| (00:04) |

SpokenWeb Podcast Theme Music: |

[Instrumental Overlapped With Feminine Voice] Can you hear me? I don’t know how much projection to do here. |

| (00:19) |

Katherine McLeod |

[Music fades] What does literature sound like? What stories will we hear if we listen to the archive? Welcome to the Spoken Web podcast, stories about how literature sounds. [Music ends]

My name is Katherine McLeod, and each month I’ll be bringing you different stories of Canadian literary history and our contemporary responses to it created by scholars, poets, students, and artists from across Canada. Imagine sitting down to read a book for your literature class. When I said that, you probably pictured yourself opening a book, maybe a Toni Morrison novel, or a poetry anthology. But what if reading a book for your class looked like putting on headphones and pressing play? What happens if we consider the audio book pedagogically? What does the medium of the audiobook allow for in the classroom? How do students respond to listening to books?

In this episode, styled like an audio essay, producers Dr. Michelle Levy and MA student Maya Schwartz ask these very questions, putting current scholarship and personal reflection in conversation with interviews with professors and students alike in order to think through how literature sounds when it comes to audiobooks. Put on those headphones and turn up those speakers. Here is episode 7 of season 4 of the SpokenWeb Podcast: Audiobooks in the Classroom. [SpokenWeb Podcast Theme Music begins to play and quickly fades] |

| (02:01) |

Voices Overlapping |

It’s like, listen, ear skimming-

You kind of just like-

Blank Out listening-

Is attention by treating-

-artifact myself-

-Oh, this is like maybe a quarter of the way through the books, so it must be a quarter of—–

The way the author enters the room. And I often, uh, when I’m teaching… |

| (02:17) |

AI Generated Voice |

You’re listening to “Audiobooks in the Classroom” by Michelle Levy, narrated by Michelle Levy and Maya Schwartz. |

| (02:28) |

Michelle |

This podcast asks a seemingly simple question; how are we harnessing new audio forms to teach literature in the university classroom? According to Casey Harrison writing in 2011, “there is a dearth of scholarly literature on the medium of the audiobook.”

From this, she concludes that this widely popular form is not being taken seriously by the academic establishment. With some important exceptions, the lack of research on the audiobook persists, even though as Harrison writes, “academics and avid readers happily avow their enjoyment and appreciation of recorded books.”

[Light electronic music begins to play]

As you will hear throughout this episode, we are getting a lot of dishes washed with all of our listening. But are we taking advantage of the pedagogical potential of literary audio? This episode addresses the challenges both real and imagined that are shaping both the use of and the resistance to the incorporation of literary audio in teaching. [Electronic music ends]

It explores some of the ways in which college instructors are taking advantage of the wealth of literary audio now available to us.

It also offers reflections from students about how they are experiencing these experiments with literary audio. Ultimately, this episode of the SpokenWeb Podcast seeks to offer some practical guidance to instructors and to elucidate how the use of literary audio can enhance connection, understanding, and enjoyment for our students. [Quiet string music begins to play]

To address these issues from the perspective of both the instructor and the student.

This podcast will interweave my own commentary with that of Professor Jentery Sayers of the University of Victoria, an expert in sound media and literary history, who Maya interviewed for this podcast. You will also hear an interview conducted with four graduate students from Concordia University who have recently taken a course with Professor Jason Camlot, that centered audio literature PhD students, Ghislaine Comeau and Andy Perluzzo, and MA students Ella Jando-Saul and Maia Harris were asked to set up questions similar to the ones I asked Jentery, and I’m delighted to include their responses to provide a range of student perspectives on the use of audio literature.

I’m also joined by Maya Schwartz, an MA student at SFU, who helped to produce this podcast episode and who joins me in voicing some of the narrative commentary in this episode. [String music ends]

As an avid listener of literary audiobooks and podcasts for over a decade, it was the pandemic that finally prompted me to teach audiobooks. Jentery had decided to take the plunge before Covid. |

| (05:07) |

Jentery |

If I recall correctly, I think I proposed it prior to the shift online for the pandemic. We shifted in March, 2020. But what I did as I was preparing it is I took advantage of some aspects of that dynamic. The fact that, I think, increasingly people were listening to podcasts, people were listening to literature, and, you know, a lot of people were inside for [Jentery laughs] doing a lot of their work.

So I taught, I ended up teaching the seminar online, and doing what I can or doing what I could to integrate audio into the teaching, into the dynamic that way. And I think on the whole, it worked out quite well. It was a joy to teach. |

| (05:45) |

Michelle |

[Low string music begins to play]

As Jentery says, the shift to online teaching during the pandemic meant that students were receiving their instruction through audio and video, and apart from others in their home, which seemed to support the incorporation of literary audio into our courses. When teaching audiobooks and literary audio as instructors, we face a number of practical considerations.

Should we require students to buy both the audiobook and a print copy of the book? Assuming the audiobook is not freely available, will they need a print copy of the book for their assignments? And if we require them to purchase both, can we justify the cost, particularly given that audible.ca unaccountably fails to offer a student membership? Could we assume that every student had a device from which they could access an audiobook or a podcast?

