| 00:18 |

SpokenWeb Podcast Theme Music: |

[Instrumental Overlapped With Feminine Voice] Can you hear me? I don’t know how much projection to do here.

|

| 00:19 |

Hannah McGregor: |

What does literature sound like? What stories will we hear if we listen to the archive? Welcome to the SpokenWeb Podcast: stories about how literature sounds. [End Music: SpokenWeb Podcast Theme Music].

|

| 00:35 |

Hannah McGregor: |

My name is Hannah McGregor, and each month I’ll be bringing you different stories of Canadian literary history, and our contemporary responses to it, created by scholars, poets, students, and artists from across Canada.

|

| 00:49 |

Hannah McGregor: |

There are sounds in the archive, and there are also silences. Here on the podcast, our producers engage closely with what we can hear in archived recordings, but also ask hard questions about the stories behind and around the sounds. When and why was the recording made? Who created this old record, and what story were they trying to tell? How does power function in the archive to uplift some beings and stories, erase others? For everything that we can hear or read in an archive, there are just as many questions about what has not been included, and who has been left out.

|

| 01:29 |

Hannah McGregor: |

The episode we bring you today takes a creative and critical approach to archival records to present a collection of stories about bison, violence, and the history of Canadian conservation. Artist and researcher Michelle Wilson uses archival records to trace what happened to the bison whose descendants ended up on the land now designated as Wood Buffalo National Park in Northern Alberta and in most other conservation herds across Turtle Island. Almost all the plains bison in the North American conservation system are descendants from the herds Michelle investigates in her research. With the help of sound designer, Angus Cruickshank and poet Síle Englert, Wilson brings us a collage of critically interpreted and creatively imagined stories. These stories strive to grapple with the impacts of colonialism and to give voice to the more-than-human characters at the heart of the research. Michelle and her collaborators on this episode are special guests from beyond the SpokenWeb network. Their work builds on conversations we have had on this podcast about critically engaging with archival artifacts, the practice of research creation and audio work as a form of scholarship. In addition to appearing here on the podcast, the sound works in this episode are also part of an exhibition called “GardenShip and State” on display at Museum London until late January, 2022. We are delighted to bring you producer Michelle Wilson with Season 3 Episode 3 [Start Music: SpokenWeb Podcast Theme Music] of the SpokenWeb Podcast: Forced Migration. [End Music: SpokenWeb Podcast Theme Music]

|

| 03:06 |

Michelle Wilson: |

Hi, my name is Michelle Wilson. I’m an artist, mother and researcher.

|

| 03:12 |

Michelle Wilson: |

Back in 2016, I was lucky enough to be invited to do an artist residency at Riding Mountain National Park. I intended to listen to, record, and learn from bison communication and speak to the people who work with them. It was a thrill to find the bison each day and to sit and watch and listen. I learned so much from those who shared their knowledge about these bison, but just as instructive was what was left unsaid about how they came to be corralled for display at a national park. I have been tracing the story of these bison’s ancestors ever since.

|

| 03:50 |

Michelle Wilson: |

The audio artworks I’d like to share with you today come together to tell this story; the forced migration of a lineage of bison. I will take you from so-called Saskatchewan to Manitoba, Kansas and Texas, Montana, then Alberta, and finally to Wood Buffalo National Park, which straddles Alberta and the Northwest Territories. This story spans centuries and zooms in and out from microbes on a blade of grass tickling a bisons nose to national policies.

|

| 04:24 |

Michelle Wilson: |

These short vignettes emerged from a collaboration with poet Síle Englert, who took my 8 to 10-page essays, found their essence, and remixed them into short affective pieces of prose, and Angus Cruickshank, who created layered soundscapes that in a way, bring their own parallel narratives to the pieces. We will hear more from them later.

|

| 04:47 |

Michelle Wilson: |

A note before we listen to these works; I identify as a woman of settler descent, so it was vital for me to tell the story of what settlers did to the bison and their kin. It seemed fitting for me to draw my research from the colonial archive, infuriating as it often was. What I have created here, however, is not a recitation of facts. It is an alternative archive that centers specific and bodied perspectives.

|

| 05:16 |

Michelle Wilson: |

I have found in my research that citing practices did not prevent the transmission of false information and faulty worldviews, so I am taking these stories out of a written tradition. I’m not using the trappings of the academy to give myself authority. My voice as the narrator is never softened by the need to appear objective. On the contrary, it is impassioned and personal. Sometimes I even take on the perspective of a bison. This recentering of the inherited “facts” changes stories of salvation and domination into stories of connection, empathy, and survival.

|

| 05:56 |

Michelle Wilson: |

Our first story takes us to the banks of the north Saskatchewan river in 1873, where the circuitous route to colonial conservation starts.

