| 00:18 |

SpokenWeb Podcast Theme Music: |

[Instrumental Overlapped with Feminine Voices] Can you hear me? I don’t know how much projection to do here.

|

| 00:18 |

Hannah McGregor: |

What does literature sound like? What stories will we hear if we listen to the archive? Welcome to the spoken web podcast: stories about how literature sounds. [End Music: SpokenWeb Podcast Theme Music] My name is Hannah McGregor, and each month I’ll be bringing you different stories of Canadian literary history and our contemporary responses to it created by scholars, poets, students, and artists from across Canada. There’s a kind of magic to finding an old recording and listening to the sounds of the past. When researchers listes to archival recordings, each sonic literary record comes with silent questions: who is speaking and who is recording? Where was this recording made? And, what are those background sounds? How are we listening to and interpreting the recording in the present and how might people have listened differently at the time the recording was made? How can we preserve this physical tape so it’s protected for future listeners? In March of this year, SpokenWeb researchers, Kate Moffatt, Kandice Sharren, and Michelle Levy brought us a full audio edition of Mavis Gallant, reading her short story ‘Grippes and Poche’ at Simon Fraser University in 1984.

|

| 01:44 |

Hannah McGregor: |

Now we bring you part two of the series, an exploration of the questions that surround this recording of Mavis Gallant. Kate, Kandice, and Michelle refer to these as the ‘paratexts’ of the recording. And their illuminating investigation takes us back to the year 1984 and the days surrounding Galant’s presence at the SFU podium. The stories that they uncovered are surprising and often delightful, and they help us listen to Gallant’s reading with fuller awareness of the realities that surrounded the event. Here are Kate, Kandice and Michelle with episode nine of the SpokenWeb Podcast, “Mavis Gallant Part Two [Start Music: Piano Overlaid With Distorted Beat] The ‘Paratexts’ of “Grippes and Poche” at SFU. [End Music: Piano Overlaid With Distorted Beat]

|

| 02:34 |

Ann Cowan-Buitenhuis: |

The event on campus was free, but we were supposed to be making money downtown, so we charged everybody $10 and I came out of the room and I said, “Carolyn, she just told everybody that you’d give them back their $10!” And Carolyn said something like, “Well, I don’t have it. I took it down to the office.” So anyway, [Accordian/French interlude music] it was one of those ones…

|

| 02:58 |

Kate Moffat: |

On March, 2021. We – Kate Moffat, Kandice Sharren, and Michelle Levy presented Mavis Gallant reading of her New Yorker short story ‘Grippes and Poches; as an episode of the SpokenWeb Podcast – [Sound Effect: Opening Tape Recorder]

|

| 03:12 |

Audio Recording, Mavis Gallant: |

I’m a fetishist. That’s why the watch has to be there and not there. And you see that’s …

|

| 03:15 |

Michelle Levy: |

[Clips of audio layered] …at the time of this SFU reading Gallant….

|

| 03:17 |

Kate Moffat: |

…the recording provides us with an offering…

|

| 03:19 |

Kandice Sharren: |

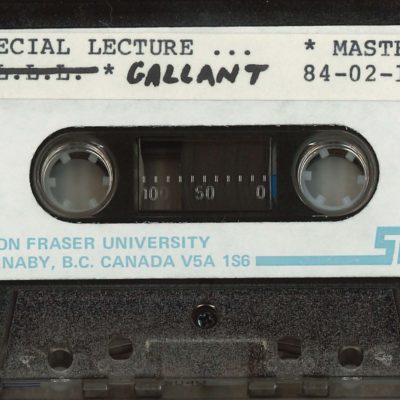

… the audio cassette containing this recording is housed in…

|

| 03:21 |

Audio Recording, Mavis Gallant: |

Can you all hear me? [Sound Effect: Opening Tape Recorder]

|

| 03:24 |

Kate Moffat: |

While we were preparing our last episode, we used our grounding in book history methodologies to think about the recording as an unofficial audio edition of “Grippes and Poche”, in which Gallant’s explanatory asides take on a role similar to that of footnotes or endnotes. In our last episode, we noted, however, that unlike footnotes or endnotes, listening to Gallant’s asides were not optional, but integrated into the text. Something paratextual became textual, so to speak [End Music: Accordion]