There were also questions about which audiobook or podcast to select and how much performance and accessibility should drive our selection. In some cases, such as canonical novels like those by Charles Dickens or Jane Austen, there may be dozens of audiobook versions to choose from, and much like the decision about which print edition to ask our students to purchase, selecting an audiobook requires thoughtful deliberation of the various options. Accessibility also plays a role. Most of our students have spent their academic careers silently reading. How do we prepare them to listen? [String music ends]

One of the audiobooks I have assigned, Anna Burns’ novel Milkman, is narrated by a character known only as “middle sister”. It is performed by Belfast actor Brid Brennan in a thick northern Irish accent. For me, the voicing brought the novel vividly to life. It also helped me to make sense of the stream of consciousness narration and the disorientation that comes from none of the characters being assigned proper names. [Quiet electronic music begins to play]

But some of my students struggled to hear the words and the story through the accent. Thus, a feature of the voicing that enhanced the story for me was a barrier to some. I begin, however, with one of the most fundamental questions that has vexed the use of audiobooks for teaching and research; whether listening is reading. |

| (08:01) |

AI Generated Voice |

Chapter One: Is listening reading? [Electronic music ends] |

| (08:07) |

Michelle |

There is an entrenched suspicion that listening to an audiobook or a podcast is a passive activity, and hence not really reading. Jentery describes how this issue arose in a contemporary American fiction class he taught about a decade ago. One of his students kept referencing, having listened to a novel assigned for the course. |

| (08:28) |

Jentery |

There was one student in particular that talked about listening the whole time when answering questions and just having class discussion. And I was fascinated by this. So I just said, do you mean just to be honest, do you mean this literally? Are you, are you listening to the book? Are you using this as a way to talk about the novel as a living text, as language, as discourse? And he’s like, no, no, I’ve listened to audiobook versions. And then, and he is like, is that okay?

And so it became this discussion around the popular student perception, I think, that listening was cheating, right? And so I was like, oh, this is, this is a fascinating topic, but also more important, like it is not, and I want to think through why, for a number of reasons, including accessibility, we might want to, for good reason, debunk the that listening is cheating or that books are not meant to be listened to. |

| (09:19) |

Michelle |

In our conversation, this question of whether listening is reading and more pointedly and judgmentally, whether listening is cheating, resonated with Jentery who began to think about how these ingrained biases impacted his scholarly approach to and valuation of literary audio. |

| (09:38) |

Jentery |

I’ve always been interested in the kind of cultural dimensions of listening, the cultural dimensions of sound, but only recently, like in the last eight years or so, started to think about that in literature. And I think partly because I too had inherited this idea that if I started to do that work in literary studies, I’d be cheating my discipline.

So it kind of brushed against the grain of how I had been taught literary studies, how to read text with a capital T as a methodological field, but also, yeah, just plainly the sensory work I was doing and why I was parsing it. Like why was it that when I was listening I was like, oh, this is my media studies work. And why when I was reading, I was like, oh, this is media studies and or literary studies depending on the content. |

| (10:16) |

Michelle |

[Quiet string music begins to play]

In his introduction to the essay collection, Audiobooks, Literature and Sound Studies, Matthew Rubery, an historian of talking books, examines some of the assumptions that feed into assertions that listening as opposed to reading on the page, offers a compromised cognitive experience. According to Rubery, there is a belief that audiobooks do not require the same level of concentration as printed books, or that one can be inattentive while listening to an audiobook. He explains how the very features promoted by audiobook vendors as selling points; their convenience, portability, and supplementary status to other activities are the same ones used by critics to denigrate the format as a diluted version of the printed book.

Audiobooks are chiefly marketed as or conceived to be entertainment, and this is another reason why they’re considered derivative of or subordinate to the printed book. What, however, other than marketing pitches underlies the belief that listening to audiobooks is not the same as reading, and why is it considered even more punitively a form of cheating?

One possibility relates to what is called, and this is a quotation from Rubery, “the reader’s vocalization of the printed page, which has been taken by many to be a fundamental part of the imaginative apprehension of literature. When we read on the page, it is thought that we voice what we are reading in our head, and thus are more actively involved in meaning making than when a text is read to us.” The implication again is one of listening being passive, that instead of voicing in our minds, we are merely receptors when we listen.

[String music ends]

A similar objection is often made to watching a film version of a book before reading the book. The belief, again, is that it robs us of our imaginative reconstruction of the world the author creates through words alone. Reading on the page, so the theory goes, demands one’s undivided attention and imaginative powers, whereas listening does not because it allows and even invites us to perform other activities. And the fact is that many of us do turn to audiobooks in the hopes that we can accomplish other tasks while listening, but what in fact happens when we listen in order to or because we think we can multitask? |

| (12:43) |

AI Generated Voice |

Chapter two: Listening As Overwork |

| (12:49) |

Maya |

As you will hear in the conversations throughout this podcast, many of us turn to audiobooks and podcasts as an attempt to maximize productivity, to fill intellectually the downtime of commuting or driving across the country, of doing chores or other forms of physical labor. Here is Jentery speaking about why he began to listen. |

| (13:09) |

Jentery |

And at first I took this as just basically a way of multitasking. Maybe it was like a form of overwork. If I’m being more reflective about it, I’m like, okay, so I might be going for a walk or I might be gardening or I might be doing the dishes, so I’m gonna put on a podcast that’s about, you know, literary criticism, literary culture or games culture, or I might listen to an audio book. |

| (13:29) |

Maya |

Maia, an MA student from Concordia similarly explained that her desire to listen while doing other things was a coping mechanism meant to address overwork. |

| (13:39) |

Maia |

I also have a similar experience. It was during my undergrad and I was really overworked, so I thought I’d get, I think it’s called scribd, an account on there. And I downloaded Milton’s Paradise Lost and I thought, this is great, I can do this while I work out. Two birds, one stone, and I, I think I missed about half the novel that way and it was a really unpleasant time. |

| (14:00) |

Maya |

PhD students, Andy and Ghislaine also spoke about their experience with audiobooks before the course and how they attempted to listen while working and driving, cleaning and crafting. They also found that they could not concentrate on what they were listening to when doing these other activities and mostly gave up on audio books. |

