| 0:00 |

SpokenWeb Podcast Theme Music: |

[Instrumental Overlapped with Feminine Voice Begins] Can you hear me? I don’t know how much projection to do here.

|

| 00:18 |

Hannah McGregor: |

What does literature sound like? What stories will we hear if we listen to the archive? Welcome to the SpokenWeb Podcast, stories about how literature sounds. [End Theme Music]

|

| 00:35 |

Hannah McGregor: |

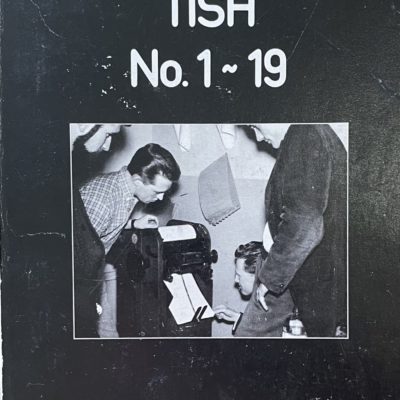

My name is Hannah McGregor, and each month I’ll be bringing you different stories of Canadian literary history and our contemporary responses to it created by scholars, poets, students, and artists from across Canada. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, one of the most cohesive writing movements in Canadian literary history began at UBC Vancouver—the TISH poetry movement. The voices of many TISH community members have been archived and cared for within the SoundBox collection at UBC Okanagan’s AMP Lab as part of the SpokenWeb Project. Today, UBCO Masters student Craig Carpenter brings us on an immersive and personal sonic journey into the life and poetry of one TISH: poet Robert Hogg. Craig was a student of Dr. Hogg’s, and in this episode, he weaves archival recordings together with original interviews with Bob, taking listeners on a poetic journey. The episode takes us back and forth in time—into the sonic spaces of poetry readings, the laughter of present day conversations, and worlds of memory and reflection. This is an audio story about Robert Hogg the professor, Bobby the poet, the TISH community, the power of Canadian poetry, and the moving emotion of mentorship and connection across decades of shared inspiration. Here is Craig Carpenter with Episode 10 of the SpokenWeb Podcast: Robert Hogg and the Widening Circle of Return.

|

| 02:11 |

Original Music Score by Chelsea Edwardson: |

[Begin Music Gentle Instrumental] [Faint voice and car sounds in background] Mountain Path Farms…Hogg.

|

| 02:31 |

Craig Carpenter: |

It’s August of 2019. I’m on my way to visit my old professor at his farm on the outskirts of Ottawa. As I approach, I notice one of the “Gs” of his last name has fallen off the sign at the foot of the long drive towards Mountain Path Farm. This is where Robert Hogg raised his family, ran his flour mill, and studied and crafted his poetry since the 1970s. It’s been a quarter of a century since I knew Bob as my professor of modern Canadian poetry at Carleton University.

|

| 03:10 |

Sound Effects Mixed with Original Music Score by Chelsea Edwardson:

|

[Gentle Instrumental Music Continues] [Sound of car key turning off the ignition and car door opening] |

| 03:24 |

Craig Carpenter: |

When Bob greets me at the door, I reflexively call him Professor Hogg. He is just as I remember, except a little more rounded and perhaps a bit more jovial in nature. As Bob offers a quick tour of the old farmhouse, our feet creek the fat wooden plank flooring, and I wonder—who else has trod these floors? What stories could they tell? [End Gentle Instrumental Music] [Sound Effect: Whirring sounds of tape rise] [Faster Instrumental Music Begins]

|

| 04:01 |

Craig Carpenter: |

I have decided to return to school to work with Dr. Karis Shearer on the SpokenWeb Project. A box of tapes donated by my former professor awaits digitization. [Sound Effect: Whirring sounds of tape end] The box contains recordings of his own poetry community from the 1960s at UBC’s Vancouver campus.

|

| 04:24 |

Audio Recording, Short clips of Warren Tallman, Fred Wah, Daphne Marlatt, and George Bowering from PennSound Archives:

|

[Instrumental Music Continues] The microphone may seem like a lot of rigmarole, but actually…it’s necessary. [Faint voice] This isn’t working? [echoing inaudible voices] Poem. Poem. [Stammering voice] Did that introduction – does that come off my twenty minutes? |

| 04:46 |

Craig Carpenter: |

[Gentle Instrumental Music Continues] The voices of his former professor Warren Tallman and his peers, Frank Davey, Daphne Marlatt, Gladys Hindmarch, Fred Wah, and George Bowering are not only being preserved through digitization, but remediated and re-presented through new forms, such as podcasts like this one.

|

| 05:10 |

Original Music Score by Chelsea Edwardson:

|

[Gentle Instrumental Music Continues] [Audio recording, Sounds of door latch opening] |