|

| 03:51 |

Kandice Sharren: |

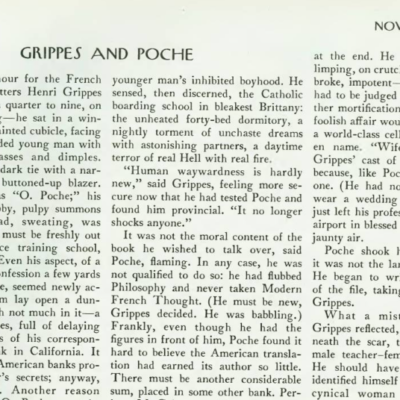

While putting together the second episode, we were curious about exploring the relationship between the text and the paratexts of the reading further. Paratext was coined by Gérard Genette to describe everything that surrounds a text, including the material form the text takes, contextual information about the author, and even book reviews and interviews. Genette talks about paratexts as “thresholds of interpretation”, that is to say that they fundamentally shape how we approach, encounter and engage with the text. For the original print version of “Grippes and Poche” in the New Yorker, it’s paratextual material would include the cartoons interspersed throughout the text, other articles that appeared alongside it, and even the magazine’s signature font. These paratexts established Gallant’s story as a self-consciously literary work, one that carries with it a certain amount of prestige. In dealing with an audio recording of a text, we had to expand our idea of what a paratext might be. In the case of Gallant’s reading, the paratexts include the audible and inaudible contexts that surround the event and inflect how we interpret the story. The circumstances that surrounded Gallant’s visit, the planning that went into the reading, Gallant’s delivery, the audience, and even the tape that holds the recording.

|

| 05:12 |

Michelle Levy: |

Interested in supplementing the archival materials we found with human memory to reconstruct the event and its paratexts, we sought to make these paratexts visible by talking to Ann Cowan-Buitenhuis and Carolyn Tate, who worked in the liberal studies department at SFU and were involved in organizing the Mavis Gallant events during her visit. I also spoke at length with Grazia Merler, a friend of Gallant’s who worked in SFU’s Department of Languages, Literature, and Linguistics at the time of the event. [Start Music: Piano] From these investigations, we have assembled a series of conversations and artifacts to contextualize the audio recording of the reading you heard in the first part of this two-part series. To establish the paratext of this reading, we asked the following questions, which structure this episode.

|

| 06:03 |

Kandice Sharren: |

First, what were the circumstances of Gallant’s visit to SFU in 1984? Second?

|

| 06:10 |

Kate Moffat: |

What do we know of the reading the day before otherwise known as the fiasco?

|

| 06:16 |

Michelle Levy: |

Third, how do we place Gallant’s accent and understand her pronunciation choices?

|

| 06:21 |

Kate Moffat: |

Fourth, who are the unseen, but audible audience members for the reading?

|

| 06:27 |

Michelle Levy: |

Fifth, why did she select ‘Grippes and Poche’ to read to this academic audience?

|

| 06:32 |

Kandice Sharren: |

And finally sixth, what physical artifacts of the events survive and what do they tell us about the event?

|

| 06:39 |

Kandice Sharren: |

Chapter One: The Visit, in which Michelle talks to Grazia Merler and Gallant’s reason for visiting Vancouver becomes clear.

|

| 06:54 |

Kate Moffat: |

Following our close listening to the recording of Gallant’s reading for our last episode, we were curious about the circumstances that brought Gallant to Vancouver in 1984, given that she lived in France for most of her life. In addition to chatting with Ann and Carolyn, Michelle was able to connect with one of Gallant’s old friends,

|

| 07:10 |

Michelle Levy: |

Gallant was invited to SFU by Grazia Merler, then an Associate Professor in the Department of Languages, Literature, and Linguistics on the recommendation of her supervisor, Merler had met Gallant while researching her PhD on Stendhal In Paris in the early 1960s. Merle told me about how she was invited to Gallant’s apartment at [French addresss] in Paris for tea. Upon arriving on a frigid day in the middle of winter, Gallant asked Merler if she wished for tea or something stronger. Merler agreed that something stronger would be welcomed. They hit it off immediately and remained friends until Gallant’s death in 2014,. Gallant lived in the same apartment in the sixth arrondissement for over four decades, from 1961 or 62 until her death. Merler told me that Golan came to visit her when SFU was first being built, and she references this first visit in her introduction for Gallant at the Burnaby event.

|

| 08:07 |

Audio Recording, Gratzia Merla:

|

I talk a little bit louder. Can you hear me now?

|

| 08:09 |

Audio Recording, Audience Member: |

That’s fine. Thank you.

|

| 08:11 |

Gratzia Merla: |

In 1965, before Simon Fraser University opened, I took a friend to the top of this mountain to show her a striking piece of architecture and the awesome site or this architecture. At that time, we both decided that we should come back to see the development of what seemed at that time a master temple. I kept my promise about 15 years ago. Mavis Gallant was the other part in the promise, and she’s keeping her part of the bargain today.

|

| 08:56 |

Kate Moffat: |

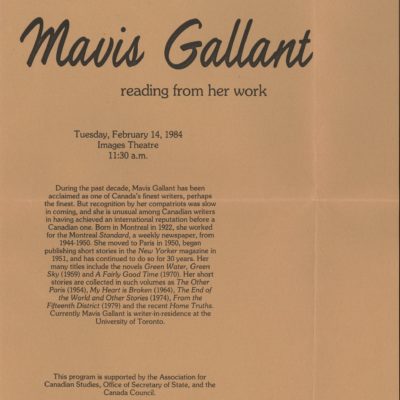

As we know from the recording of ‘Grippes and Poche’, Gallant visited SFU again in 1984, to give her reading on February 14th. The poster for the reading tells us that Gallant was, at the time of the event, writer in residence at the University of Toronto. She likely took advantage of her relative proximity to Vancouver to make good on her promise to return.

