group your annotations in particular ways, which then lets you access them according to those groupings later.

So, let’s say your annotations are transcripts, and you want to add speaker names as tags so you can see everywhere that a particular person has spoken across a project—because all of their annotations have been tagged with their name. The same could be true if, say, you were working within a particular theoretical perspective, and you had terms that might be adopted in the context of that theoretical positioning—you might want to tag a transcript based on those.

I guess the short answer is: it depends on your theoretical perspective. It depends on what it is you’re trying to pull out or identify as significant in a particular recording. You don’t have to do transcripts at all, really. A lot of people tend to do them because they create better access for listeners or users. But I think the larger point is: it depends. It depends on what you’re trying to mark as significant. |

| 00:48:08 |

Jason Camlot |

To build on what Tanya said—why reads versus performs—that’s an interesting question, right? The short answer is: it allows you to do things with larger amounts of data that you couldn’t do otherwise.

So, the very first thing we did with SpokenWeb in the first year—the first task force we struck—was our Metadata Task Force. That was in anticipation of having hundreds of hours of audio that we were planning to describe. We were imagining doing things with that material which, without some kind of controlled vocabulary and grammar for our schema, would have been much more difficult—especially if we wanted the recordings to teach us things about each other when placed in relation to one another.

When I say it allows us to do things we couldn’t do otherwise, I mean we were looking at other existing schemas—their vocabularies and grammars—to ensure that, if we came across other collections that already had some metadata, we’d be able to bring it in, or ingest their metadata, more easily than if we didn’t have a shared structure.

So we wanted to make sure our terms were interoperable with other standardized languages or grammars. But we also wanted, as much as possible, to ensure that we were tagging, annotating, and describing individual recordings in a way that categorized them meaningfully. |

| 00:49:40 |

Jason Camlot |

So that if we then faceted our larger dataset by a search term—like, say, poetry reading or radio broadcast—it would bring up all of the recordings, or as many as are appropriate to bring up under that category. It allows us to actually search a larger corpus of audio more effectively, and also to make connections across recordings in ways we might not have even thought of yet.

For example, if we’re interested in the distinction between performing versus reading, perhaps that becomes a useful search term for locating more experimental kinds of performance within the contents fields themselves—which one could do, if one wanted to, because that vocabulary was adhered to.

So the vocabularies can be useful, but they are all forms of abstraction—necessary forms of abstraction if you want to do this kind of more distant searching or reading of the contents. They’re useful in their own ways, but abstractions also do violence to the particulars of the events themselves. They’re not always accurate, or fully capable of capturing what’s actually unfolding—but they’re useful up to a point, depending on the goals one might have when working with these materials as data.

And that’s the other thing that’s really happening in a lot of this work: we’re converting qualitative humanities content—speech, performance, sound of various kinds—into different forms of data, by using these controlled vocabularies. |

| 00:51:21 |

Mike O’Driscoll |

One of the things I really love about these kinds of questions—and this is something that has become more and more apparent over time in working with archives of audio media in the context of SpokenWeb—is that every one of these practical questions actually has an incredibly rich intellectual, theoretical, and scholarly background. And that’s quite an amazing thing.

So I would say, for example, that the difference between performance and reading—if we designate the activity of a particular author on stage who’s been recorded as reading a work—for me, it connotes the idea that the literary audio performance is secondary to a print version of the text. That you are reading—that it’s derivative, right? That it follows from something else.

Whereas the notion of performance, for me, carries the weight of the performative. In other words, it’s a constitutive medium of its own. A performance produces a text that is not secondary or derivative to the print version—it’s its own beast.

And so, the language that we use to describe the work we’re doing in this regard can carry some pretty heavy connotations. But that only comes under scrutiny—only becomes a matter of discussion—when we sit down and deliberate: how do we describe these things? And what values does it carry to do it one way or another?

That’s the part that’s most exciting for me. Getting to the practicality of it—being able to produce constrained vocabularies to increase searchability, interoperability between different systems, and all of the things that go along with that—is really crucial.

[Upbeat instrumental music starts playing] But the fun part is the conversation that gets you there. |

| 00:53:41 |

Sarah Freeman |

Timestamping doesn’t happen in a bubble. During our roundtable, timestamping took us through history—as we discussed, for instance, Gertrude Stein, medieval annals, Hayden White, Victorian periodicals, and Stonehenge. We reflected on the intricacies of the controlled vocabulary used in timestamping and its broader applications, from EKG machines to SETI protocols that extend far beyond literature.

We also explored what it means to timestamp a recording that resists singular meaning—such as Jackson Mac Low’s Fifth Gatha. Most of all, we learned that timestamping is far from a settled field. There is no objective or universal timestamp. Each one results from a series of subjective, contingent, and political decisions made by the time stamper.

Timestamping is an invitation to intervene, to interpret, and—most of all—to create. |

| 00:54:49 |

Sarah Freeman |

Thank you to our roundtable participants—Jason Camlot, Tanya Clement, and Michael O’Driscoll—for their insightful contributions to our discussion.

Further thanks to Michael O’Driscoll, Sean Lowe, and the SpokenWeb Podcast production team for their support in creating this episode.

Technical support was provided by the Digital Scholarship Centre at the University of Alberta.

This podcast was produced by Natasha D’Amours, Michael MacKenzie, Xuege Wu, and me, Sarah Freeman. |

| 00:55:41 |

Hannah McGregor |

You’ve been listening to the SpokenWeb Podcast. The SpokenWeb Podcast is a monthly podcast produced by the SpokenWeb team as part of distributing the audio collected from — and created using — Canadian literary archival recordings found at universities across Canada.

This month’s episode was produced by Natasha D’Amours, Michael McKenzie, Sarah Freeman, and Xuege Wu, and features the voices and smart ideas of Jason Camlot, Tanya Clement, and Mike O’Driscoll.

The SpokenWeb Podcast Team includes supervising producer Maia Harris, sound designer TJ McPherson, transcriber Yara Ajeeb, and co-hosts Katherine McLeod and me, Hannah McGregor.

To find out more about SpokenWeb, visit spokenweb.ca and subscribe to the SpokenWeb Podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you like to listen. If you love us, let us know — rate us and leave a comment on Apple Podcasts, or say hi on our social media.

Plus, check out our socials for info on upcoming listening parties and more. For now, thanks for listening. |