| 05:17 |

Craig Carpenter: |

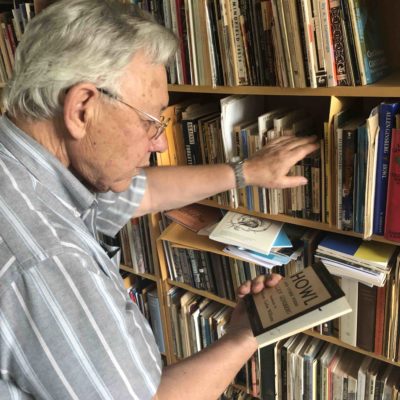

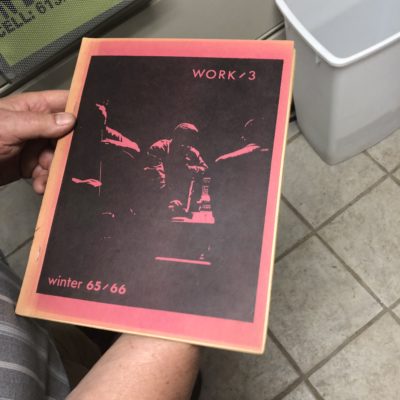

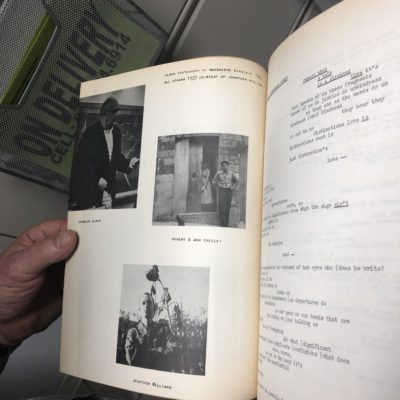

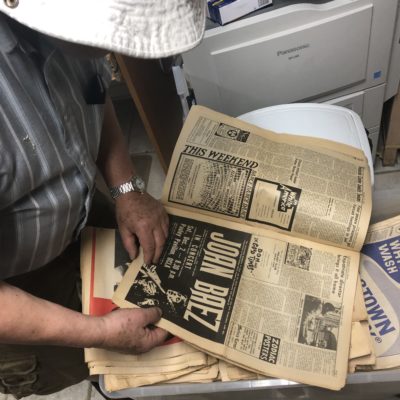

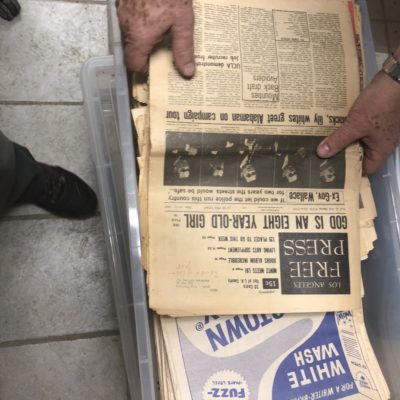

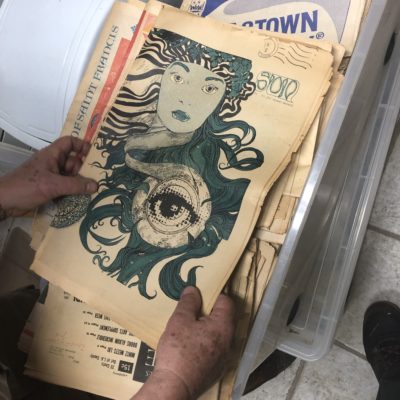

After the tour of the farm house, Bob asked me to give him a hand moving a few things in the barn. The barn is oddly clean for a barn, I think. In fact, there is an astonishing order to everything at Hogg farm. Even the out-of-order tractors appear to be meticulously cared for. Bob shows me the remnants of his old grain mill. He somewhat softly recounts its last days of operation. And then his demeanor shifts. There’s a sudden bounce in his step as I follow him up a set of stairs to what used to be a hayloft. We take a bin filled with periodicals down to an old office. [Recording of voices rises in the background] The former office is jammed with books, magazines, and bins of papers. There’s scarcely room to step as we enter. This is what Bob refers to as the overflow of his poetry collection. [Gentle Instrumental Music Continues]

|

| 06:21 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Robert Hogg:

|

[Inaudible] …this says sun, S-U-N… [Sounds of rustling papers.] Georgia Straight…one of my poems was in there too. Anyways, somebody somewhere along the line will want to go through all this stuff, I knew most of the Beat poets… |

| 06:31 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Craig Carpenter:

|

You did. |

| 06:33 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Robert Hogg:

|

…The only really important Beat poet I never met with Jack Kerouac…[Recording continues and fades. Gentle Instrumental Music Continues] |

| 06:34 |

Craig Carpenter: |

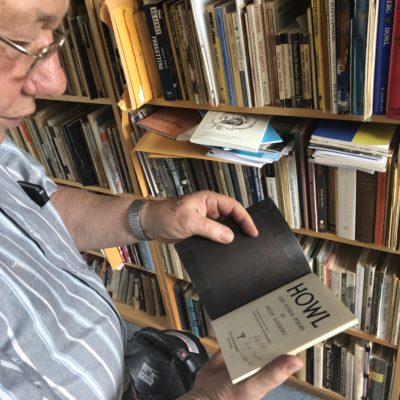

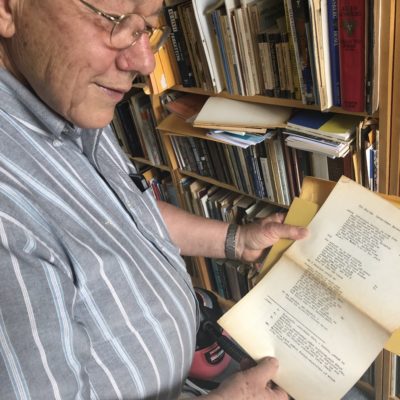

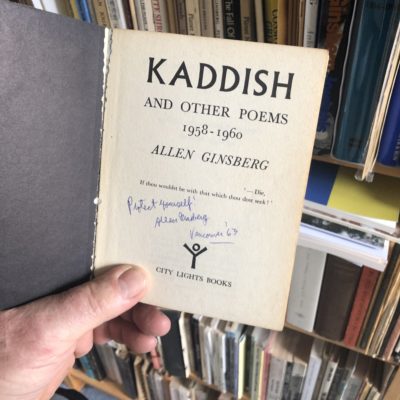

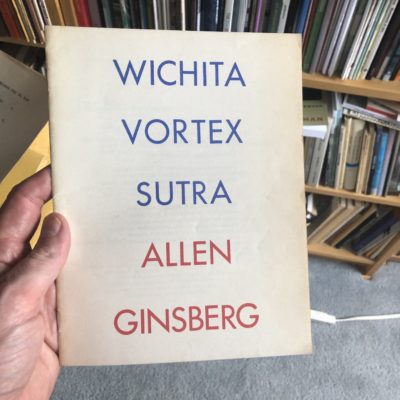

It would be easy to spend hours sifting through the old journals. But finally, we head back to the house and up the narrow wooden stairs to Bob’s writing room. [Instrumental Music Tempo Increases] The slanted ceiling meets an entire wall of books stacked with first edition Ginsbergs and Kerouacs. Knowing this is where Bob crafts his poems, the attic feels like a cathedral of sorts. Bob positions himself behind his desk and turns on his computer. He is keen to record himself reciting his work.