|

| 06:08 |

Michelle Wilson + Voice Actor: |

[Michelle and a low, gravely voice recite simultaneously] Charles Alloway tried to hold onto a bison bull, to place to anchor them post. But the bull dragged the man, and the rope lacerated his hands, cutting to the bone.

|

| 06:21 |

Michelle Wilson: |

[Start Music: Low-pitched String Instrumental] Until his dying day, Alloway controlled the myth of how he “saved the buffalo.” His story: the white hero, the repentant slaughterer. His words are the ones that survive in the colonial record.

|

| 06:33 |

Michelle Wilson: |

One word – half-breed –tried to obscure the body of the Honourable James McKay, Scottish and Cree, trader and guide with the piercing grey eyes.

|

| 06:45 |

Michelle Wilson: |

Together, McKay and Alloway drove their oxcart down the rutted mud streets and out of Winnipeg to meet a convoy of Métis hunters. Searching for bison to slaughter for hides and pemmican.

|

| 06:56 |

Michelle Wilson: |

A matriarchal band of cows and calves moved through meadows, just emerging from winter’s grip. Grandmothers, aunties, mothers. The bison and must’ve stampeded as the first round of bodies fell. Brown-headed cowbirds took to the sky, their liquid chirps and trills drowned out by hooves and bellows as they abandoned their posts on the bison’s backs.

|

| 07:22 |

Michelle Wilson: |

Encamped at a distance, the women and children heard what they couldn’t see: “a sound deep and moving like a train moving over a bridge… acontinuous deep, steady roar that seems to reach the clouds.”

|

| 07:36 |

Michelle Wilson: |

Close to the carnage, McKay and Alloway felt the guttural calls of anguished mothers resonating in the cavities of their chests. The hunter’s sought cows, their flesh more palatable than the bulls’. Which meant the next generation were in their bellies when they fell.

|

| 07:54 |

Michelle Wilson: |

Women were brought in to butcher and process the bodies. Calves lingered near their fallen mothers, watching.

|

| 08:05 |

Michelle Wilson + Voice Actor: |

[Michelle and a low, gravely voice recite simultaneously] These “pitiful creatures” were run down or lassoed at McKay’s and Alloway’s command. The partners recognized that the current rate of slaughter could not be maintained.

|

| 08:16 |

Michelle Wilson: |

Five freeborn bison calves were captured, survived, and reproduced, forcibly adopted by domestic cows. But their relationship to the land died.

|

| 08:28 |

Michelle Wilson: |

On the establishment of Buffalo National Park, Alloway said:

|

| 08:33 |

Michelle Wilson + Voice Actor: |

[Michelle and a low, gravely voice recite simultaneously] “The animals will increased under natural conditions of peace contentment. Everyone of them came from my original group three heifers and two bulls.”

|

| 08:43 |

Michelle Wilson: |

When the last Canadian bison were being slaughtered in 1878, Alloway sent out a hunter who brought him back 30 bison hides –

|

| 08:52 |

Michelle Wilson + Voice Actor: |

[Michelle and a low, gravely voice recite simultaneously] “We cannot see distant things from the all absorbing present sometimes,”

|

| 08:56 |

Michelle Wilson: |

–he lamented. In trying to anchor the bison bull, Charles Alloway was left with scars on his hands that he carried –

|

| 09:04 |

Michelle Wilson + Voice Actor: |

[Michelle and a low, gravely voice recite simultaneously] –to his grave. [End Music: Low-pitched String Instrumental]

|

| 09:08 |

Angus Cruikshank: |

Hi, my name is Angus Cruikshank. I’m a musician and composer. I’m Michelle’s partner as well. I did the score for “Bedson” and all the other tracks to this project and I also did a bit of editing and some of the mixing.

|

| 09:23 |

Michelle Wilson: |

Hey Angus, thanks so much for talking to us about your process. Can you speak to the track we’re about to hear, “Bedson” and tell us a bit about what the story means to you and how you approached composing a score for it?

|

| 09:38 |

Angus Cruikshank: |

I think “Bedson” is my favourite track because it’s a very –I don’t know – moving story that has so many different parts to it, and it just comes together so well. And so, I think when I approach the track and listen back to Michelle’s performance of the reading, it’s like this very bittersweet tale of the bison and obviously their relationship to Bedson Stoney Mountain, and the plains in general. And so, I didn’t want to necessarily create like a doom and gloom type sound to it or composition to it, I wanted there to be almost like a pensive reflective type sound where you’re – it is kind of in a minor chord but there are like major chords in it that maybe convey some sort of, not hope but empathy to the story?

|

| 10:39 |

Michelle Wilson: |

I do like how you haven’t made it just a simple minor score because there are moments of lightheartedness in this piece and so I was wondering if you could talk to us about what you were doing with those upper register notes.