|

| 09:15 |

Michelle Levy: |

Merler told me that during this period Gallant came regularly to North America. She was being paid well for her New Yorker stories and could afford to visit friends in Montreal, as well as her editor, William Maxwell, in New York. From what we’ve been able to gather, it seems Gallant gave a number of readings at universities in Canada during this time. In addition to the SFU reading of Grippes and Poche in 1984, she also gave a reading of the same story in June of that same year at the University of Toronto, a reading of her story ‘Virus X’ at the University of Alberta in 1975, and reading at the University of Victoria, although we haven’t been able to track down a date or the story she read for that event. [Start Music: Upbeat Piano][Sound Effect: Flipping Through Pages]

|

| 10:00 |

Kate Moffat: |

Chapter Two: The Fiasco. In which attendees and organizers Ann Cowan-Buitenhuis and Carolyn Tate meet Mavis Gallant, and an event goes terribly wrong.

|

| 10:13 |

Michelle Levy: |

I was hoping that you could each just introduce yourself briefly and maybe tell us a little bit about where you are now and where you were in 1984. Carolyn, do you want to start?

|

| 10:24 |

Carolyn Tate: |

Sure. Well, right now, I’m in my dining room in Toronto, Ontario in the Bloor West Village. I’ve lived in this house for about 20 years. At the time Mavis was in Vancouver I was the director of Liberal Studies – the Liberal Studies program for Continuing Studies, and I was the person who was responsible for organizing the downtown part of her visit. And as we’ll discover, it was complete fiasco. But really my main reason I’m here is I’ve been a tremendous fan of Mavis Gallant for many years. And maybe I should add that since Continuing Studies, I went to law school and I practiced intellectual property law for 20 years.

|

| 11:10 |

Michelle Levy: |

Wonderful! Well, thank you so much. Ann, do you want to tell us a little bit about you now and where you were?

|

| 11:17 |

Ann Cowan-Buitenhuis: |

Well, now I’m sitting in my study in Vancouver. I live in the West End near Stanley Park and I’ve lived here for a while. But in 1984, I was in Continuing Studies at Simon Fraser and Carolyn came to join us. I think she came a couple of years after I did, and we became great friends. And we had babies together. I had one, she had one, I had one, she had one. So we – the same maternity clothes were floating around the office for almost five years, which drove everybody nuts. But anyway, so we’d been friends all these years. I did my BA at U of T in English – English Language and Literature it was called then. And then I did a Master’s degree in Carlton because I was married to – at that time a physiology professor who had a job at the University of Ottawa. But then I fell in love with Peter Buitenhuis and moved to Vancouver and started working at SFU about a year after that. So – and Peter was the chair of the English department at the time that this recording was made…

|

| 12:35 |

Kandice Sharren: |

It was through our conversation with ann and Carolyn that we learned that Mavis Gallant’s visit to SFU actually included two events: the reading of ‘Grippes and Poche’ at SFU Burnaby at Images Theater at 11:30 in the morning of February 14th, which we have a recording of, and a mid day reading downtown the day before for which we have no archival material whatsoever. In fact, we were unaware of the event on February 13th until we had the opportunity to chat with Ann and Carolyn about their experiences organizing and attending these events.

|

| 13:09 |

Ann Cowan-Buitenhuis: |

Well, first of all, you’re quite right. There was an event downtown. It was the day before the event on campus. And it was in quite a small room because we were at 549 Howe in those days and we didn’t have any large rooms. So we did – as Carolyn said, she organized the downtown talk and neither of us can remember what story she read downtown. It was not the same one as she read on campus. But I think Carolyn should tell you a little bit about that event because some of the behaviour of Mavis in the recording of the second event, I think stems from her experiences downtown. So maybe Carolyn would talk a little bit more, because you were really in charge of that event. And I certainly remember the room being full of very enthusiastic people.

|

| 14:00 |

Carolyn Tate: |

I’m happy to talk about the downtown event and Mavis. It was a fiasco, frankly. I didn’t think that there would be very many people and we had this little free room down there and somebody set up the mic and I thought, well fine. You know, 20 people will come or something like that. Well, more like 50 or so people came and the room was very crowded and we didn’t have the technician – he had set it up, but then it didn’t work. So it was really quite miserable for everybody, but especially for Mavis. She was very, very put out by it. And in truth, I was a little bit put out by how put out she was. I expected her to be this kind of, I don’t know, nothing would phase me sort of person. And really, she wasn’t that at all.

|

| 14:51 |

Carolyn Tate: |

She was very proper. She was very neatly dressed in a very good French suit. She’d come on the airplane and she told us that she had a terrible time because she didn’t want to ask somebody to help her get her suitcase down from the bin. And you know, you couldn’t just ask somebody to help you – didn’t you know? And frankly, I didn’t know that [Laughs]. I thought – I really thought she was a bit precious. I have to say. [Laughs] But, notwithstanding that, she came along and we were going to do the talk and there was no mic. So she had to shout the whole time, and she did. And she finished, she gave her reading and people heard her. I have to say – I was so fritzed by that time that I didn’t, I didn’t know – I have no idea what story she read. I have no memory of her actual talking, which was why I was so thrilled with the recording that you have because I think she is a brilliant speaker.