| (14:21) |

Andy |

I started listening to audio books. I got an audible membership to trial because I was working in a warehouse and so I had a lot of time moving my hands, but my brain was idle. So I remember I bought The Brothers Karamazov and I thought that that was gonna be the book and then honestly totally just distracted me. I never listened to audiobooks after that. I found it pretty unpleasant and I couldn’t focus. It was really hard for me to focus. Yeah, otherwise maybe driving. I drove cross country twice last year, so I definitely listened to some audio books, but, same thing, totally zoned out most of the time. |

| (15:01) |

Ghislaine |

Yeah, I have kind of a similar audible trial experience where it’s like, yeah, I’ll try this out. And I downloaded the entire works of Poe and I’m like, yeah, I can listen to this at night or whatever. And after maybe 5, 10 minutes, I couldn’t focus on it, I just fell asleep. So I [Ghislaine laughs] since then, didn’t try to listen to other audiobooks cuz it just didn’t hold my attention. |

| (15:29) |

Maya |

[Quite electronic music begins to play]

Even after the course, the students reported that their ability to multitask while listening almost entirely depended on the content of the audiobook and the nature of the task at hand. |

| (15:40) |

Ghislaine |

[Electronic music ends]

On your note, Ella, of listening to non-serious books after the class ended, and it was like winter break and I still had this Audible subscription that I had to renew [laughs] because of the class and I forgot to cancel it. So I’m like, you have one credit. So I got this very unserious book called The Housemaid and all through the break, well not all through because it just took me a couple of days, I listened to it nonstop and I had a really good time listening to it, doing menial tasks, like dishes and, you know, little crafts.

So not for sleep and not for any serious work and not serious books, I could see myself maybe getting into audio books now, but yeah, I don’t know. |

| (16:26) |

Ella |

Yeah, I mean I mostly listen to audio books if I’m walking or doing the dishes, like nothing that takes any more brain power than walking or doing the dishes. There’s a very fine line, like the harder the book, the more specific the task has to be to be like the right task to listen to an audiobook. |

| (16:42) |

Maya |

These conversations challenged the belief that listening is passive. Maia likewise spoke to her surprise at how much attention listening required and how this challenged her assumption about the primacy of the written. |

| (16:55) |

Maia |

I wasn’t anticipating, as you’ve said as well, the amount of attention or even treating the audio as an artifact in and of itself. I didn’t realize coming into this class that I thought about it as a secondary modality to like a written form, especially from my past experience of really struggling with the audiobook and more complex wordplay that didn’t really amplify the porosity of what I was reading at all. |

| (17:21) |

Maya |

And Jentery related that when he attempted to listen while doing chores, those chores often took a very long time. |

| (17:28) |

Jentery |

To use one of my everyday examples, I often listen to a podcast while I’m doing the dishes in the evening and it’s always striking to me that there’s something said or something I heard that I will stop and go take a note. I’ll write that down on my phone or I’ll have a notebook next to me and I’ll make a note of it to return to later cuz I’m worried I might forget it, perhaps, just due to age at this point, but I go and I make a note and then I go back and then all of a sudden I’ve been doing dishes for two hours. It’s such a…it’s almost ritual at this point. |

| (17:55) |

Maya |

For Jentery, careful listening did not necessarily lend itself to multitasking, or at least to efficient multitasking. Ella described how even though she had been listening to readings in other courses and thought she was prepared, the reality was very different when confronted with the kind of listening she was asked to do in her Concordia class with Jason. |

| (18:16) |

Ella |

I was sort of primed for the class. I was like, great, now it’s just official, I’m going to be listening instead of reading. But I guess some of the things that we ended up having to listen to for the course required a lot more attention than I usually gave to my listening. And so I’d have to sit and listen rather than walk or do the dishes and listen, which I find a lot more difficult. I don’t know, I lose track, I lose focus if I’m just sitting and listening. |

| (18:42) |

Maya |

Although we sometimes turn to an audio version of a book as a time-saving mechanism, thinking we can do chores when listening or as Maia says, “two birds, one stone”. It is not always possible. Often the listening or the chore or both are compromised. Further, we should bear in mind what Mark Kerrigan calls auditory fatigue; the analog to screen fatigue. Which he describes as experiencing a limit to listening, which is increasingly familiar, a sense of being oversaturated and unable to hear myself think.

[Electronic music begins to play]

In the conversation with Jentery, he talked about the challenges of asking people to take listening seriously and understanding the obstacles to attentive listening are part of that conversation. But to bring listening more fully into the classroom, we also need a better understanding of the processes of reading on the page. If listening is relentlessly and usually negatively compared to reading, we should first make sure we know what we mean by reading in the first place. |

| (19:46) |

AI Generated Voice |

Chapter three, what is reading anyway?

[Electronic music ends] |

| (19:52) |

Michelle |

I asked Jentery about how dismissals of listening are often informed by idealized notions of reading, particularly reading in print what you read.

[Audio from interview with Jentery begins]

But I wanna go back to what you said earlier about often listening while multitasking, and I guess that just strikes me as so interesting and important and I think it is one of the reasons why lots of us do listen to a lot of different things, but I guess what I’m wondering is can we again maybe muddy that and say listening doesn’t just have to be deep or intense or close, that sometimes we don’t listen with that kind of intensity and that’s okay.

So one thing that has come up with my students and I’ve heard this in the interview with Jason Camlot’s students, is that they kind of go in and out of attention. Certain audio texts are much easier to listen to, some are harder, but I also think that’s what we do when we read.