|

| 10:54 |

Angus Cruikshank: |

Upper register notes that are just really kind of holding down a beat and so it kind of gives this it – it kind of gives the piece sort of like a galloping feel to it, which I guess you know you could link back to maybe the bison, but also just sort of this running feel. Its like a [Sings] “duhn duhn dat dat dat dat dat”. So I don’t know I just it felt really right and it felt like it really worked for the mood and the theme of the piece.

|

| 11:25 |

Michelle Wilson: |

What do you see as the themes in “Bedson” and how did that influence the kind of sonic imagery you came up with?

|

| 11:32 |

Angus Cruikshank: |

I think the theme of the song “Bedson” is one of incarceration and the penitentiary, the structure that still exists today and is still a penitentiary and one of the oldest in Canada if not the oldest. I think a lot of people aren’t aware of that and how it played a role in essentially isolating, confining people who resisted colonization. And kind of the isolation of the penitentiary itself within this vastness. And having lived out there, and sort of seen vastness, that isolation of winter in the prairies, it’s sort of a very beautiful yet morose vibe, because nothing can really survive out there, yet the sun is shining and its 40 below. Yeah, nothing except bison can survive out there and it’s beautiful. And I think it worked really well with, when I picture Stoney Mountain Penitentiary just sort of sitting there alone, or when you listen to it you sort of maybe hear that maybe hopelessness, but maybe frustration, but also like an empathy towards those who are incarcerated there, both human and nonhuman such as the bison. I think musically it works so well, and I think why it is my favourite is because it really captures that vastness I was talking about, the use of delay it’s really just like kind of two chords, and then yeah then a slight variation as the song progresses.

|

| 13:23 |

Michelle Wilson: |

Okay Angus, one last question. We’ve collaborated together for a very long time. I was wondering if you could tell me a bit about what it’s like to collaborate by layering on someone else’s words?

|

| 13:38 |

Angus Cruikshank: |

You’re really interpreting and trying to compliment what is being said, and that can be kind of hard sometimes because the music is there to support the story. You have a lot of leeway, but at the same time it’s really hard to capture the essence of what is being said and it does take time to kind of get that right feeling. Because if you don’t have it then it could distract from the actual story itself, and that is really the most important part.

|

| 14:13 |

Michelle Wilson: |

Well thanks so much Angus, I really do think that you bring life and texture to these pieces and a lot of the empathy that people perceive in them comes from your compositions so thank you, and here is “Bedson”. [Start Music: “Bedson” by Angus Cruikshank] It is a testament to how remarkable the sight of bison were, that in 1880, 800 people attended the auction that determined the fate of just 13. Because the bison were once so plentiful here that at a distance, they could have been mistaken for a churning, brownish-black river surging across the plain. The winner of the auction was Samuel L. Bedson, the warden of Stony Mountain Penitentiary. In the early hours of a frigid morning, a tawny bison calf was born onto trembling legs. Still wet with afterbirth, he had barely taken his first tentative steps when his herd, now 14 in number, was roused from slumber by men sent to drive them to their new home.

|

| 15:22 |

Michelle Wilson: |

Imagine the wind whipping across a sea of flat, uniform ground on a painfully bright February day. On top of a sudden swell in the land sits a three-story sandy brick building. Dozens of elegant arched windows peer down upon you, the bars not discernable from a distance—that’s what those 14 bison saw. The bison were often corralled in a stone pen near the farm on the prison grounds. This complex was nicknamed “the castle,” and Bedson was its king. He was no great hunter; he was a collector, always trying to domesticate wild animals for the amusement of his family and neighbours. The farm at Stony Mountain housed a collection of wolves, deer, bears, and badgers, but Bedson’s moose were local favourites; a pair had even been trained to pull a handsome sled in the winter.

|

| 16:17 |

Michelle Wilson: |

On a Christmas afternoon, Bedson tried a similar trick with a two-year-old bison bull. His shaggy brown body was hitched to a toboggan. Eight merry makers loaded on the sled while five or six of the incarcerated men held onto a rope tied around the bison’s neck. Imagine this ludicrous game of inter-species tug-of-war, the free laughing and playing while the prisoners, human and bison, were scared for their lives. A tense calm lasted for about 15 or 20 minutes until suddenly the bull leapt into the air, scattering prisoners and guests into the snow. There was no catching the bull once he had gained his freedom. Months later, Bedson received a letter from North Dakota that a lone young bull had been found grazing with an old rope tied around his neck. Bedson sent a hired man across the border to bring his property back. [End Music: “Bedson” by Angus Cruikshank]

|

| 17:32 |

Síle Englert: |

My name is Síle Englert. I am a writer, editor, and visual artist, and I feel very grateful to be a small part of this project, in that it was my work to edit in a sort of cut and paste way, like a collage, to take these longer pieces describing the history of the bison and rework them into shorter narratives to be recorded, like storytelling.