|

| 07:19 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Robert Hogg:

|

Alright. |

| 07:20 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Craig Carpenter:

|

And let me just get this in a better position, and…[inaudible]…I’ll just monitor that while you read…Just do a test first. |

| 07:31 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Robert Hogg:

|

Yeah…Okay, so I’m going to read a poem called “Amber Alert”, and I’ll just read the first few lines and we’ll test it out. [Reading poem] It was a day like any/ other you know / the kind the poet/ wrote about /people/ going about their business. [Ends Poem] |

| 07:44 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Craig Carpenter:

|

That’s good. Yeah, I think we’ve got that good so… [We hear a click as Craig presses play on the recording and Bob’s voice appears again] “a day like any/other you know / the kind the poet/ wrote about /people/ going about their business.” |

| 07:56 |

Craig Carpenter: |

[Gentle Instrumental Music Continues] Bob reads a few newer poems. I’m reminded of William Carlos Williams by some of Bob’s poetry, and we begin to talk about the poetics of Williams and Ezra Pound who were both major influences on the TISH and the American Black Mountain poets. We discuss Williams’ statement: “No ideas but in things.”

|

| 08:17 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Robert Hogg: |

You do need to remember that one of the problems with modern verse, when you drop all the trappings that were typical of traditional writing in the form and structure—like a sonnet, for example, with its rhyme scheme and everything—you are left with a fairly naked body of words, right? And something in those words has to keep that poem cohering for people…it has to keep jumping at you in some way. And of course, between Pound’s insistence on the image and Williams’ more direct insistence on the Thing, which is also of course the image — you know, that helps to bring that idea of the vividness of experience into focus in the writing of poetry. [End Gentle Instrumental Music]

|

| 09:02 |

Audio Recording, PennSound recording of William Carlos Williams reading “The Red Wheelbarrow”:

|

The red wheelbarrow // so much depends / upon// a red wheel / barrow // glazed with rain / water // beside the white / chickens |

| 09:11 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Robert Hogg: |

Things trigger, right? They really do. They are they—I think that could be, that could be quite, quite exciting at times. And I guess, sometimes it leads to something quite profound and other times it just leads to something, you know, a little bit more expressive or it widens the perception or whatever it does, or deepens it maybe. Hand me those scissors. You can hand them to yourself. [Craig laughs] This poem is called “A Miller’s Tale.” [Reading poem] These tailors sheers / that long before I was born / cut yards of fabric my English grandfather sewed into clothes / for Finchley’s finest / somehow passed onto my father / settled in Canada after the Great War / never used them for anything so far as I can tell / except to leave them to me who gave them a second life / when I opened the flour mill / mountain township 1983/found them rusting slightly / ideal for trimming paper flower bags / 25 to 10 kg / and after stitching cut the thread old job once again / as fate would have it/lying now on the carpet of my study floor / tucked under the tredel of mom’s old Singer sewing machine/sent from Langley decades back / the plywood crate reworked to become the grain hopper of both my 30 inch stone mill / it must be 30 years before it all went still. [Poem ends] And that’s the sewing machine over there, and they typically lay underneath the treadle. I have been using them lately so that’s why they’re in my drawer. Yeah. Yeah. [Sound effect of shearers clipping echoing.] [Gentle Instrumental Music Begins]

|

| 10:49 |

Craig Carpenter: |

It’s 1959 in the sleepy town of Abbotsford, British Columbia. Among the carousels of paperbacks at Bennion’s Pharmacy the teenage Bobby Hogg is stumbling across Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. The only poetry Bobby has heard spoken aloud up to this point is the Victorian verse his father recited to him as a child. He loved listening to his Dad recite poems. But like so many of his generation, it’s On the Road that opens up a new way of hearing words and seeing the world. It isn’t long before his high school friend Frank Davey, who has skipped a couple of grades and gone off to UBC ahead of him, is bringing Bobby the City Lights Pocket Poets Series books. Bobby devours the little books filled with free verse. Among his favourites: Ginsberg’s Howl, Gasoline by Gregory Corso and the selected poems of Robert Duncan.

|

| 11:47 |

Sound Effects Mixed with Original Music Score by Chelsea Edwardson:

|

[Gentle Instrumental Music Continues] [Low rumble of a car driving mixes with the music] |

| 11:56 |

Craig Carpenter: |

At the end of December 1959, Frank pulls into Bobby’s driveway in Langley where his family had just moved. He’s driving his ‘47 Ford coupe. He orders Bobby to get in. [Sound of car door shutting] Frank’s professor Warren Tallman and his wife Ellen have invited Robert Duncan to Vancouver to read. Duncan is here. In person. In the Tallmans’ basement. Tonight. Bobby didn’t have a choice.

|

| 12:26 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Robert Hogg: |

I said, “well, I’m busy,” he said that doesn’t matter how busy you are, you’ve gotta come. And it was like, I mean, if he put a shotgun to me as it were. And says, if you don’t come to this you’re blowing your whole life—which was, totally would have been true. So, I can’t remember now whether I jumped in his car with him. We both had—he had a ‘47 Ford coupe and I had a ‘48 Ford coupe. Real classic cars in our time. And so, I either went with him, which I think I did, and then he must have had to bring me back again the next day or something. In any case he did. We went in together and I heard Robert Duncan read his poetry in Warren’s basement. That was absolutely the quintessential moment in my entire life in terms of poetry, because I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. I was really hearing poetry from a distinguished person that I had never been able to hear before. I mean I’d read famous poets but I’d never heard one read. So I went from being just sort of genuinely interested in poetry to being converted, I guess you could say, by this experience. And I think I felt from that moment on I would probably have to write poetry as a means to survive, right. In my spiritual side, right. And it’s been true for me ever since. And he read the poems that were then subsequently published in The Opening of the Field including that famous poem, “Often I am Permitted to Return to a Meadow,” which is the poem I think he started off the reading with. [End Gentle Instrumental Music]

|

| 13:40 |

Audio Recording, PennSound recording of Robert Duncan reading “Often I am Permitted to Return to a Meadow”: |