We just have this fantasy that when we read, we’re just wrapped and we’re reading every word, and we’re taking it all in. I think that waning of attention is common to both acts.

[Quiet string music begins to play]

[Interview audio ends]

Even though we often treat reading as if it is one thing, it is in fact a multitude of practices and cognitive experiences. Sometimes we read every word, but very often we scan or skim or surf when reading or simply fail to take in the words in front of us due to incomprehension or boredom or fatigue. And the same thing happens to us when we listen. Andy coined the phrase “ear skimming” to describe a similar experience that happens when listening.

[String music ends] |

| (21:22) |

Andy |

Yeah. That makes me think of skimming. When you skim readings that you’re not interested in, it’s like, listen, ear skimming [laughs], you kind of just blank out or, you know, distract yourself and then tune in when something picks up your interest. |

| (21:38) |

Michelle |

The contemporary neuroscience of reading as popularized by writers, including Maryanne Wolf and Stanislas Dehaene has shown us the complexity and variety of the neural processes that we designate by the single term reading.

[String music begins to play]

And notwithstanding the strong opinions about listening as compared to reading, there is a surprising lack of empirical research that directly evaluates how modality of presentation impacts comprehension and what little research there is has yielded conflicting results.

Naomi Baron’s 2021 book, How We Read Now: Strategic Choices for Print, Screen and Audio, surveys current research and reports that although some studies suggest that comprehension may be improved when texts are read on the page as opposed to heard, these studies are limited and other empirical evidence suggests no difference. Some research, for example, shows that with listening, multitasking and mind wandering may be more prevalent.

However, these effects appear to be lessened when what is being listened to is a narrative as opposed to an expository text. Some of the experiments involve listening to textbooks where depending on the subject matter, mind wandering is perhaps not surprising. My takeaway from her book is that the difficulties that are detected with oral comprehension and retention in some of the studies are more likely to be learned rather than innate. This interpretation aligns with research that shows that younger children are more effective listeners and that they lose these skills over time, becoming better readers than listeners.

Perhaps this is because younger children are rewarded for and taught to value listening and this capacity wanes as emphasis on reading written materials intensifies. At the college level, we need to ask whether students put the same mental investment and time into their listening as they do into their reading. Baron helpfully points out some of the specific ways in which audio texts, including podcast and audiobooks, can prove challenging in terms of comprehension and recall.

She notes that audiobooks often lack certain elements that appear in or are endemic to print and that have been proven to aid learning when reading written texts. Podcasts, she points out, usually present undifferentiated sound and emit what are called signalizing devices such as bold or metallics that emphasize what is particularly important, as well as other visual landmarks such as headings and page breaks that can help readers chunk material into more comprehensible pieces.

Audio texts also do not provide visual aids such as charts or graphs or images, all of which can enhance learning. Finally, annotation of written materials is a practice that has been proven to help readers understand and retain material, but annotation of audio can be more challenging. One of the reasons why the physical book has been such an enduring medium is because it enables annotation, whether in the form of handwritten notes, underlining or highlighting or adding sticky notes.

But performing any of these tasks with audio is, if not impossible, then less familiar, as our students are usually asked to speak or write about what they have read or heard. And as that is our work as scholars, we need mechanisms for marking audio to help us emphasize and find those passages we wish to return to. When listening to an audiobook or a podcast, we are often compelled to keep notes in a separate medium as Jentery did while listening by taking notes on his phone or notebook. This is one of the challenges we discussed.

[String music ends] |

| (25:12) |

Jentery |

Yeah, so the only audiobook I taught in that particular class was The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison. I recommended getting it in print as well, and I gathered probably somewhere between two thirds and three quarters the students did. So I did not, however, I demonstrated the use of annotation in the online class, like by showing how I annotate my own audio, you know, sharing a screen essentially, but I did not, and I should have, but I did not teach annotating audiobooks or annotating sound more generally.

In hindsight, if I had done it again, I would probably do something like that or figure out a way to integrate some kind of software or a mechanism to make it more approachable to students. But it kind of sparks my imagination here and I’m wondering how it is that when students were listening, how it is that they took notes and how that might correspond with and differ from how helped students take notes, say in the print novels that I teach, that would be a fascinating question. I’m sure people have studied this, but it’s not in my wheelhouse. |

| (26:06) |

Michelle |

Fortunately, annotation tools for audio do exist. Audible has a bookmark function that saves your place with a timestamp and in the digital file and allows you to enter notes. Tanya Clement, a scholar from the University of Texas, Austin, who is part of the SpokenWeb network, has been working with her team to create Audi Annotate: a web-based open source tool that supports audio and video markup.

These tools are needed to enable us to engage with audio in ways that are analogous to how we mark up text and print and now digitally audio annotation tools therefore seek to provide us with a set of options to approximate what we do with a printed book, such as turning down the corner of a page or adding a handwritten note.

Annotation can also support our spatial sense of where we are in a digital audio file, an aspect of reading that is normalized when we read a physical book, even if we don’t mark it up as we read, we tend to have a sense of what comes where, but this recall can be harder to replicate in an audio file. [Light electronic music begins]

Ella similarly reported needing to reference a print edition in order to anchor herself when listening.

[Electronic music ends] |

| (27:16) |

Ella |

So I ended up having to look at a print version just to anchor myself, you know, I’d look, oh, oh, this is like maybe a quarter of the way through the book, so it must be a quarter of the way through the audiobook. I mean, that was difficult, taking a long form audio piece and being like, somewhere in here I remember listening to a fun thing, now I gotta find where it is. So I would use the print for that, but then I was, again, just using like the free Gutenberg version of that. |

| (27:39) |

Michelle |

The printed book offers us navigational tools and opportunities for annotation that support the comprehension and retention of written texts, but they are not reading per se. As Ella points out, books can also provide images and other formatting and formal features that help us to make sense of the words on the page.