|

| 17:55 |

Michelle Wilson: |

Síle, could you tell us a bit about the story you most enjoyed working on?

|

| 18:00 |

Síle Englert: |

“Fight or Flight”, I think is the piece that probably affected me and stayed with me the most. Maybe, because you’ve written it in a first-person perspective from the mind of one of the bison and that means you brought an immediacy to the history. It changed the language you were able to use to describe the experience, allowing human emotions and familial relationships so that the listener completely empathizes with the bison’s and experience. I think the shift to a first-person perspective makes the process of creating this piece, step-by-step even more interesting too. You’ve done an incredible amount of research, collecting historical accounts, stories, and statistics. And collected, the picture that all of this information paints is sad and disturbing, evocative of the horrors and the pointless suffering that humans put these animals through. But in “Fight or Flight” in particular, we hear the story from one of the bison herself. And it’s a sort of magic, I think, to take this pile of numbers and information and create a first person account of some of these moments where you can feel the pain of it right in your chest.

|

| 19:30 |

Síle Englert: |

And then you sent the longer story to me and my part I think was another kind of archaeological process: digging through this wealth of matter to find pieces that felt like the essence of the story. And then figuring out how those pieces fit together as a narrative. And there’s there’s an emotional element to the process too. When so much damage was done to both these bison and to the environment that we share, when so much pain was caused, how do you decide what’s most important? What people should hear? I had to make sure I kept enough of the spirit and the experience of the bison as you wrote it, and enough of the horror so that those listening could understand what these creatures went through – and to maintain that organic flow that’s kind of difficult to describe in words that movement you can hear in the story. All of that comes through in the final step, in the recording you’ve done, the sound and the music, these bison, this particular bison comes to life –her wants and needs and experience and pain. I think several steps of distilling this down to its essence from history, to story, from information, to emotion allows those listening to connect with something real, something far beyond numbers and statistics.

|

| 21:12 |

Michelle Wilson: |

Thank you so much Síle for that generous and thoughtful reflection. And now here is “Fight or Flight”.

|

| 21:22 |

Michelle Wilson: |

[Start Music: Low-pitched String Instrumental] [Michelle performing ‘Flight or Flight”] We are grazing, hidden in the breaks between sand hills. Always alert, our ears panning for the sounds of men. My body orients toward the wind, waiting for the odour that twangs my fraught nerves and triggers our flight. I don’t want to leave this place. The snow has just melted from the slopes, moistening the thirsty earth below, reviving the scrubby grass after a long winter. There are so few of us, now. So few babies. We cannot let down our guard to breed as we used to. Two lame bulls follow us but they barely have the energy to register when we are in estrus. When we do conceive, our bodies can no longer nourish the unborn. We are haunted by those stolen from us. Mothers who aren’t killed fighting off the snatchers return again and again to the site of their loss. As the night lifts, my body is alive with sensation— rain drizzles, a sweet, pungent balm rises from the earth. I don’t detect them until they are among us. We bolt toward the wind. We cannot stop moving. We might still outrun them. The bulls cannot keep up and drift away, but these predators are not enticed by weakness. Night settles again and they keep pressing us. The sun rises and they are still there. Three nights and days they keep at our heels. Urine, sweat, and dead skin wafts toward me on a breeze exhaled from a canyon mouth. I turn, lead my sisters and their young onto an open prairie. My instincts have betrayed me, betrayed us. I hear the oscillating whistle of a lasso and the desperate, grunting cry of a calf. I hear him fall. A thud, thud, thud, dragging and scraping. The man’s rope finds another of our young and pulls him down. But now we know what he is here for. My sister is a blur of bristled hair as she charges him. There is a crack of thunder, and mushrooming from the deafening sound is the acrid, smoky, rotting smell of water that cannot breathe. My sister staggers a few strides from the source of her pain and sinks to the earth. Disoriented by the sound and smell of death, I barely register the hum of the rope when it strikes out and brings down our last baby. [End Music: Low-pitched String Instrumental]

|

| 24:14 |

Michelle Wilson: |

This next story runs parallel to the one you just heard. “Fight or Flight” and this story “How Buffalo Jones Got His Name” were created from autobiographies of a man named Buffalo Jones. “Fight or Flight” uses his observations to understand the beings he prayed on, while “How Buffalo Jones Got His Name” confronts the attitudes used to justify the hunt.

|

| 24:41 |

Michelle Wilson: |

[Start Music: Piano and String Instrumental] [Michelle performing “How Buffalo Jones Got His Name”] Some people would have you believe that Charles Jesse ‘Buffalo’ Jones got his nickname for his conservation efforts. Please don’t believe them. Jones heard God’s call in Genesis 1:26 –.