|

| 16:04 |

Ann Cowan-Buitenhuis: |

Well she was a little grumpy, I have to say. And she – not only was she grumpy, she told everybody to ask Carolyn for their money back, which was $10. The event on campus was free, but we were supposed to be making money downtown. So we charged everybody $10 and I came out of the room and I said, “Carolyn, she just told everybody that you’d give them back their $10.” And Carolyn said something like, “Well, I don’t have it. I took it down to the office”. So anyway, it was one of those moments. But the reason I mentioned that is that the next day, you’ll notice, she says several times on the recording, “can everyone hear me? Can everyone hear me?” And the thing is that she wasn’t a very large person and she had a not particularly strong voice. So I think that having exercised her voice to the max the day before she was a little bit overly nervous on that recording about how well she was being heard and so on. And she was fussing if you remember, at the beginning, she was fussing about the microphone and so on. And I I think she was nervous about technology in the same way that both Carolyn and I are. So, we have to forgive her that. [Start Music: Upbeat Piano]

|

| 17:24 |

Kandice Sharren: |

[Sound Effect: Flipping Through Pages] Chapter Three: Mavis Speaks, in which we try to pin down Gallant’s accent.

|

| 17:31 |

Kate Moffat: |

Despite Ann’s memories of Mavis being somewhat grumpy and nervous about her delivery, we all agreed upon listening to the recording that it was rather brilliantly done. She’s an engaging and dynamic speaker and one who is perhaps more self-conscious or aware of the unique elements of her delivery than her audience. In the short question period following the reading, someone in the audience asks a question, barely audible on the recording. Gallant’s response indicates she heard him mention a mistake, and contextualizes her various pronunciations of Grippes and Poches throughout the reading, which she clearly considers as slips of the tongue.

|

| 18:02 |

Audio Recording, Audience Member: |

But in this context, you committed the best kind of blunder, which revealed a bit of your personality to us.

|

| 18:08 |

Audio Recording, Mavis Gallant: |

What kind of blunder?

|

| 18:10 |

Audio Recording, Audience Member:

|

Revealing your personality.

|

| 18:12 |

Audio Recording, Mavis Gallant: |

Oh! I thought you were talking about pronunciation because when I’m reading in English in English, it’s almost impossible for me to pronounce French names in French because you have to change the pitch of your voice, you know, and it’s a different pitch, the two languages, and it interrupts the reading. And that’s why I say Grippes, Grip, Grips, just as it comes most easily, I thought you meant that [Laughs].

|

| 18:35 |

Michelle Levy: |

Gallant’s remarks on her uneven pronunciation of characters’ names reveals her position between English and French and between Canada and France, not just in her adult life. All of us had strong responses to Gallant’s accent, which we struggled to place until Ann and Carolyn compared it to that of Pierre Elliott Trudeau, who also grew up bilingual in Canada during the 1920s and thirties. Like the New Yorker’s font, Gallant’s accent conveys particular contextual information about her and her place in history.

|

| 19:08 |

Carolyn Tate: |

I wanted to ask you what you thought of Mavis’ accent, if you had any, do you have any reaction to that? Because I found her accent quite amazing, sort of mid Atlantic. It didn’t sound totally Canadian. It didn’t sound British. It’s kind of, she kind of reminded me a bit of the way Pierre Trudeau talked, it was just its own thing. And I don’t know whether you had a reaction to that or not.

|

| 19:42 |

Michelle Levy: |

I think we had trouble –I had trouble placing it. And I remember discussing that with Kandice and Kate. I asked my husband about it [Laughs], I was like, “where is this voice coming from?” It did seem really unusual. Lovely. One of my favourite stories of hers called ‘Specs Idea’, which is from around the same time, it was in that same volume, and it’s about an art dealer. There’s this woman that owns the art that her husband has left her, and her voice is described as like trilling bells. And I always feel like that to me, that’s almost like Mavis’ voice. It’s – I thought it was beautiful. But the accent, I just, I had no idea.

|

| 20:25 |

Ann Cowan-Buitenhuis: |

Well, it’s –I think that you mentioned that she was educated in French, but her English became the language of literature for her. So I’m wondering if, as Carolyn said, Pierre Trudeau had a bilingual early childhood as well. And I’m wondering if that’s a West Mount Montreal or [French word] accent or something like that.

|

| 20:51 |

Carolyn Tate: |

I think so. I mean, that’s what I thought. I mean, his mother was –Trudeau’s mother was an Anglophone and of course, Mavis’ parents were Anglophones too, but she had this French education. [Start Music: Piano] |

| 21:04 |

Kate Moffat: |

Chapter Four, The Unseen Audience. In which we learn about bums in seats, how many there were, where they sat, how they laughed. [Sound Effect: Flipping Through Pages] Our listening to the recording and our reactions to what we could hear of the event, the story, and her voice, and accent were necessarily mediated by the recording and our own personal circumstances listening to it, which differ greatly from the live experience that the audience of the reading had. Ann realized while listening to our last episode, that she could hear her husband in the audience during the reading.