Audio is in need of tools that help us to anchor ourselves for the reasons mentioned and also because listening almost always takes longer than reading. I noticed that on the syllabus Jentery quantified the length of time students were expected to listen to the material he had assigned. [Light string music begins]

That was one of the aspects of teaching audiobooks that I struggled with as the audiobook of the novel, Milkman comes in at 14 hours, 11 minutes, and the two other audiobooks I assigned, Cersi by Madeline Miller and Girl, Woman, Other by Bernadine Evarist clock in at just over 12 and 11 hours, respectfully.

As we do not want to encourage our students to listen at faster speeds, and as we must acknowledge that re-listening may be needed, we must factor in the time it takes to listen, which is almost certainly longer than it takes to read on the page. Jentery explained that he had been quantifying expectations for how much prep time students would need to listen since the pandemic. [Electronic music ends] |

| (28:56) |

Jentery |

Since the pandemic, issues related like when, you know, your sense of place and your sense of campus changes, and the campus is kind of in your house now or in your domestic space. I think time management is affected pretty deeply and I gather research supports that assumption. So that was part of it, just making clear and or transparent labor expectations, while noting that mileage may vary.

But it also comes actually out of doing a lot of work with digital media and just more generally in digital studies, where in my own training and in my own education, I had gleaned a pretty concrete sense of how long it would take me to read a 200 page novel and I could assign that accordingly and we could talk about that in terms of time. |

| (29:38) |

Michelle |

What I hope these conversations have illuminated are the ways in which we as instructors can help our students. By recognizing that effectively reading written text encompasses a range of practices, we can think about how best to provide a set of comparable supports to enable our students to succeed in listening.

In the pedagogical audio we create, such as this very podcast episode, we can enact some of the signalizing devices that readers of printed material are accustomed to and rely on to make sense of what they’re reading, by adding section breaks, as I’ve endeavored to do in this podcast.

Although a podcast is in oral media, we can enhance it with visual aids and transcriptions as again is attempted in the blog post that accompanies this podcast. [Electronic string music begins to play]

One of the other immediate demands of teaching literary audio is providing students with a framework for understanding what they are hearing.

[Electronic music ends]

What is an audio book or a podcast anyway? A genre? A medium? According to Jentery, the critical conceptual category is format, and a podcast or an audiobook are both formats within the medium of audio. |

| (30:52) |

AI Generated Voice |

[Electronic music begins to play]

Chapter four: Format matters.

[Electronic music ends] |

| (30:58) |

Maya |

One of the most riveting exchanges with Jentery was about the conceptual categories he offered to his students to describe and distinguish between different forms of literary audio, from audiobooks to podcasts to radio dramas. Format occupies the zone between the more abstract category of media, on the one hand, and the more content specific category of genre, on the other. To break down the three conceptual categories, a familiar example may be useful.

[Electronic music begins to play]

Let’s take Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, which was first published in London in 1813 in three volumes. We begin with the most abstract category, that of media, which is usually divided into text, audio, video, and image. The medium of the novel’s first public appearance was text, but before its publication it lived in audio form as Austen is said to have read the novel aloud to her family in advance of publication. After its publication, it would’ve continued to be read aloud in countless homes across Britain and abroad, especially after its publication in Philadelphia In 1832.

In 1833, an illustrated version of the novel was first published, bringing the novel into a visual medium in 1940, just over 100 years later, it entered another medium; video. As we can see, a work like Pride and Prejudice exists in multiple media at the same time, and simply because it was first presented to the public as a text does not mean that that medium should necessarily have primacy.

The next conceptual layer is that of format, for example, within video there are different formats such as feature length film adaptations and mini-series, as well as many, many others. With the concept of format referring to how our particular media is structured and delivered. We may also create a typology of audio formats in which the novel has been presented, from the handful of amateur readings on Librivox to audiobooks narrated by celebrities.

The final conceptual category is that of genre, which describes content. Pride and Prejudice is a work of fiction, a novel, and we could historize it further by calling it a domestic novel or a comedy of manners.

[Electronic music ends]

In discussions with Jentery, he explained that with his students, he lent heavily into the concept of format, asking students to listen to a variety of audio formats, radio plays, serialized drama, voiceover narration, and first person video games. Using the concept of format to ground their understanding of what they were hearing, historically and technologically. |

| (33:35) |

Jentery |

I think one of the really useful aspects of that approach was that we could, in very kind of concrete ways and in palpable terms, talk about the ways in which audio achieves a context, if you will, and brings material together, brings together, for example, aspects of narrative and story with art and design. And since it’s so much about situation and context, you know, not taking for instance the kind of formalist approach to media where we kind of unmoor it from time and space and talk about it abstractly.

I think one of the consequences of that was we were also able to look at moments when this work was made and this work was produced. Actually look at the specificity of context in each case and talk about how format, genre, and audio production, just writ large is always kind of grounded in particular situations. |

| (34:28) |

Maya |

Throughout this podcast episode, we will return to one of Jentery’s key insights that thinking about literary audio through the lens of format helps us to situate it in place and time and allows, as he puts it, for audio to achieve a context.

[Electronic string music begins to play]

With all of these efforts needed to support listeners, it might reasonably be asked whether listening is worth it? If we need to provide new media frameworks for students, if listening requires as much, if not more attention than reading on the page, if it takes longer than reading a physical book, if it can induce auditory fatigue, and if in order to write about it, you still need special tools to annotate or a print version anyway, why bother?