|

| 24:54 |

Voice Actor: |

[Church Choir Singers Underlaid] “Let Us make man in Our image, after Our likeness; and let them have dominion over all the earth and over everything that creepeth upon the earth.”

|

| 25:17 |

Michelle Wilson: |

[Michelle performing “How Buffalo Jones Got His Name”] – He set out to capture the last remaining remnants of the great southern bison herd, not as some noble conservation effort, but as breeding stock for his own grand experiment. On the first three expeditions, he took only calves. He learned as he went, and the bison he encountered suffered for his mistakes. The calves refused buckets of water and called relentlessly for their mothers. Jones and his men rode out, looking for range cows to forcibly milk, but instead found two of the bison mothers wandering the site of their loss. Jones shot one of them for her meat and milked her dead body. When calves became rare, he resolved not to leave any bison on the plain. Capture myopathy was not identified until 1964, diagnosed in another endangered species. The stress of being captured triggers the creature’s biological defense mechanisms, and the prolonged or intense engagement of these mechanisms causes massive, often fatal system failure. The animal suffers lethargy, muscle weakness, incoordination, rapid breathing, shivering, dark red urine, and hypothermia. Their blood turns to acid. Their muscles suffer necrosis and die as the animal is still struggling for life. This is how the last of the Southern bison died. Jones believed that there was no place for wild bison on their former ranges. Man’s mastery transformed these arid tracts into productive farms “made exceptionally fertile by the manure, bones, and flesh of the millions which lived and died there during centuries past.” With a name like Buffalo Jones, it would be easy to believe that he saved the bison. [End Music: Piano and Strings Instrumental]

|

| 27:35 |

Michelle Wilson: |

After Buffalo Jones’ bison schemes went bust, he sold his herd, a mix of bison from the Southern Plains and decedents of the Saskatchewan calves, to two ranchers at the Flathead Reservation in Montana. These two ranchers, Michael Pablo and Charles Allard were adding to their captive herd. But how had these bison come to be protected within the Flathead Valley? Tracking down this history was, for me, a journey through a twisted game of racist telephone. It was really fascinating, in the way that a disaster is fascinating, to see how white authors used quotes and citations in articles and dissertations to give legitimacy to each garbled version of the past. I followed this path until at last, I arrived at a telling shared by the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation. In the show notes, we’ve linked to a video produced by the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes about the return of the bison and their fight to continue their stewardship and sovereignty over their lands. You will hear the following two stories back-to-back, they share how the bison came to be on the land, and how they were forced from it.

|

| 28:53 |

Michelle Wilson: |

The search for facts goes in circles. I find a fact and follow it back to its source, only to find every new telling contaminated. [Start Music: Intermittent Percussion, Tonal Sounds] Who first brought the bison back to the Flathead Reservation? A white trader named Charles Aubrey inserted himself into history by recording his story.

|

| 29:12 |

Michelle Wilson: |

[Reading Charles Aubrey’s words] In the year 1877, I was located at the Marias River and engaged in the Indian trade…Among the Pend d’Oreille Indians… from across the mountains, was (a)… man… whose Christian name was Sam. He was known to the Blackfeet as Short Coyote… A rather comely girl had attracted the attention of Sam… (and) she became his wife. I told him very frankly that he had made a mistake…I said to him; “You are a strong Catholic and your Church does not permit polygamous marriages” He feared he would be punished by the fathers of St. Ignatius Mission…I thought there was still a chance to make peace with the soldier band of his tribe by getting a pardon from the fathers… I then suggested…he rope some buffalo calves…and then give them as a peace offering to the fathers at the mission. Sam herded his buffalo with the milk stock for five days, resting and making arrangements for his trip across the mountains… seven head in all is my recollection of the bunch… I afterward learned… that immediately upon his arrival upon the reservation he was arrested and severely flogged… In the course of time I heard of Sam’s death…passing away peacefully in his lodge…

|

| 30:24 |

Michelle Wilson: |

Other tellings of Sam’s story seep into my consciousness as I wade deeper into newspapers and websites. Racism oozing between every word. They describe Walking Coyote’s meeting with Charles Allard and Michel Pablo, who bought the bison calves. They speak of him “brooding… over gleaming piles of wealth.” They record his death as “a less-than-heroic exit” under a Missoula bridge, resulting from “a drinking spree,” and “one that matched the spirit in which he had lived and captured the calves that were now prospering on the rich grasslands of the Flathead.” The words sit like bile in my mouth. Walking Coyote’s legacy as a drunk, greedy Indian became entrenched in the dominant archive. I wonder if the tendrils of Aubrey’s story have made their way into others. Did interviewers seek out those that would corroborate their stories? Or did the keepers of more profound knowledge withhold it, for fear of contamination? In 1978, when he was 87 years old, Pend d’Oreille Elder and historian Mose Chouteh recorded the story of how bison returned to the Flathead reservation. I will let Mose Chouteh’s words speak for themselves:

|

| 31:40 |

Michelle Wilson, reciting Mose Chouteh: |

[Reading Mose Chouteh’s words] While I was growing up I heard this told by many elders…It is about a man called Ataticeʔ. (While on a hunt several buffalo followed their camp) And so in the evening, (the men) went into the tipi. The chiefs were smoking… Ataticeʔ said, “Hello. I have come to ask you, my chiefs. I think that it would be good if we took these buffalo back to our land to live there.” Some of the chiefs said, “that’s exactly right.” And some chiefs said… if we take them back to our land, we will be tied down… We will not be able to go anywhere. We will just be in one place as we gather our food.” The chiefs disagreed with each other. Half of them said yes and the other half said no. (After three days the council remained at an impasse and out of respect for the tribal need for consensus on major decisions Ataticeʔ withdrew his proposal). As he mounted his horse… He waved at these buffalo, like sending them to different parts of the prairies. Ataticeʔ said to the buffalo… “it will be up to each of us whatever happens to you and whatever happens to me. That is all.” And all these buffalo turned towards the east, the rising sun… They were going away. And Ataticeʔ cried. Ataticeʔ’s son Ɫatatí having the same deep connection to the buffalo as his father, renewed his father’s request to capture calves in the 1870s. The council, seeing the effects of the unchecked settler slaughter of the buffalo, approved Ɫatatí’s plan. Six calves were brought over the mountain range, they soon flourished and became twelve. Ɫatatí’s mother, meanwhile, remarried Samwel Walking Coyote. While Ɫatatí was away, two people went to see Samwel. One was called Charles Allard, and the other man was called Michel Pablo. These two men met with him and told Samwel, “we’ve come to buy your buffalo.” Samwel said, “ok, it will be so…” Ɫatatí returned to his house… all the buffalo were gone… he asked his mother, “where are my buffalo?” And his mother told him, “your stepfather sold them.” And Ɫatatí cried. [End Music: Intermittent Percussion, Tonal Sounds]

|

| 34:07 |

Michelle Wilson: |

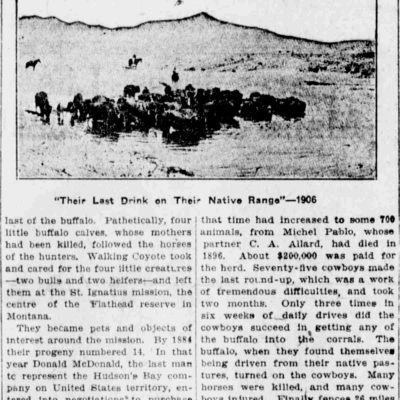

Michel Pablo’s bison were sold to the Canadian government in 1907. [Start Music: Xylophone Instrumental] Extraction from the land was violent and rail travel for bison was perilous. I wonder if the removal triggered memories of their previous transfer from Kansas to Montana. The only recorded death during that transfer of bison was a calf who was trampled to death in the stifling, shifting, rattling cars. In my imagination, the calf is still a reddish caramel colour. She is not yet weaned. Was she with her mother? Had her mother been born into captivity or was she dragged by lasso from her own mother’s side? I know that somewhere in her matrilineal line, a cow fought a man to keep her calf and probably died in the process. Did this trampled calf carry that memory in her bones? Did her mother listen to the imperatives of her instincts and keep her calf close? Did her own feet bring her calf’s death? The egg that became my daughter existed in my genetic code when I was an egg inside my mother. What of my mother’s trauma is playing out in my daughter’s body? How does this kind of trauma make its way into genetic material? They say a butterfly has sense memories carried over from its caterpillar self, even though it basically becomes a gooey soup of cells in the chrysalis. I imagine the phantom call of a calf falling under shifting panicked feet, echoing in the body of another cow who died shortly after being loaded onto a wagon train on the Flathead Reservation. Cowboys loaded her into a reinforced wagon without her calf. The calf grunted and called to his mother. The call of her offspring drove her into a frenzy. In desperation she rammed her horns through the two inches of wood that imprisoned her. Her horns became lodged in the wood and in thrashing against it she broke her own neck. She was butchered, and her hide sold. I don’t know what happened to her calf. I know that 19 other bison died in the round up. 708 were shipped off the Flathead Reservation.653 made it to the ill-fated Buffalo National Park. 55 stayed at Elk Island National Park and founded a herd there. The colonial story of bison conservation is one of rescue. The Confederated Salish And Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation, and many other signatories of the Buffalo Treaty, are writing a new and yet ancient story. It is theirs to tell. It is incumbent on us to find it. [End Music: Xylophone Instrumental]

|

| 37:11 |

Michelle Wilson: |

We now arrive at Buffalo National Park near Wainwright, Alberta. The archival information around this now-defunct park demonstrates an absolute indifference to the agency of other beings and to the specificity of this place. The result was an ecological and economic disaster. In this piece, I tried to speak with two voices, one that personifies the Parks service’s approach to resource management and another that takes the lives of bison and their kin seriously.