|

| 21:37 |

Ann Cowan-Buitenhuis: |

And it was really kind of spooky for me because when I listened to the recording, I could hear Peter laughing. And I haven’t heard it for so long.

|

| 21:50 |

Audio Recording, Mavis Gallant: |

No action chapter to the abstract essence of risk. [Audience member laughs] The professor, one.

|

| 21:57 |

Ann Cowan-Buitenhuis: |

One of the wonderful things about Peter was that he always laughed very loudly and the kids would always say their school plays went better on the days when he was there, cause he would laugh at all the jokes.

|

| 22:08 |

Kate Moffat: |

Listening to the recording, we have no information about the audience except what we can hear. With Ann’s input, We know Peter Buitenhuis, chair of the English department at the time, was in attendance, and also the longer personal history of his laugh. And this prompted a general curiosity about the audience, including how many people attended, and thus how full the very large Images Theater might have been, which isn’t something recorded in the archives. |

| 22:32 |

Carolyn Tate: |

Yeah, I think that the Burnaby audience was not bad. I think we probably– that theater is good. I think we persuaded people to sit near the front and to kind of group, but I think that the theater would have been three quarters full. And I think that theater holds over 200 people.

|

| 22:51 |

Kate Moffat: |

In asking about and considering both our own reactions to the reading and the audience, we wondered how our reception of it might’ve differed or not from that of the individuals attending the event, who we hear occasional rumbles of laughter from

|

| 23:04 |

Audio Recording, Mavis Gallant: |

…Anglo-Saxon commercial English [Audience Laughter] shared with some cats he had already tried to claim as dependents [Audience Laughter] He showed…

|

| 23:16 |

Michelle Levy: |

Now from the talk itself you mentioned, Ann, that there were, that Mavis was asking questions at lunch about how you felt it went, and I’m wondering how you felt it went during the talk itself. I mean, it sounded again from the recording, which we’ve all heard, like it was crystal clear. So it sounds like the –some of the issues that happened the day before didn’t happen, but did you get a sense people were laughing, people were getting the jokes, people were enjoying it?

|

| 23:49 |

Ann Cowan-Buitenhuis: |

Yes, I certainly did. And, I was listening to the responses as the talk went on. I think the story was a bit long, quite frankly. I think –there’s a point where she tells you she’s reading from proofs and that her editor had a query. I mean, is he thinking, is this in his head or is that actually happening? So – and I had had the same thought myself, like, wait a minute, is this in this guy’s head? Or is he actually having this conversation? Or what have you. And I realized that I had drifted off, listening to the recording, and my recollection in the talk itself was that it was quite a long story. I felt at the time. And I think – but I do think people got it and there was still enthusiasm. But my recollection also is that the university classes were programmed in such a way in those days. The scheduling was done in such a way that there was a certain period of time in the middle of the day that you could fill with an event and people would have to go to class if it went too long. So I remember having a little bit of anxiety because I figured having observed her behavior the day before, if people stood up and started leaving, she was not going to be happy. So, I think I had a certain amount of nervousness about how long it was and – no concern about people’s lack of interest – but just a little bit of event planner angst I guess.

|

| 25:21 |

Michelle Levy: |

That people would have to leave. [Laughs] Yeah.

|

| 25:23 |

Kandice Sharren: |

[Start Music: Upbeat Piano] [Sound Effect: Flipping Through Pages] Chapter Five: Choosing ‘Grippes and Poche’, in which we reconsider Gallant’s story in light of the audience she performed to and are deeply unimpressed with Henri Grippes.

|

| 25:45 |

Michelle Levy: |

One of the things that I find most fascinating about paratexts is that they don’t just work one way. Artistic choices are made anticipating a certain format of publication. When we’re talking about print, it can be hard to pin down how involved an author was in the design of, say their book. Although we do know that Gallant wrote many of her stories specifically for the New Yorker, meaning that she would have been aware of the format her stories would be published in. Again, down to the font, although probably not the cartoons.

|

| 26:15 |

Kandice Sharren: |

In the case of a reading though, it’s a lot easier to see how a writer might be responding to their immediate context, which led us to ask: why did Gallant select this story to read to her SFU audience in 1984? As you may recall, in her introduction to the reading, Gallant describes her story as a “gentle send-up” or satiric commentary.

|

| 26:37 |

Audio Recording, Mavis Gallant: |

Henri Grippes is an imaginary French Parisian writer who has occupied four or five stories that I have published with his friend, the British writer, Victor Prism. They’re entirely imaginary. They’re not based on anyone in particular. It was just a very gentle send-up.