Avid listeners of audio books, however, answer this question by noting that they often listen to books that they have already read in physical form, and yet always they hear something that they didn’t see. What are some of the ways in which listening enhances comprehension and enjoyment? What do we hear that we did not see and what questions or insights does listening give rise to that we would not otherwise have from reading the book in written form? |

| (35:40) |

AI Generated Voice |

Chapter five: Hearing What We Cannot See.

[Electronic music ends] |

| (35:45) |

Michelle |

Matthew Rubery, author of the foundational history of audio literature, The Untold Story of the Talking Book speaks to the different perceptions that come from listening and reading on the page. [String music begins to play]

Nearly all readers, he writes, report understanding identical texts differently in spoken and silent formats as various elements stand out depending on the mode of reception. He notes that the narrator who performs the story can be especially useful in giving voice to unfamiliar accents, dialects or languages. The vocalization of such distinctively oral text would otherwise be impoverished for many readers poorly equipped to sound out the linguistic effects for themselves.

An audiobook is a performance, an interpretation of the original text, often accentuated with the narrator adopting different voices for different characters and enhanced with sound effects and music, all of which bring the audiobook closer to theater or film even when it offers absolute fidelity to the written text, as is the case with most unabridged audiobooks. Jentery and I explored the performative aspects of the audiobook he assigned, Toni Morrison’s reading of The Bluest Eye. I asked him whether he attempted with his students to disambiguate the text as written from the text as performed by Morrison. |

| (37:07) |

Jentery |

And that, so we tried just that and actually I think it was a bit of a setup because when we went through and listened to it, and in many cases read alongside what we were listening, we did our best to think about the various roles, if you will, that Toni Morrison is playing in that audiobook of The Bluest Eye. So Morrison as author, Morrison as narrator, as reader, as voice actress, even as character voices.

And we went through and tried to mark how we would understand that differently. So I remember this exercise and yeah, and ultimately probably without a shock, we determined it was very obviously difficult to make a clean demarcation between one and the other when it would happen in a sentence and whatnot. |

| (37:48) |

Michelle |

As Jentery explains, there are many different rules that Morrison takes on in reading her novel aloud. Rubery distinguishes between different models of audiobook performances. The narration may be read by the author, by a professional voice actor, by a celebrity, or even by an amateur. Characters may be voiced by the narrator, sometimes in different voices or different actors may be cast to play different roles.

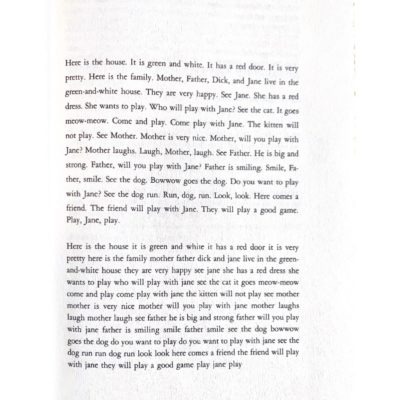

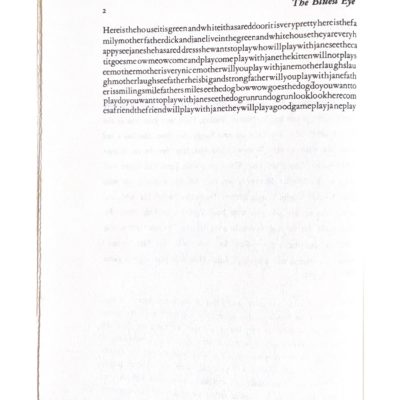

An extreme example of this is the audiobook version of George Saunders, Lincoln in the Bardo, which is performed by over 160 actors. Toni Morrison reads The Bluest Eye herself, performing the third person narration and also giving voice to different characters in the novel. Morrison also narrates another book that is embedded in the novel, one of the Dick and Jane Reading Primers, a series intended to help new readers first published in America in the 1930s.

These primers, with their idealized characters living seemingly problem-free lives, are white and middle class, setting up a potent contrast with the character’s Morrison depicts in her novel. Morrison’s novel begins with a Dick and Jane story of about 150 words. The Dick and Jane story is reprinted at the very beginning of the novel and it appears in its entirety three times, each time with different typographical features.

[Electronic music begins to play]

The first time the story is printed, there are spaces between the lines and the words, and the story takes up most of a page. The second time the spacing between lines and words is reduced, shrinking the presentation of the story to half a page with all punctuation removed. The third time the story is printed, all spaces between the words have disappeared with each word bleeding into the next.

To help you visualize this, please refer to the blog post for this episode on the SpokenWeb website, which includes images taken from these two first pages of the novel. Morrison’s repetition of the story three times in printed form seems to mimic a young child becoming proficient in reading, from one who slowly sounds out each word to one who becomes so fluent that she can run each word into the next, but the blurring of words into one undifferentiated mass has other implications.

As Morrison reads the three versions of the story in the audiobook, she speeds up the pace of her reading as might be expected, but a more sinister element also presents itself. Here is Morrison reading the first part of the story at three different speeds.

[Electronic music ends] |

| (40:22) |

Toni Morrison reading from The Bluest Eye |

[Morrison reads the text slowly]

Here’s the house. It is green and white. It has a red door. It is very pretty. Here is the family, mother, father, Dick and Jane, live in the green and white house. They’re very happy. See Jane. She has a red dress she wants to play. Who will play with Jane? See the cat? It goes meow, meow. Come and play. Come play with Jane.