Often I am permitted to return to a meadow // as if it were a scene made up by the mind, / that is not mine, but is a made place, // that is mine, it is so near to the heart, / an eternal pasture folded in all thought / so that there is a hall therein // that is a made place, created by light // wherefrom the shadows that are forms fall. // Wherefrom fall all architectures I am / I say are likenesses of the First Beloved / whose flowers are flames lit to the Lady. // She it is Queen Under The Hill / whose hosts are a disturbance of words within words / that is a field folded. // It is only a dream of the grass blowing / east against the source of the sun / in an hour before the sun’s going down // whose secret we see in a children’s game / of ring a round of roses told. // Often I am permitted to return to a meadow / as if it were a given property of the mind / that certain bounds hold against chaos, // that is a place of first permission, / everlasting omen of what is.

|

| 14:45 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Craig Carpenter:

|

What was the effect of actually hearing him? |

| 14:48 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Robert Hogg: |

Well, the effect was incredible, because we hadn’t—The Opening of the Field was not yet in print. It came out that year actually in 1960. But, well, the next year—it was ‘59 when I actually heard him. But still, it was almost 1960, it was like the end of December, 1959. And that book came out with Grove Press just a few months later. But he was reading from manuscripts still, right? So the poems that were in The Selected Poems were not like the poems in The Opening of the Field. He broke new ground there. It was a lot more accessible. It was a lot—to me it was a lot more poetry that somehow spoke about poetry. I mean that very poem “Often I am Permitted to Return to a Meadow”—that meadow immediately becomes a page, it becomes the subject of poetry itself. [recites part of the poem] as if it were a scene made up by the mind, / that is not mine, that is a made place // that is mine, it is so near to the heart, / an eternal pasture folded in all thought. [ends recitation] I mean, all those things are statements about writing, right? And then he says, “that is mine, it is so near to the heart.” Okay, [laughs] I’m hearing that, and I’d never heard anybody talk about the act of writing. I mean, I think I intuited right away that this was a poem about writing not about a meadow or some children playing a children’s game. It really was all about the process of writing. That’s what I think I heard — something new about writing, which is often about writing. It’s surprising how much of modern poetry [Begin Gentle Instrumental Music] and maybe all poetry has been to some degree about writing.

|

| 16:21 |

Craig Carpenter: |

Bob tells me this now mythic Duncan reading set off a chain of events that included the evolution of TISH. We now know, from the work on hidden labour that SpokenWeb researchers Deanna Fong and Karis Shearer have done, that it was Warren Tallman’s wife, Ellen, who knew Duncan personally, and not only arranged for him to come read, but also helped select which poems he would read. Bob explains to me what it was about this reading that changed his relationship to poetry.

|

| 16:52 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Robert Hogg: |

What that reading that he gave in Warren’s basement did for me, I think, that nobody else had done before [End Gentle Instrumental Music] and probably very few people have done since, was that it gave me a sense of the physicality of language as it was being spoken. Not only in the gestures that he was making. The body—the way he embodied, he seemed to embody poetry for god’s sake, he was like a walking poem. He was very much—he was a showman and he was very much involved in being like a shaman, shamanistically, you know demonstrating with his body what the poem was about. Robin Blaser was a bit like that too. I don’t mean to say in the cheapest sense of showmanship, there was a bit of showmanship in it too, let’s face it. But it really had to do with wanting to show physically what was going on in the physical nature of the poem. I had been taught about poetry that had things going on in it. Like you could scan a poem and you could say, yeah it’s got iambic pentameter, it’s got anapestic, whatever, four beats to a line, or whatever. But nobody made me hear a poem, nobody made me think of the poem as a physical gesture that was being spoken aloud. And that was the thing that I really got from Duncan’s reading. I heard poetry being read aloud as though this was what its real articulation was, not on the page but in the air. And in his body and my body because we’re both in the same room together and I’m hearing and feeling it, the way you do music. It’s like trying to stand still when some really incredible rock band is playing right in front of you. It’s pretty hard [laughs], sometimes you just gotta move with it. You just want to say, oh my god, I really feel, I just want to dance. The dance that was part and parcel of Duncan’s poetic sensibility and his gestures as a writer I think really hit home for me. [Begin Gentle Instrumental Music]

|

| 18:49 |

Craig Carpenter: |

Declared “the Wonder Merchants” by Warren Tallman in his essay of the same title, the group of poets who created TISH magazine were all students of Tallman’s at UBC in the late 1950s and early 1960s. They are known for having been heavily influenced by the American Black Mountain poets, including Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, and Robert Duncan. Critic C.H. Gervais calls TISH one of the most cohesive writing movements in Canadian literary history. My old professor, another Robert, was a “TISHITE” or a member of TISH himself and considered part of the second wave of the movement. After Bob hears Duncan read, the following fall, he follows Frank to UBC. Like his friends Frank and George Bowering who precede him, and other second-wave TISH editors like Daphne Marlatt and Gladys Hindmarch, Bob takes poetry classes with Warren Tallman.