|

| 26:59 |

Kandice Sharren: |

She may have chosen the story for its delicate comedy, as she sends up French bureaucracy, as we meet the hapless and misinformed tax agent, O. Poche and Henri Grippes with his secret apartments and tax evasion. The main object of her send-up seems to us to be Grippes as writer. As Jonathan Coe noted in the London Review of Books in 1997, “Grippes is one of her most memorable characters, a shallow opportunistic writer who nevertheless, somehow manages to elicit the reader sympathy by virtue of his rotten luck and his chronic unpopularity with the book buying public. There’s a mordant redeeming humor here, which has given free rein then in Gallant’s weightier stories.”

|

| 27:41 |

Michelle Levy: |

Does he elicit the reader’s sympathy though? I have to say, as someone who rents in Vancouver, I am hard pressed to want to spend time looking for a slumlord’s redeeming qualities, especially when it’s paired with literary opportunism. I really found myself hoping that Poche would catch him out by the end. So hearing Ann and Carolyn discuss the reading really struck a chord with me in part, because I kind of agreed with Carolyn’s assessment of the story.

|

| 28:09 |

Carolyn Tate: |

Yeah. I’m kind of surprised, ann, that you say that people received the story well, and that they laughed and whatnot because I found the story of a bit dismal. I think of it, she mentions Flaubert, as I was saying to Kate at some point during the story, and I feel that this was her kind of her Flaubertian moment or something. And it kind of reminded me of that novel the [French book title] by Flaubert where he has the ex-bureaucrat and somebody else doing all of this extremely grotesque kind of pseudo literary stuff. And I found that when I read the story, it dragged quite a lot and I didn’t find it all that amusing. And I think of it also as sort of the beginning of the end of her North American kind of– well, maybe I’m wrong about this because I think that North American readers were fascinated and gripped by these expats that she wrote about. I don’t think they were so interested in French bureaucrats and you know, French literary life and who is this English writer anyway, you know? Anyway, as I say, I don’t think it’s her best moment. Although because of this literary aspect of things, I’m going to read the other Henri Grippes stories and see whether, you know, they kind of interest me more now that I thought a little more of a take on this kind of this world.

|

| 29:38 |

Michelle Levy: |

Carolyn, if you read the rest of the Grippes story, you will indeed find much more on this kind of the French literary scene – corruption may be a bit strong, but there’s a really hilarious whole story about this attempt to write an encyclopedia of French authors that drags on for decades because they’re constantly changing who they think is important and who should be included, and the editors keep fighting with each other.[Laughs] It’s really funny. So there’s definitely more of that in that series of stories about the writer.

|

| 30:13 |

Carolyn Tate: |

I did read them sometime, but that’s very Flaubertian too. That’s what this –I don’t know whether you’ve ever read this, [French book title], it’s a terrible thing actually, but this is their whole thing too. They’re trying to be more and more kind of literary and correct, and all the rest of it. And it’s a complete balls up, frankly. [Laughs] I think Henri, he’s sort of in that frame somewhere.

|

| 30:44 |

Michelle Levy: |

That said, and in Carolyn’s discussion of the literary trends of the 1970s and 80s,, a period that I didn’t live through and haven’t paid much attention to either academically or in terms of its literary culture, but one that ‘Grippes and Poche’ engages with did help me appreciate what exactly this story was doing.

|

| 31:04 |

Kandice Sharren: |

I was struck by the sexual politics of the story, and particularly Gallant’s deadpan, imagining of a very capital P problematic male writer. Grippes regrets that in his American novel, he resorted to the stale male teacher, female student pattern. Could this failed attempt to write a novel about an academic romance be the reason for her choice?

|

| 31:27 |

Audio Recording, Mavis Gallant: |

… female student pattern in the novel. He should have turned it around, identified himself with a brilliant and cynical woman teacher. Unfortunately, unlike Flaubert with his academic stocking horse, he could not put himself in a woman’s place, probably because he thought it an absolutely terrible place to be. [Audience Laughs]

|

| 31:48 |

Kandice Sharren: |

This line elicits a knowing laugh from the audience. In fact, Gallant had been one of the first to write about a real life female teacher, male student affair between a 32 year old Gabriel Roussier and her 16 year old pupil for the New Yorker in 1971. It was a story that scandalized France, when it broke in 1967, as the parents of the boy brought legal proceedings against Roussier, that resulted her in her imprisonment, and that brought about her suicide in 1969. As Gallant dryly points out in her article about the affair, the story was an old one rife with the double standard, reflecting what Gallant calls “a prevailing belief that Don Juan is simply exercising a normal role in society, whereas women have been troublemakers ever since Genesis.” ‘Grippes and Poche’ ends on a note of implicit violence as Gallant relates Grippes storytelling as a process of stocking and confining one of his female characters. In her reading, she slows down to relate his menacing attempt to invent a female character.

|

| 32:57 |

Audio Recording, Mavis Gallant: |

He had got the woman from church to dining room and he would keep her there trapped, cornered, threatened, and watched until she yielded to Grippe and told her name.

|

| 33:08 |

Kandice Sharren: |

Thus ending the story on a more ominous note than the gentle send-up with which it begins.

|

| 33:14 |

Michelle Levy: |

The story is commentary on sexual politics in a campus environment, complimented her location and audience. In our conversation with Carolyn and ann, they speculated that the academic satire within Grippes and Poche, maybe one of the reasons why Gallant selected this story for her on-campus reading.