|

| 37:47 |

Michelle Wilson: |

Numbers. [Start Music: Atmospheric Instrumental] They transmogrified breathing, eating, shitting, connected bison into numbers. That’s what happens when a being becomes a commodity –

|

| 37:57 |

Michelle Wilson + Voice Actor: |

[Michelle and a deep voice recite simultaneously] 20 to 60 million bison ranged North America before colonial contact.

|

| 38:03 |

Michelle Wilson: |

–Surveyors and homestead inspectors came looking for a home for the government’s newly acquired bison. What they saw was land that had no value because it could not be settled or farmed. It was worthless, but maybe it could be made useful. This place, southwest of Wainwright, Alberta, became Buffalo National Park in 1908. Reducing the bison’s lives to numbers –

|

| 38:29 |

Michelle Wilson + Voice Actor: |

[Michelle and a deep voice recite simultaneously] In 1888 there were 103 wild plains bison in North America.

|

| 40:13 |

Michelle Wilson: |

–The land and the bison had sustained one another. The bison compacted the arid ground, helping it hold on to precious moisture. Cows and bulls felt their way across the grassland, stems and blades tickling their nostrils as soil stirred up by a roving muzzle and probing tongue was inhaled –

|

| 40:20 |

Michelle Wilson + Voice Actor: |

[Michelle and a deep voice recite simultaneously] By 1912, 748 bison had arrived at Buffalo National Park from Michel Pablo’s herd.

|

| 40:20 |

Michelle Wilson: |

–There was an intimate interconnection between bison and the thousands of “microbes; fungi, bacteria, and protozoa” populating each square centimetre of forage. These microscopic beings had the enzymes to break down cellulose in the grasses the bison eats. Neither being could live without this symbiotic relationship –

|

| 40:20 |

Michelle Wilson + Voice Actor: |

[Michelle and a deep voice recite simultaneously] The government wanted quick and exponential growth. By 1922, 6,780 bison were sharing the park’s limited resources with large deer, moose, and elk populations. The land strained under the pressure of all these mouths and bodies.

|

| 40:20 |

Michelle Wilson: |

–Reciprocity and movement had co-evolved over centuries, enabling the dunes and desert-like conditions of the Hills to sustain vast herds over the winter months –

|

| 40:20 |

Michelle Wilson + Voice Actor: |

[Michelle and a deep voice recite simultaneously] Over 19,141 bison were slaughtered over the park’s thirty-year existence.With Canada’s involvement in World War II looming, the park was declared a failure. On December 30, 1939, the last bison were shot; untold numbers of deer, moose, and elk followed them to the abattoir. [End Music: Atmospheric Instrumental]

|

| 40:20 |

Michelle Wilson: |

– Just numbers.

|

| 40:23 |

Michelle Wilson: |

We have been on a journey through space and time. In this final piece, we arrive at Wood Buffalo National Park in the year 2021. I wrote this closing section in response to an article by Chloe Dragon Smith and Robert Grandjambe in Briarpatch magazine. We’ve linked it in the show notes as well. Chloe and Robert live off the land within their ancestral territory, which falls within the bounds of Wood Buffalo. Their article is a missive from the future to their future children. It references an imagined fulsome and personal apology delivered by Parks Canada to the 11 Indigenous nations and councils whose traditional territories the sprawling Wood Buffalo occupies. In this section, I used the archival information around Wood Buffalo to imagine what that apology would need to atone for. This apology felt like the only way to address the ongoing violations at Wood Buffalo, but also not nearly enough. So, for me, it is simply a place to start.