|

| 19:51 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Robert Hogg: |

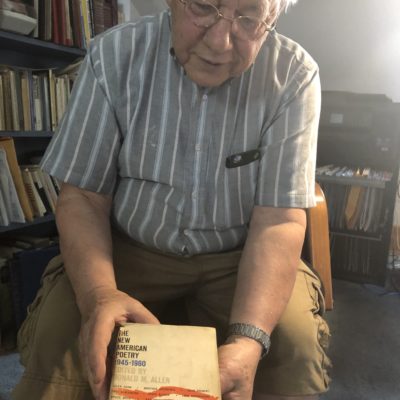

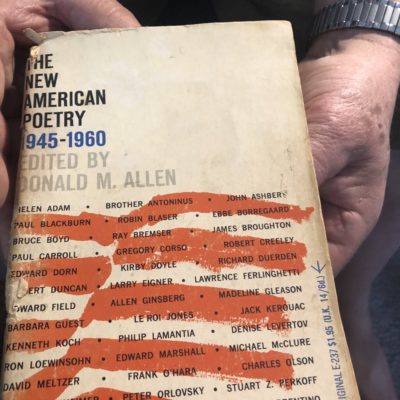

[Gentle Instrumental Music Continues] The most important thing, in some ways, besides Duncan’s reading in Vancouver at that time, was the emergence of the New American Poetry Anthology by Donald Allen, right. Not only did it have poetry by all these people in it—

|

| 20:02 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Craig Carpenter:

|

That was the book I think we studied. |

| 20:04 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Robert Hogg:

|

Yeah, yeah. In my class. Yeah, no doubt. I still have copies. I even have my original here. This is my old original copy. If this was on video it would be exciting. [Gentle Instrumental Music and Audio Recording continue under narration] |

| 20:14 |

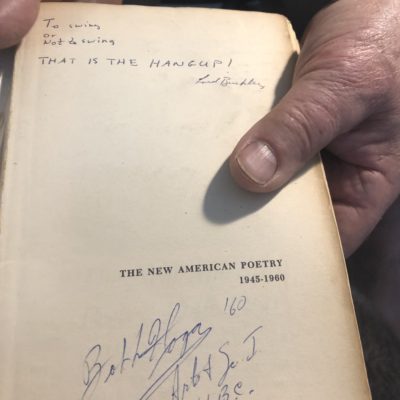

Craig Carpenter: |

As his cat jumps onto his desk, Bob pulls a well-thumbed and marked-up copy of the New American Poetry Anthology from his bookshelf.

|

| 20:21 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Multiple Speakers:

|

I’ll take a photo of it. This is a first edition probably. It is utterly falling apart. 1960, see that? Bob Hogg. What’s it say, Arts one at UBC. [Laughter] |

| 20:37 |

Craig Carpenter: |

[Gentle Instrumental Music Continues] Like the old books on Bob’s shelf, there are audio reels from the late 50s and early 60s that are also falling apart. These reels hold living memory in voice. They are the only means we have to hear how poets spoke their poems aloud. And unlike books, these literary analog audio objects are at risk of decaying and disappearing forever [Sound Effect: tape slowing down on reel] if they are not preserved through digitization. [Sound Effect: Sound of click and reels rewinding]

|

| 21:04 |

Craig Carpenter: |

[Begin Faster-Paced Instrumental Music] It’s late Spring of 2019 and Professor Karis Shearer and I are in the AMP Lab at UBC Okanagan. Karis shows me the box of analog reels given to her by her colleague Jody Castricano. Warren Tallman gave Jody the box and told her when the time was right she’d know what to do with them. It’s been over two decades since I’d threaded a reel-to-reel machine. Scrubbing my memory from second year radio journalism class, I manage to loop the brittle 50-plus year old magnetic tape across the playheads and onto the take up reel. [Sound effect: Threading tape and clicking play]

|

| 21:50 |

Audio Recording, PennSound recording of Warren Tallman: |

Flood tide below me, I see you face to face. [Inaudible] of the west…[Recording continues under narration]

|

| 21:57 |

Craig Carpenter: |

Tallman’s voice leaps out of the machine at us. As if magically fast forwarding through time, his rich harmonic tone captures us immediately. [Audio, from recording: …the tires and the usual costumes…] Its magnetic authority and ringing certainty must have been incredibly moving to hear in person as a student.

|

| 22:19 |

Audio Recording, PennSound recording of Warren Tallman:

|

…Are more curious…. |

| 22:21 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Robert Hogg: |

[Recording Ends] [End Faster-Paced Instrumental Music] Well, he was a remarkably beautiful prof. How else to say it? I think he did more to make poetry available to me as a young writer and as a young reader. I think those two words are almost synonymous with each other. I try to tell people today, if you’re not a reader of poetry, you can’t be a writer of poetry. And if you think that reading your friend’s poetry is being a reader of poetry, you’ve got another learning curve coming because there’s so much wonderful poetry that’s been written throughout the ages that we all have to become more immersed in in order to have some sense of what we are trying to do ourselves as writers. And Warren was remarkably eclectic in his appreciation of poetry. Warren had a great capacity for reading poetry and letting every syllable of the poem have its own articulation. And I guess I might’ve said this before, and I’m not sure if it was in talking with you, but one poem he read was “Lapis Lazuli” by Yeates, which just absolutely blew me away. And I can still hear him reading that poem with his slow, deliberative unfolding as the poem progresses so I can’t recite in full, but…[Sound Effect: Click and whirring of tape on a reel] [Begin Gentle Instrumental Music]

|

| 23:49 |

Craig Carpenter: |

It’s the fall of 1995. Ottawa is overflowing with small poetry journals and regular poetry readings. I’m studying poetry with Bob at Carleton. We read Charles Olson and Canadian poet bpNichol. I take over editing the Carleton Arts Review from the infamous Ottawa poet, the lowercase rob mclennan. rob churns out zines, pamphlets, posters, littering the city with free verse. This same year, Bob flies back to Vancouver to revisit the stomping grounds of his old poetry community and give a reading. Among the box of tapes Bob has donated to the Lab, is the 1995 recording of his reading at Black Sheep Books. [Sound Effect: Tape sounds] It is among the first tapes to be digitized from the box Bob donated to the Lab.