[Morrison reads the text again, faster this time] Here is the house, it is green and white. It has a red door. It is very pretty. Here is the family, mother, father, Dick and Jane, live in the green and white house. They are very happy. See Jane. She has a red dress she wants to play. Who will play with Jane? See the cat? It goes meow, meow. Come and play. Come play with Jane.

[Morrison reads the text even faster]

Here’s the house. Green and white. It has a red door. It is very pretty. Here is the family, mother, father, Dick and Jane, live in the green and white house. They are very happy. See Jane. She has a red dress she wants to play. Who will play with Jane? See the cat? It goes meow, meow. Come and play. Come and play with Jane. |

| (41:46) |

Michelle |

[String music begins to play]

What Morrison’s voicing brings to life is both how the child learns to read, but also how through the rote rehearsal of the story at a speed that renders it mostly unintelligible the white family living in the green and white House becomes internalized as the norm and the ideal.

In the forward to the printed version, which interestingly becomes an author’s note at the end of the audiobook, Morrison reports that the story originated in a conversation with a friend from elementary school who confided in Morrison that she wished for blue eyes. [Electronic music ends]

Within the first four minutes of the audiobook, Morrison’s pointed reading of the Dick and Jane story at three different tempos draws out the menace lurking within these stories for Black children; the Dick and Jane stories provide just one potential explanation for a central question the novel poses: How does Morrison’s childhood friend and the character in the novel who asks for the same thing, learn to wish for the bluest eye? What Morrison describes as racial self-loathing.

For me, the meaning of Morrison’s rendering of the Dick and Jane story in the print novel is enhanced by her performance of them. I might have had an inkling of her meaning by reading it on the page, but it is amplified by her reading as seeing and hearing her translation of the embedded story intensifies and crystallizes her meaning.

At the same time, any attempt to read authorial intention into the audiobook performance must be interrogated. To return to Jentery’s suggestion that by listening and situating the audio recording within the time and place of its production, audio achieves a context. We might want to ask students to reflect on the fact that Morrison is reading the novel in 2011, more than 40 years after its first publication in 1970. Morrison also makes changes to the presentation of her peratext, moving, as I said, the forward from its position prefacing the printed novel to the end when she reads the novel for the audiobook.

The reason for this shift seems likely to do with the difference in media and format. Readers can and often do skip preparatory material in print, but this action of skipping ahead is perhaps less natural with an audiobook. Beyond these changes, what does seem consistent over this 40 year period is Morrison’s belief that her books were meant to be heard.

Thus, she describes the language she uses in the novel as speakerly, oral, colloquial. And it is perhaps for this reason that her audiobooks are so powerful. Indeed, Morrison performed all of her books as audiobooks, demonstrating her investment in aurality. Sarah Kozloff has argued that audiobooks create a stronger bond than printed books between storyteller and listener by invoicing the narrator, and many listeners in particular enjoy hearing authors perform their own works.

Audiobooks, particularly when read by the author, seem to bring us closer to the source of the words and the story, much in the same way a handwritten manuscript seems to bring us in proximity to the hand and body that inscribed it. Jentery related to me how he found it effective, as he put it, to bring the author into the room in assigning an audiobook read by the author like Morrison’s Bluest Eye and by playing interviews with or speeches by authors. |

| (45:03) |

Jentery |

Well in American fiction courses, I love including videos of James Baldwin’s speeches in a lot of material. I think that’s fascinating to bring the author into the room and I often when I’m teaching primary source, a novel for example, love to include and play in the class podcast interviews with those authors, in a way that allows students to think about the kind of context around the book, but also just kind of what went into the book and some of the motivations for it. |

| (45:29) |

Michelle |

Jentery and I discussed how changes in digital technology make it much easier too, as he put it, bring the author into our classrooms. We have a wealth of freely available audio and video such as the New Yorker Fiction podcast, which makes hundreds of stories from the magazine’s archive and current issues available to listen to, some enhanced by extended conversations about the stories.

In addition to improved access to primary source audio material, Jentery also points to how changes in accessibility to technology and equipment for playing and recording audio are transforming what is now pedagogically possible.

[Electronic music begins to play]

The final section of this episode considers how technological developments have changed both what we and our students can do with audio. |

| (46:22) |

AI Generated Voice |

Chapter Six: Teaching with Audio Now.

[Electronic music ends] |

| (46:28) |

Maya |

In the conversation with Jentery, he reflected on how much has changed in just the past decade of teaching audio. |

| (46:35) |

Jentery |

When I was teaching sound studies at the University of Washington and the University of Victoria between like 2010 and 2012, the accessibility of material there, like what I could circulate and what I couldn’t, what I had just to play, say, on a desktop computer in the classroom, but also what students could record and what with, I’m always careful not to assume that students have access to technologies and computers.

But I can say just matter of factly, the degree to which they would need to, say, rent or go to the library to acquire an audio recorder has dramatically changed, just given the ubiquity of mobile phones at this point. So there’s that angle, which recording is, I think, on the whole, it’s not universally accessible, but it’s more accessible to students now than it was then. I think just being able to hit “record” is more ready to hand. |

| (47:17) |

Maya |

Recording equipment and podcasting software also open new forms of assessments. As Jentery explains, when working with sound, it often makes sense to sample the sounds being analyzed and hence an audio essay is often the best way for a student to fully engage with the material. |

| (47:35) |

Jentery |

A thing that really struck me as compelling and did gain traction among students in the seminar was the idea of composing in such a way, composing an essay, an audio essay if you prefer a podcast, in such a way that makes room for your primary sources to speak and to be dialogic in that sense. So, the inclusion of samples of authors reading their work, of hearing the author’s voice in a way that I think, again, you don’t need to adhere to a metaphysics of presence to find this interesting.