|

| 41:38 |

Michelle Wilson: |

[Start Music: Reverberating Tonal Sound ] I want to speak to you today about what we did— our predecessors— the many branches of the Dominion government and the people who ran them; the treaty negotiators, the Department of the Interior, and Parks Canada. The creation of Wood Buffalo National Park was an act of “ecological imperialism.” From its first inception, the Park was designed to be a place that excluded Indigenous peoples, a place where Canada could extinguish treaty rights. We created a swath of Land where vital relationships between human and non-human have been severed. We saw the bison as an exploitable resource and used their bodies to make money. Our park wardens slaughtered bison one day and persecuted your hunters the next. We turned exercising your rights and sovereignty into a privilege. We used racial dogmas to determine who had hereditary rights within the Park, and we used a politics of purity to drive communities apart. We separated families. We ignored letters pleading to be reunited. We contributed to the residential school system and intentionally engendered dependency instead of acknowledging your right to hunt and practice lifeways on your own lands. We chose to believe that pulling the strand of bison from this web wouldn’t cause it to unravel. We armed police and then wardens to arrest and harass your guardians. We created a policy of surveillance and intimidation. Even when we built abattoirs and killed hundreds a year, still we kept you from the bison. Our attachment to conceptual borders extends to policing the boundaries between Wood Bison and Plains Bison, between pure and hybrid, between contaminated and uncontaminated. Steeped in white supremacy, we did not see how these logics of purity were weaponized against both bison and your people. These imagined borders place bison and Indigenous peoples outside the protective bounds of white and human. This pattern has continued. Our pools of knowledge are shallow, and our spatial and temporal scales are different than yours. Your pools of knowledge are deep and dependent on a connection to place and language. We have come to embrace the term “two-eyed seeing,” as envisaged by Mi’kmaw Elder Dr. Albert Marshall. It is a concept of “learning to see from one eye with the strengths of Indigenous knowledges and ways of knowing, and from the other eye with the strengths of mainstream knowledges and ways of knowing, and to use both these eyes together for the benefit of all.” But first, we acknowledge that for nearly a century our laws stripped Indigenous peoples of their treaty rights if they pursued a university education. We tried to outlaw “two-eyed seeing”. We are ashamed that we fought for nearly a century to avoid fulfilling our Treaty commitments to your Nations. We apologize to you. We apologize for making your communities fight for what was theirs. We would like to work with you, the descendants of the dispossessed, to make restitution for these wrongs. To move beyond access and towards true sovereignty on the Land. We recognize that decolonization is not a metaphor. [End Music: Reverberating Tonal Sound]

|

| 45:37 |

Michelle Wilson: |

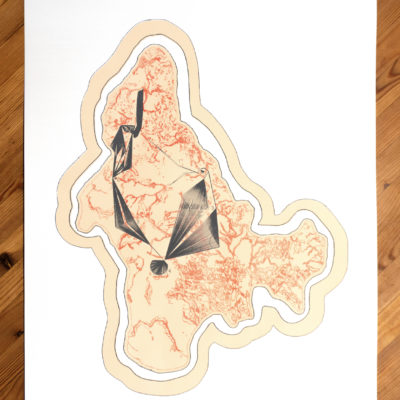

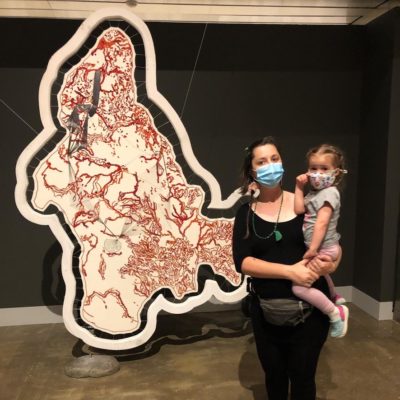

Thank you so much for coming with me on this journey. The audio pieces I have shared with you today have many lives. They can also be experienced as part of an interactive textile map. It will be on view as part of the “GardenShip and State” exhibition at Museum London, in London, Ontario. We will link to the exhibition and documentation of the piece in the show notes as well. I hope that this collection of stories has illuminated how bison conservation has been a tool of colonization. The sources I have drawn from want us to believe conservation stories are ones of rescue, but as Indigenous literature scholar Pauline Wakeham puts it, conservation narratives attempt “to overwrite colonial violence” and locate it in a distant past. If you are interested in a future where a decolonized relationship with bison exists, please check out the work being done by Dr. Leroy Little Bear, The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation, and many other signatories of the Buffalo Treaty. We’ve linked to an excellent site that documents the work of the Buffalo Treaty to get you started on this journey

|

| 46:57 |

Hannah McGregor: |

[Start Music: SpokenWeb Podcast Theme Music] SpokenWeb is a monthly podcast produced by the SpokenWeb team as part of distributing the audio collected from (and created using) Canadian Literary archival recordings found at universities across Canada. Our producer this month is Michelle Wilson. The audio artworks featured in this episode were originally created as part of Michelle’s interactive textile map, “Forced Migration”. It’s on view at Museum London as part of the “GardenShip and State” exhibition until January 23rd, 2020. See the links in the show notes and the image gallery on our episode webpage to engage more deeply with the research and stories behind this episode. Our podcast project manager and supervising producer is Judith Burr and our episodes are transcribed by Kelly Cubbon. To find out more about SpokenWeb visit spokenweb.ca and subscribe to the SpokenWeb Podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you may listen. If you love us, let us know, rate us, and leave a comment on Apple Podcasts or say hi on our social media @SpokenWebCanada. Stay tuned to your podcast feed later this month for ShortCuts with Katherine McLeod, mini stories about how literature sounds. [End Music: SpokenWeb Podcast Theme Music] |