|

| 24:49 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg reading “Extreme Positions for bp” at Black Sheep Books in 1995: |

Extreme positions for bp. [Gentle Instrumental Music Ends] The lovely play language is / the lay of the poem / the place made / the dropping or adding of a letter / tension / Love crosses all bodies of water / or of land / violent / Love knows its own bounds but crosses these / willingly / Knows to stay / stray / brings the point of light / right up to the eye. Knows that all event is also a screen / retina / page / where the hand trembles / to leave a mark in / violet space / so great the mind’s demand that a map be drawn / lines be drawn / against chaos / but also break the edge / put an S on things / put S in the world / sing / silent / space / spell / sound / light / words standing / alone / essential / free / The lovely play / love is / a language made / sign / against unknowing. [Sound Effect: Click of a stop button]

|

| 26:17 |

Craig Carpenter: |

[Begin Gentle Instrumental Music] My younger self never thought to ask Professor Hogg much about his own poetry. I had no clue that my professor had not only studied under Charles Olson in the early 60s at SUNY, Buffalo but had written his thesis on Olson’s MAXIMUS POEMS under the guidance of Robert Creeley. As I sit with Bob in August of 2019, I feel so grateful that time’s turned as it has and I find myself meeting him again. I am beginning to get to know Bobby the poet.

|

| 26:48 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Robert Hogg: |

[Gentle Instrumental Music Continues] …general literature course and creative writing. Then in my third year, I could take poetry or whatever. And I actually got the credit for the poetry course by taking the summer conference. So, in a way I was with Bob Creeley and Ginsberg and all the rest of them for that. [End Gentle Instrumental Music] But I knew Bob, and I hung around him to a certain degree, not a huge amount, but was in his presence and heard him read on at least a couple of occasions I’m sure in that year he was in Vancouver. Also, he read from The Island, which just came out. And when he read the prose in The Island when it first came out, and he read almost like a poem.

|

| 27:19 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Craig Carpenter: |

Yeah, a big inspiration to me. Hearing him from these tapes, I have a recording. [Bob: Okay.] I could even play you some of it. What is it…[recites from poem] goddamn big car and drive. [Bob: Oh yeah. Drive he said, yeah.] Yeah, drive he said. But the way that he read it was so different than how I read that. I was sort of whoa. Even the way that—I thought, well, no, there’s a break there.

|

| 27:39 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Robert Hogg: |

That’s right, in that particular poem he really freaked me out too. I never got that poem right until I heard him read it, right? Yeah, exactly. Exactly. Exactly. Yeah. That’s funny, a lot of people misunderstood that poem. [Laughs]

|

| 27:58 |

Audio Recording, PennSound recording of Robert Creeley reading “I Know a Man”: |

This is a poem called “I Know a Man.” As I sd to my / friend, because I am / always talking,–John, I // sd, which was not his / name, the darkness sur- / rounds us, what // can we do against/ it, or else, shall we & / why not, buy a goddamn big car, // drive, he sd, for / christ’s sake, look / out where yr going. [Audience laughter]

|

| 28:17 |

Craig Carpenter: |

[Begin Gentle Instrumental Music] Some critics of TISH say their work was too influenced by the American Black Mountain School. Bob explains to me that it was more their poetics than their poetry that had really attracted TISH members. Bob had met Olson at the 1963 Vancouver poetry conference organized by the Tallmans. In the Fall of ’64, Bob visits Buffalo and attends one of Olson’s lectures. With the support of Olson, the young Bobby is fast-tracked to his PhD at SUNY.

|

| 28:45 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Robert Hogg: |

Yeah, very lucky. And then when I first went there, it was like many of us who were there for Olson were only there for Olson, we were not there for a PhD. [End Gentle Instrumental Music] Fred was there for that, I was there for that. Some of the English poets like John Temple and Andrew Crozier. Many many people that were hanging around Olson were there—‘oh my God this guy’s interesting, this is why I want to be here.’ Some stayed on and did the doctorate with either like, with him or, in my case, on him, later on, under Bob Creeley.

|

| 29:10 |

Craig Carpenter: |

[Begin Gentle Instrumental Music ] The attraction to study with Charles Olson was in large part because of the incredible power of his poetic manifesto: the “Projective Verse.” The dense and poetic prose of the “Projective Verse” essay can be confounding. Olson works with words like a sculptor’s stone, shaping them physically, employing ALL CAPS and indents creatively with a force that opens the ear anew.

|

| 29:37 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Robert Hogg: |

But I mean, I think it really, really was unique. And I’ve said this to so many people, [End Gentle Instrumental Music] when you read something like the projective verse essay, you weren’t just reading Olsen’s ideas, you were reading about his own percussive and projective style. It was the style in which that essay was written that was hammering itself out to you. And like you said earlier, like with the typewriter, the way Olson made use of the typewriter and typeface, which he also talks about in that essay, was extremely important. And so we’re talking about changing the morphology of language itself and the structure of language. And grammar. I was very interested in how the grammar of poetry was not like the grammar of prose, and that’s continued to interest me in all my own writing. So then when I got reading the “Maximus from Dogtown” poems, which is basically how the second sequence starts, the second section of the Maximus poem starts, I became really fascinated by the spiritual and mythological and cosmological aspects of that. And that became the center. [Sound Effect: Typewriter Typing] I was reading Jung for my own interest, and of course, he was big on Jung. He was reading psychology and alchemy and other things by Jung, Symbols of Transformation…

|

| 30:44 |

Audio Recording, PennSound recording of Charles Olson reading “Maximus From Dogtown I”:

|

Maximus from Dogtown — 1/ proem. [Sound Effect: Typing Sound Ends] The sea was born of the earth without sweet union of love Hesiod says// But the then she lay for heaven and she bear the thing which encloses/ every thing. Okeanos the one which all things are and by which nothing/ is anything but itself, measured so// screwing earth, in whom love lies which are unnerves the limbs and by its/ heat floods the mind and all gods and men into further nature// Vast earth rejoices,// deep-swirling Okeanos steers all things through all things,/ everything issues from the one, the soul is led from drunkenness/ to dryness, the sleeper lights up from the dead,/ [Sound Effect: Ticking Sound Begins] [Begin Gentle Instrumental Music] the man awake lights up from the sleeping.