You can just think of it in terms of honoring other people’s work and what it means for you to hear other people’s work in your writing and your composition in the production of space and time. And so I liked that too, the threading through other people’s work into your material in a way that might be a little different than reading a block quote or seeing an image on the page. |

| (48:22) |

Maya |

Jason Camlot’s student Ella explained that she chose the podcast format for her final assessment because it seemed more natural and easier than writing and attempting to describe her object of study, which were recordings of poetry readings. |

| (48:37) |

Ella |

I chose to do the long form. I mean, I simplified in my head the long form. I told myself I’m not gonna do interviews or anything, I’m just going to essentially record myself reading this essay and then insert the sounds I’m talking about because I think this might actually be easier than trying to transcribe those sounds in a way that I can then analyze them in writing.

In this case, I could just play the sound for you and you can hear it and then I can talk about my thoughts on it. That seemed like an easier process, actually, because I was going to be working with a bunch of different old recordings and newer recordings and poetry readings and stuff and, it just, I don’t even know how I would’ve approached describing some of this, especially cuz I was working, for instance, with experimental poetry from the eighties and I was working with really old recordings on wax cylinder of Tennyson and like, how do you describe those kinds of experimental or super old degraded sounds to people in order to then really get into a conversation about it? So it just made sense to have people hear them. |

| (49:36) |

Maya |

[Soft electronic music begins to pla]

Ella’s observations about the need to incorporate the different sounds she was working with,once again return us to Jentery’s idea of audio achieving a context.

In order to describe and situate 19th century wax cylinder recordings within their particular historical and technological moment, it is necessary to hear them in the same way that we say a picture is worth a thousand words. A short audio clip, here, the Tennyson recording on wax cylinder that Ella refers to is likewise easier to understand when heard.

[An audio clip of Tennyson reading poetry plays]

In addition, Ella explained her preference for the audio essay format by echoing Jentery’s sense that there might be something more dialogic and open about it. |

| (50:32) |

Ella |

I do think it was faster for me to write for this podcast than it was for me to write what could have been a conference paper because I don’t like the structure of the academic paper where you say your thesis statement in the beginning, prove your thesis statement, and then restate your thesis statement. I prefer a structure where you sort of go from a starting point, like essentially more of like a thought process, like, here’s my starting point and by the end of it you’re like, here’s where I got from that starting point.

I had the option to do that with the podcast. Whereas usually when you’re writing an academic paper for a class, they don’t give you the option to just run with things. So it just went a lot faster cuz it was a form that made more sense to me. |

| (51:11) |

Maya |

Jentery also spoke about how crafting an audio essay is different than writing for the page and reading it aloud, or even reading a conference paper, which might be designed for oral delivery. An audio essay perhaps because it is modeled on the podcast may be more audience oriented. Maia reflected that having the opportunity to listen to each other’s podcast or audio essay assignment distinguished the course from others she had taken where a student’s writing is primarily directed towards the professor. |

| (51:38) |

Maia (51:38) |

It was also interesting to hear everyone else’s podcasts because in a normal normal class in, a more traditionally like written assignment based class, you don’t read everyone’s essays and get to interact with your classmates like that. And I think, for me, it was a really interesting atmosphere that I don’t know that I’ll ever have again. It was really, really special in the way that we all interacted and I don’t know to what part of that was the sharing in a medium that is more shared, listening of togetherness rather than kind of an individualized personalized reading. |

| (52:13) |

Maya |

For Andy and Ghislaine, the audio essay felt different than in-class presentations, which are to a great extent formalized. By contrast, the audio assignments were diverse, fresh, and engaging. |

| (52:27) |

Andy |

Everyone took it in such a different direction. So it was like when you have a presentation, I feel often they follow a similar format and structure, but with this it was completely different in every kind of way. Genres across the board, like kind of there were no limits of what you could really do and I think that’s what for me made it different than just a typical class presentation. [String music begins to play] |

| (52:51) |

Ghislaine |

Right, that makes sense. So it’s like with regular normal class presentations, it would have been as if, you know, someone came in singing and dancing versus, you know, just with their PowerPoint. [laughs] |

| (53:03) |

Maya |

We will end with Ghislaine’s words, as her comments should inspire both instructors and students to turn to literary audio, both as a source of teaching material and as a form for student work. We believe she speaks to what we all could use in our classrooms. A little more singing and dancing and a little less PowerPoint.

You have been listening to “Audiobooks In the Classroom”, a SpokenWeb podcast episode by Michelle Levy and narrated by Michelle Levy and Maya Schwartz. Thanks for listening.

[Electronic music ends] |

| (53:54) |

Katherine McLeod |

[SpokenWeb theme music begins to play]

The SpokenWeb podcast is a monthly podcast produced by the SpokenWeb team as part of distributing the audio collected from and created using Canadian literary archival recordings found at universities across Canada.

Our producers this month are Dr. Michelle Levy and MA student Maya Schwartz, both based at Simon Fraser University. Our supervising producer is Kate Moffatt. Our sound designer is Miranda Eastwood, and our transcription is done by Zoe Mix.

To find out more about SpokenWeb, visit spokenweb.ca, subscribe to the SpokenWeb podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you may listen. If you love us, let us know. Rate us and leave a comment on Apple Podcasts or say hi on our social media @SpokenWebCanada. Stay tuned to your podcast feed later this month for ShortCuts with me, Katherine McLeod. Short stories about how literature sounds.

[SpokenWeb theme music ends] |