|

| 33:32 |

Carolyn Tate: |

Don’t you think she was a brilliant reader on campus?

|

| 33:36 |

Ann Cowan-Buitenhuis: |

I do. And I was thinking about the context of that story: 1984. And I kind of – I was thinking, what else was being published at the time? And it was interesting that she was sending up the campus drama, the campus romance, the professor who falls in love with the student – and remember he had written a failed novel. It wasn’t quite good enough in that genre. And so I was thinking who was writing in that genre that time? And I remember David Lodge’s trilogy – do you remember? And they were so good. They were so good. And so I think, she was sort of sending up professors and sort of commenting a little bit on David Lodge’s three books, which were Changing Places in 1975, Small World – an academic romance in 1984 – and Nice Work in 1988. |

| 34:33 |

Ann Cowan-Buitenhuis: |

And the other thing too I found was – as Carolyn said earlier –just the vagaries of literary tastes. People going in and out of fashion and suddenly being reinvented as somebody who’s okay with women, at a time when, when suddenly we’re worrying about whether or not somebody has the right feminist credentials to be read by the students in women’s studies, et cetera. So I think that there was certainly a memory for me of literary tastes and fashions and so on that I found quite interesting hearing the story again. None of this occurred to me particularly at the time.

|

| 35:19 |

Kandice Sharren: |

It’s something that testament to these vagaries of literary trends that I had actually never heard of David Lodge before. Apparently this shocked Michelle who asked me if I was sure I wanted to admit to this publicly. When I think of campus novels, I think of on the one hand, Dorothy Sayers Gaudy Night published before the outbreak of the Second World War, or on the other hand, Zadie Smith’s On Beauty and Sally Rooney’s Normal People. But I haven’t really read any written between the Second World War and the early 2000s, perhaps because the sexual politics of novels written in that period speak to a very different historical moment, and one that isn’t the subject of nostalgia, the way something like Sayers book is.

|

| 36:05 |

Michelle Levy: |

The literary context of this story are only part of it’s satire though. Grippes refashions the dull civil servant in an attempt to keep up with literary fashion, but also with the winds of political change. The beginning of the story is set in 1964 and ends in the early 1980s, thus tracking both the progress of Grippes writing career and that of the fifth Republic itself.

|

| 36:29 |

Ann Cowan-Buitenhuis: |

The other thing though, I thought that was interesting about the story was how she talked about the change in government and this story spans 20 years or something. And so you have those [French phrase] coloured folders and you have the Charles DeGaulle coloured folders and so on. And the poor old tax guy gets his baby face gets sterner, and he got some little bald spot in his curls and so on. And so there’s a sense of a time passing. To me that sort of Proustian, and maybe that was a kind of melange of that as well. I really haven’t thought too much about what she might’ve been trying to accomplish in terms of her own oeuvre, but she had published that some years before she read that story. So it certainly wasn’t new work she was reading. But I have a feeling she kind of hauled out something that she thought might appeal to an academic audience. And the question that you asked…

|

| 37:34 |

Michelle Levy: |

Despite the literary and political moments that Gallant’sstory is in conversation with, her language has a strikingly timeless quality, precisely descriptive, but with a wry restraint that ironically captures the rhythms of Grippes thoughts.

|

| 37:47 |

Kandice Sharren: |

In writing about a writer, Henri Grippes, Gallant celebrates his flights of imagination, but also wryly observes his limitations. The meta-fictional elements of the story are both profound and comic as we are treated to a description of Grippes entire oeuvre, and also to his inability to recognize himself in his characters. On contemplating the protagonists of his books, Gallant dryly explains that…

|

| 38:13 |

Audio Recording, Mavis Gallant: |

He was like a father gazing around the breakfast table, suddenly realizing none of the children are his.

|

| 38:18 |

Kandice Sharren: |

This was something that Ann commented on too.

|

| 38:21 |

Ann Cowan-Buitenhuis: |

I thought she had some wonderful metaphors and some wonderful sentences. I mean she talks about the shoreline of the 80s at one point –and talking about the rise to acclaim as this man’s career is a little bit rejuvenated at the end of the 80s. And she had just lovely, lovely metaphors from time to time and quite extended – she’d spin it out in kind of interesting and droll ways. And so I really admired her as a wordsmith in this story. And– as I said earlier, I did feel it was a rather long story, but I felt that her language – I had forgotten what a fine craftsman she was. [Start Music: Piano] She really, she really does write in a very original and refreshing way

|

| 39:26 |

Kandice Sharren: |

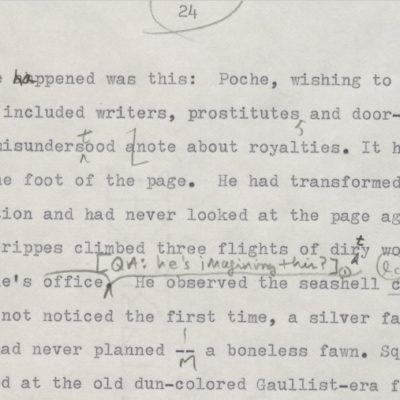

Chapter six: Grippes and Poche in the archive, in which Ann remembers the reel-to-reel machine at the reading and a hunch is confirmed. [End Music: Piano] Listening to Gallant’s original and refreshing language in her own voice is only possible through the archival remains of the event, especially their high-quality. In the March 2021 episode we talked about how these archival materials –in this case, the tape that holds Gallants reading – reveals the hands that manipulated it. The clean break between sides one and two had us convinced that despite the fact that the tape said “master” on it, it was actually an edited copy of what had most likely been a reel-to-reel recording.