|

| 31:48 |

Craig Carpenter: |

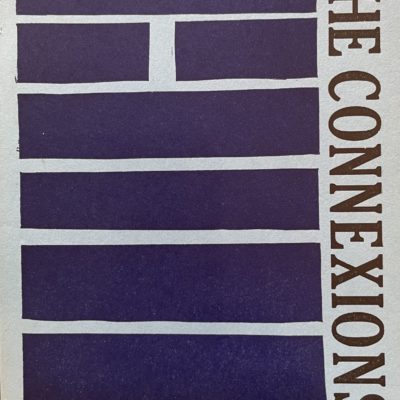

[Sound Effect: Ticking Sound merges with highway sounds and cars whooshing by] [Gentle Instrumental Music Continues] It’s the fall of 1964 and Bob, having completed his undergrad at UBC is ready to see the world. He hitchhikes to New York City via Toronto and Buffalo. There, he connects with Beat poets Allen Ginsberg, Carole Berge, and Ted Berrigan. During his final year at UBC, Bob became more involved with TISH magazine. Despite his immersion in TISH and his passion for verse, in 1964 Bob had yet to publish a book of poems. In New York, Bob writes most of the poems that make up his first book, The Connexions. His inspiration for that book—that pours out in a matter of months—is not the poetry scene around him, but a deadly illness that tears through his body. As he lies in his bed fighting for his life, poetry becomes a necessity for survival.

|

| 32:45 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Robert Hogg: |

So, when I went to Buffalo in the Spring of 1965, I had already written in New York City quite a lot of poems about my illness there. And then I continued to write about that [Ticking Sound and End Gentle Instrumental Music] when I got to Buffalo because I was actually still ill and living in the infirmary on campus. And, so, I ended up with a book of poems in my hands called The Connexions, as it turned out. So the strange thing is that that book of poems was a-hundred-percent written in New York City and Buffalo. There might have been a scrap of a poem that was written in Vancouver before I left. Because there’s one that talks about the coast range of the mountains, towards the end. But whether I actually wrote it in Vancouver or wrote it in Buffalo, I can’t remember now for sure. When some of these poets from the States came up and did read in Vancouver, they did have a strong strong effect on some of us. And I know that Duncan’s reading had a huge effect on what kind of—how I would write my poems thereafter. [Sound Effect: Sound of tape rewinding] Although I didn’t sit down and write one that was like, that emulated “Often I am Permitted to Return to a Meadow”, right, which was the poem he read that blew me away. But I know that that poem sank into my bloodstream, as it were, and never left.

|

| 33:53 |

Craig Carpenter: |

[Begin Gentle Instrumental Music] [Sound Effect: Sound of tape rewinding ends] It’s the summer of 1965, and Bob has recovered from his near death experience. He has made it down to Berkeley, California where Charles Olson is headlining the 1965 poetry conference. He carries with him a manuscript of The Connexions. [Sound Effect: Protest Chanting Sounds Begin] Amid the growing upheaval in opposition to the Vietnam War and student protests at Berkeley, the poetry conference quietly continues. [Sound Effect: Protest Chanting Sounds End] Tallman was supposed to arrange a contingent of Canadian poets to read. As it turns out, Bob is one of two Canadians and one of five tyros, as he refers to them, to read at the conference. [End Gentle Instrumental Music]

|

| 34:41 |

Audio Recording, KPFA recording of Robert Hogg reading at Berkeley Poetry Conference, 1965: |

So small falls in the Cariboo. My famous Cariboo, one of my friends anyway. Called Little Falls on South Bonaparte River. And when I was about 10 years old, we lived on a ranch in the Cariboo. And the neighbor girl was daring enough to walk across the precipice of this falls. And of course, all I could do was watch her, because I wasn’t about to walk across it too. This poem is written very recently. So it’s a memory from way back. [Begins reading poem] And the voice said, walk / Up river then / You will find her / at Little Falls / where I had left her / ankles amid flow / walking the precipice / brazen she was / not afraid to fall / or that she would fall / down / as the water as I did one fall / years later, walking up river / the rifle / clattered and fell / gouged by the rock / And I hurt my knee while hunting / I had meant to speak of an old woman / whose hair / and of a bend in the river / where / and of a tree whose leaves hang over / it was all mirrored there. [Ends poem] I’ll close the reading with a small poem, simply entitled “Song.” It’s also the last poem in this series that I have in The Connexions. [Begins reading poem] The sun is mine / and the trees are mine / The light breeze is mine / and the birds that inhabit the air are mine / Their voices upon the wind / are in my ear. [Ends poem] Thank you. [Applause]

|

| 37:13 |

Craig Carpenter: |

[Gentle Instrumental Music Begins] It’s December 2019, and I have returned once more to visit Bob at his farm. There is snow on the ground now. I can see my breath as I walk up to the door. The fields of flowing wheat that once fed his mill turned to white sheets. This time, we don’t go into the barn but straight to the attic. I sit with my old professor in his attic writing room surrounded by his poetry books. There is a generosity of spirit in the air that seems to have expanded since my last visit in the summer. I imagine the spines of his poetry books bursting with ideas beyond my own ability to name. In preparation for a reading the next night, Bob is keen to share some of his poems aloud. I try to keep quiet and listen closely. I’m hearing something more this time. [End Gentle Instrumental Music]

|

| 38:06 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Robert Hogg: |

So, this could interest you, ‘cause phonology of course is something you guys could do too, you know. [Begins reading poem] “The Phonology of Love” I speak of love/ as though it were // a word as though / it were syntactic // simply /said // oval /lips// breathe out / a gesture // lungs send / sound in a tongue curl // palatal L / down throat // a velar/ cord song // voiced / fricative // ending/ lip to enamel //teeth where/ resonant// air is /evocation // love / that is a dance of tongue// teeth and tendon / turn // breath/ into word. [Ends poem] So actually, it’s a description of the word love. These are all poems that are hopefully going to come out in this volume to be called “Postcards from America.” So these are poems that were written in Buffalo, never got published. [Craig: Yeah, they’re good. It’s good.] I think they are actually. Here’s another one…[Craig: Hot morning sun, read that one] [Bob Begins reading poem] To my friends / a hot morning sun / white for noon / through glass / waves of hot blood in my spine / line a blue vein / I go through / fluid as fire is / a kindling surge. [Ends poem] I wanted to read this poem too. It’s called “Four Seasons.” [Craig: Yeah, I was looking at that, it looks nice on the page.] Yeah, well it didn’t start like this. It started in a different form, and it started falling into tercets I’ve called them here, like little three line poems, right. Or three line stanzas. And I didn’t know what else to call them. So, and it was written quite literally by sitting on my deck, which you saw earlier. In the summer when the honeysuckles were blooming and the berries were falling. [Begins reading poem] First white and pink flowers / now little red berries / fall from the honeysuckle / onto our cedar deck / Next leaves browning / with summer sun / soon abundant snow [Poem Ends] [Bob Laughs] Which is what we’ve got now! [Craig: Yeah] Yeah. So there was the four seasons. Like I was just like sitting there…

|

| 40:22 |

Audio recording, Poetry reading at the Carleton Tavern in 2019, Ambient Sounds:

|

[Bob’s voice fades into a recording from the poetry reading the next night. We hear the sounds of people talking before the reading as Craig’s narration begins.] |

| 40:27 |

Craig Carpenter: |

The next evening, Ottawa’s poets congregate in the back room on the second floor of the Carleton Tavern.

|

| 40:33 |

Audio recording, Poetry reading at the Carleton Tavern in 2019, rob mclennan: |

I’m not waiting for him. Thank you very much for coming to this, to our little annual event. The Peter F. Yacht Club, you know, holiday extravaganza. You’ve got to start calling it that, that would be cool. There are books in a book table…

|

| 40:47 |

Craig Carpenter: |

[Audio recording of rob mclennan speaking continues under narration] rob mclennan has invited Bob and other local poets to read at the annual above/ground press Christmas party. Bob tells me rob has mellowed with the years. Perhaps he has recognized his own gift to the community I think—his dogged persistence of publishing so damn much, now a document of the moving of time through the eyes of poets. The room is packed pre-pandemic style. Beers are flowing. The scene reminds me of my time here in the 90s. rob mclennan sits at a table registering the evening’s readers. When I approach to say hello, in typical fashion with a mocking gasp, he points out just how much I have aged. His signature long hair and goatee whiter now. But he’s the same lowercase rob mclennan. And, it’s true, he has mellowed. Or maybe it’s me who’s mellowed. Either way, I find myself happy to see him and smiling as he introduces the evening. [Begin Gentle Instrumental Music] As the night draws to a close, a few of us head to a cafe for some food and drink. I think about the poets—all their poems still jangling around in my heart and mind. It was a good night. This is Bob’s community. It’s mine too. Poets don’t much like to form alliances. So, when poets do come together to create books, magazines or events like tonight’s—something turns. It’s hard to mark time. Like sound, we cannot pause it. It keeps passing. As I listen to Bob recite a poem he has dedicated to Bob Creeley called Dig-it, I sense time turn. It turns in widening circles of return.

|

| 42:44 |

Audio Recording, Robert Hogg interview with Craig at Mountain Path Farm, Robert Hogg: |

[Gentle Instrumental Music Continues] Here. Can I read this one? [Craig: Please do.] This one’s called “Dig-it.” [Craig: Now, this is for Bob Creeley.] This is for Bob Creeley. I wrote it last night, or yesterday sometime. [Craig Laughs] Had nothing to do with today, it was just one of these things that came to me. Bob Creeley was always saying, dig it, dig it, you dig it, dig it—right? But if you take the hyphen out, it becomes a different word. Alright. So, “Dig-It” for Bob Creeley. [Begins reading poem] 11:11 my clock reads / 1 1 1 1 / marching across / the face of it / twice a day / just like that / marking time / we say / standing in one / place / one / minute / marking time [Ends Poem] [Bob laughs]

|

| 43:35 |

Original Music Score by Chelsea Edwardson:

|

[Gentle instrumental music rises and fades into outro narration.] |

| 44:19 |

Hannah McGregor: |

[Start Music: SpokenWeb Podcast Theme Music, Instrumental Overlapped with Feminine Vocals] SpokenWeb is a monthly podcast produced by the SpokenWeb team as part of distributing the audio collected from and created using Canadian literary archival recordings found at universities across Canada. This episode was written, produced, sound-designed and voiced by Craig Carpenter, with additional audio courtesy of the SoundBox Collection, PennSound, and KPFA. The musical score was composed by Chelsea Edwardson. Special thanks to Karis Shearer, Robert Hogg, Deanna Fong, Mathieu Aubin, Marjorie Mitchell, and Judith Burr for their feedback on drafts of this episode. Our podcast project manager and supervising producer is Judith Burr. To find out more about SpokenWeb visit SpokenWeb.ca and subscribe to the SpokenWeb Podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you may listen. If you love us, let us know. Rate us and leave a comment on Apple Podcasts or say hi on our social media @SpokenWebCanada. Stay tuned to your podcast feed later this month for ShortCuts, a new take on audio of the month with Katherine McLeod, mini stories about how literature sounds. [End Music: SpokenWeb Podcast Theme Music, Instrumental Overlapped with Feminine Vocals]

|