|

| 40:11 |

Kate Moffat: |

We were delighted to hear Ann confirm some of what we questioned and hypothesized in the first episode surrounding Curtis Vanel’s involvement. In a subsequent email, she shared with us that “the sound technician was set up on the right side, facing the stage and had a desk with reel-to-reel recorder. I always paid to have the technician there. Otherwise someone else had to make sure the record button was pushed and that the thing was at the right level. The technician also made sure the audio levels were good. I have a vision of Curtis walking up to the mic, turning it on and checking, and then adjusting the height for Mavis, and then sitting down. He would have done the same for Grazia.” She even recalled that Vanel was particularly interested in generations of recordings. His master tape was the one that other generations were created from.

|

| 40:55 |

Ann Cowan-Buitenhuis: |

I remember having many conversations with Doug about first and second generations. I mean, this is before things were digitized. So, he used to make a master cassette that would come from the reel-to-reel stuff that he did. And it would be very clean, whereas the reels would not be – I mean, he was a master at fixing things, getting rid of all the ums and ahs and whatever. And so he probably then had a master cassette from which copies would be made, but he would always hold onto the master because every copy was another generation. So that was the way he thought about it.

|

| 41:40 |

Kate Moffat: |

As far as we, and the folks in the SFU archives have been able to determine, we no longer have the original reel to reel for this reading evidence of its existence lies only in evidence of editing hands on the cassette tape, recording. [Start Music: Accordion]

|

| 42:01 |

Kandice Sharren: |

Our interview with Ann and Carolyn, and Michelle’s conversation with Grazia Merla was a reminder that while the archives can provide records and a certain amount of contextual information, particularly when you pay sustained attention to your materials, they cannot capture everything. Ann’s recollection that Images Theater was three quarters full for the reading is information we would never have been able to track down otherwise, as it wasn’t recorded anywhere. Gallant’s fussing over the microphone at her reading in Images Theater is informed by the technical difficulties the day before. And that day before the event downtown uncaptured on audio doesn’t seem to exist in the archive at all, only in fickle human memory.

|

| 42:56 |

Michelle Levy: |

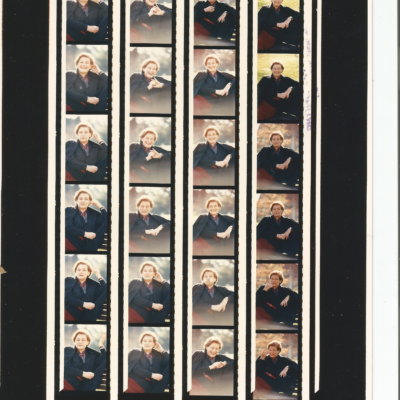

We want to end by connecting our conversations about the reading with the larger paratextual paper record, including the label on the cassette, the poster used to advertise the event, and the proofs Gallant was reading from. In addition to these materials, we were also fortunate to obtain a copy of proofs of photos, taken of Gallant by Bruno Schlumberger on November 1st, 1990, during another visit to Canada. These photos taken near the Rideau canal in Ottawa offer a wonderful glimpse of Gallant, charming, exuberant, but still well-dressed and put together. Kate, Kandice and I were not fortunate enough to have met Gallant or heard her read in person, but with these photos and the recording and our interviews with Ann, Carolyn, and Grazia, yet we are able to conjure a distinct portrait of this most entrancing and provocative writer. [End Music: Accordion]

|

| 44:06 |

Hannah McGregor: |

[Music: Piano Overlaid With Distorted Beat] SpokenWeb is a monthly podcast produced by the SpokenWeb team as part of distributing the audio collected from and created using Canadian literary archival recordings found at universities across Canada. Our producers this month are SpokenWeb contributors, Kate Moffat, Kandice Sharren, and Michelle Levy, with additional audio courtesy of the Simon Fraser University Archives and Records Management Department. Our podcast project manager and supervising producer is Judith Burr. To find out more about SpokeWeb visit spokenweb.ca and subscribe to the SpokenWeb Podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you may listen. If you love us, let us know. Rate us and leave a comment on [SpokenWeb Podcast Theme Music: Instrumental Overlapped With Feminine Vocals] Apple Podcasts or say hi on our social media @SpokenWeb Canada., Stay tuned to your podcast feed later this month for ShortCuts, a brand new take on audio of the month with Katherine McLeod, mini-stories about how literature sounds. |